Fearful behaviour is another really thorny, long-term issue that many adoptants struggle with, particularly if your new rescue is completely shut down. In many ways, like separation anxiety, it is one of the most distressing behaviours that your dog can suffer from. Often, it can be tied up with aggression or reactivity around humans or other animals. It can manifest in escape behaviour, confinement phobia, destructive behaviour or isolation distress, and is not easily managed. What is worse is that many of us share a desperate desire to do something, anything, to help these dogs overcome their fearfulness, and we can often make it worse.

There are many reasons why a dog is fearful or less resilient than another. Patricia McConnell gave a talk recently for the ASPCA about resilience in dogs, and she talks of their ceiling or upper limits for resilience on a scale of 1 – 10. I think the same is true for fearful dogs, too. There is a limit to which our fearful dogs can bounce back, and I think that is often hard for owners to accept.

Sometimes that number on the scale is driven by genetics. Often it is a result of breeding. Some breeds are naturally more timid than others. It is unusual to get a shut-down beagle for instance, or a wire-haired fox terrier, but not out of the realms of possibility. But to get a scared or shut-down griffon or hound come through our gates is no rarity. And it is not that much about experience. Anglo-Français hounds, for instance, live in much the same conditions for the same purposes as an Ariègeois hound, but it is unusual to get a very timid Poitevin or Anglo, and incredibly usual to get a timid Ariègeois. Maybe we just get the gunshy ones and the rejects, though. I can’t say for sure. But where some breeds have the potential for a 10 out of 10 potential for confidence and extroversion, some dogs have perhaps a potential for a 6 or 7.

Sometimes it’s a result of parenting or family lines within a breed. Timid canine parents give rise to timid canine babies. They can be unusually fearful of new experiences within the breed. Accidental or thoughtless breeding can result in adult dogs who will never reach more than a 4 or 5 on that scale. Very, very occasionally, that may even be as limited as a 2 or a 3. For seven spaniels who came to the refuge over two years ago and who have now all been adopted, for the whole family, their chance to recover from fear or to cope with new experiences is perhaps a maximum of 5 for one or two. For two of them, one year on after their adoption, to think they might be a 2.5 out of 10 one day is as high an expectation as we could ever have.

It can also be pre-natal experience, in utero. Cortisol, the stress hormone, has the potential to cross the placental barrier if the mother experiences particularly high levels of it. Thus the puppies are born into a world that their bodies are already telling them is stressful or traumatic. Stressed mothers give rise to stressed offspring, and it’s not always a learned behaviour. Resistence to stress and resilience after a stressful event is very much determined by breed, familial lines and events during pregnancy. Those things in themselves can dictate whether a dog will be a 4 or a 10 on that scale.

Of course, it doesn’t stop there. As soon as a puppy’s eyes open around 2 – 3 weeks, it is no longer cossetted in the comfort of a senseless existence. Their window for socialisation is long – much longer than it is for many wild predators, and certainly much longer than it is for species who serve as prey to predators. But even so, if we don’t prepare our puppies for life by the time they are 13 weeks old, we are only ever to undertake remedial socialisation.

After even 6 weeks, a puppy is much less open to experience than it had been at 5 or 4 weeks. One fearful trip in the car around 6 – 8 weeks can lead to a lifetime’s fear of cars. Then there are secondary fear periods throughout juvenile and adolescent periods that may affect a young dog too. One-off events in adolescence can make a big impact.

By the time, then, that you pick up an adult rescue dog, nature and nurture have done a good job of determinining whether you’re getting a dog who is fairly bomb-proof, or whether you’re getting a dog who is destined to go through life finding much of it the equivalent of living in a war-zone. The reason your dog is fearful is often nothing to do with abuse or neglect.

As with everything, a trip to the vet is part and parcel of eliminating medical reasons for fearfulness. Fear of being handled can be a reaction to pain. If a dog steers clear of you, they could have pains you just don’t know about yet. Deafness or hearing problems can also be an issue. Storm phobia or sensitivity to the weather is another type of issue that can have issues later: dogs who are storm phobic are more likely to suffer hearing loss in later life. Whether there is a link or whether it is just a surprising correlation isn’t known yet, but finding out your storm phobic dog has an inner ear infection that can be cleared up through a course of anti-biotics is much easier than dealing with his storm phobia. Of course, fearful dogs can be incredibly afraid of the vets, so many owners avoid taking them and miss out on a medical diagnosis that could be easily dealt with. Hypothyroidism and many other medical complaints can lead to behavioural changes. This is especially important if you have lived a long time with a dog who has become or is becoming fearful rather than a dog who has always been fearful.

The first step in overcoming fearfulness in a dog is knowing that you may need to adjust your expectations of what your dog will ever achieve in terms of confidence. It may never, ever be possible for your dog to find car rides to a busy day at the beach something wonderful or joyous. For some dogs, two hours in the car followed by ten hours on the beach surrounded by kites and tides, deckchairs and barbecues, screaming children, ice-cream vans and other dogs may never, ever be possible. A ten-minute ride in the car to a quiet lake with one or two people in the distance and a few quiet yachts out on the water may be the most your dog will ever cope with. And you may not ever get them to find that as pleasurable as you do.

The first thing you have to do then is ask if your expectations are humane? Is it kind to the dog to want to take them to a busy fairground? Is it kind to even ask them to find a fairly quiet park to be something of pleasure?

You also may have to adjust your timescale as to when you might expect progress. And you may have to factor in setbacks too. For some, overcoming fear can be a lifelong journey.

You may also have to do a lot of management and anticipation. For some dogs, a home may be a confining prison full of strange noises and bizarre contraptions like garbage disposal or refrigerators humming. Even the wires in your walls and your lights make sounds that can be terrifyingly incomprehensible to a dog. What you also cannot do is ever contemplate punishment or negativity, even if they become aggressive in the face of fear. Yesterday, when grooming a dog who seemed to be very much enjoying it, his eyes flickered. He moved away and growled, showing his teeth. The only time I have ever seen a dog do this has been when it has been safely on a lead or behind a fence when I could get away, or between dogs when it has escalated into a full-on attack if there wasn’t some substantial giving way. This one was blocking my escape. Something set him off – fear of being touched maybe, despite how much he’d been enjoying it – and despite how utterly terrifying it was, I was stuck. The only tool I had in my toolbox was my own body language. I froze. Two minutes, I was trapped there with a dog who was frozen too, eyeing me in case I moved, a dog with a bite history. When fear and aggression come together, it can be the most dangerous of situations. So you have to think of your own safety. If your dog is fearful of touch, confinement or restraint, grooming, handling or manipulation, make sure you always have an escape plan. Not every dog will shut down when afraid. Some will come out fighting. If you are in any way trying to deal with a fearful dog with methods to make them submit, be prepared for it to fail and it to risk both the dog’s life and your own. Now is not the time at all to subscribe to hierarchy and pecking order schools of thought. It is also not the time to ‘flood’ your dog by over-exposing them to the objects of their fear in a hope that they will ‘get over it’. This will almost certainly also lead to a shut-down dog or a dog who fights back.

For many dogs, being “shut down” is a learned response to stress. In human terms, we call this ‘learned helplessness’.

Many will no doubt accuse me of anthropomorphism. Seligman’s experiments about depression and stress in the 1960s were, however, performed on dogs.

What did he learn? That dogs who had faced inescapable trauma in the past could not see a way out, even when one was provided.

He said, for humans, that the best way to help them out of learned helplessness, was to help them find the exits, metaphorically speaking.

The same is true for dogs. We have to teach them how to cope again.

For humans, this is easier. We have talking therapies, hypnotherapy, cognitive therapies, group therapies, medications. We have psychiatrists, psychologists, counsellors, therapists. An enormous amount of funding is dedicated to helping us be resilient. We can learn to cope with trauma and become resilient once again. Despite all that, there are a lot of people who still have unresolved problems or fears. But if you’ve ever found yourself backing out of a friendship or relationship because the person ‘needed therapy’ or ‘had baggage’, then imagine this for dogs, who have no use for ‘human’ therapies at all.

So how do we teach them how to cope and find those exits from trauma or stress?

The first is by managing the environment in which the dog lives. Change and household disruption is challenging enough with a resilient dog, and can be almost impossible for a fearful dog. A household filled with lively, unpredictable children is also not a home for a dog who needs a lot of behavioural change. Regular routines, including mealtimes and bedtimes will be vital. Quiet homes away from major roads and away from a lot of external stimuli will also be a real bonus. Fearful dogs are more likely to try to escape if something startles them, so a secure garden is a must. That may well include netting over the top – when you’ve seen dogs scale 3m fences, or jump and clear 2m ones, you realise how nothing short of a total prison may be required just to keep them safe.

Needless to say, never let a fearful dog off the lead until you are 100% sure that they are unlikely to have a flight response (or fight) response and that you have a good six month period where you’ve not had a fearful response to anything on a walk. Anything less and you are risking the dog bolting for good. It is impossibly hard to catch fearful dogs, who then evade capture like a professional. Sadly, most fearful dogs who get out are never recaptured and we can only assume the worst.

A house may also in itself be difficult for a fearful dog to cope with, especially if they have never lived in a house before. Sometimes, the kindest thing to do is give them an indoor garage space with a dog flap into a secure, concreted outdoor yard space, and gradually introduce them to the house at their own pace.

Many fearful dogs may also have never known humans. Cutting them off from their own kind can leave them as autistic strangers who have nothing in common with their new life and no way to understand or communicate with the creatures around them. A confident dog can be the making of a fearful dog. To see how Jazzy, a fearful setter, came on leaps and bounds with Isaac was to watch a miracle happen. This is not always the case, but consider carefully about whether the fearful dog you plan on adopting or you have already in your home is a dog who only speaks ‘canine’ and finds it easier to be with others of his kind. Although little study has been done on how dogs learn from other dogs, dogs can and do learn from the others around them, just not as often as we’d like. If being with a confident dog was a ‘fix’ for fearfulness, it would make it very easy indeed. But it is a factor to consider. Certainly for dogs who suffer from isolation distress, other animals are a must. Just remember that learning goes both ways.

It is not enough, then, to simply want to save a fearful dog, to have noble intentions.

You have to have the right home for them, otherwise your struggle is going to be an uphill one.

You also will make more progress if you are conscious of your own body language around dogs. Turid Rugaas’s excellent book On Talking Terms with Dogs: Calming Signals can help you learn how to move around your dog in ways that are not threatening or scary for your dog. For instance, few people realise how a direct stare or eye contact can be very rude and ill-mannered between dogs, yet we expect our dogs to stare dotingly into our eyes. Your attempts to look into the soul of your fearful dog could be making them think you have aggressive intentions. Tips like not looking directly at the dog, making very small movements, turning your back on the dog (if you trust them not to attack), turning your head away from them, or crouching or sitting on the floor can show them that your intentions are positive. It is vital to let a fearful dog approach you, and not the other way around, forcing the reaction. When you have a positive relationship with your dog and they trust you, progress will be much easier.

You can’t establish trust with a dog, though, if you keep forcing them to do uncomfortable things.

When you have managed your environment, so that it is as stress-free as possible for recovery, and you have also managed your own behaviour, you can then also start to write a list of your dog’s triggers – the things that set them off. For a fearful dog, you have to think about all the senses: sights, sounds, smells, sensations. That can be touch. It can be even things like a gust of wind. Whilst you may not be aware of the effect of your wind chimes or the buzz of a fluorescent light, these can be precisely the things that make it hard for your dog to settle. Then other things like thunderstorms, cars passing, sirens, low-flying planes. Even insects can be difficult for some animals to cope with if they have been stung in the past. You want a list of every single thing that sets your dog off on a fearful pathway. That can be people. Once you know it’s people, you can start to work out what type of people. It’s common for dogs to be afraid of men, though this is not usually an abuse reaction. Men have harder faces, more facial hair and are often taller and more purposeful in their actions than women. It could just be one of those things.

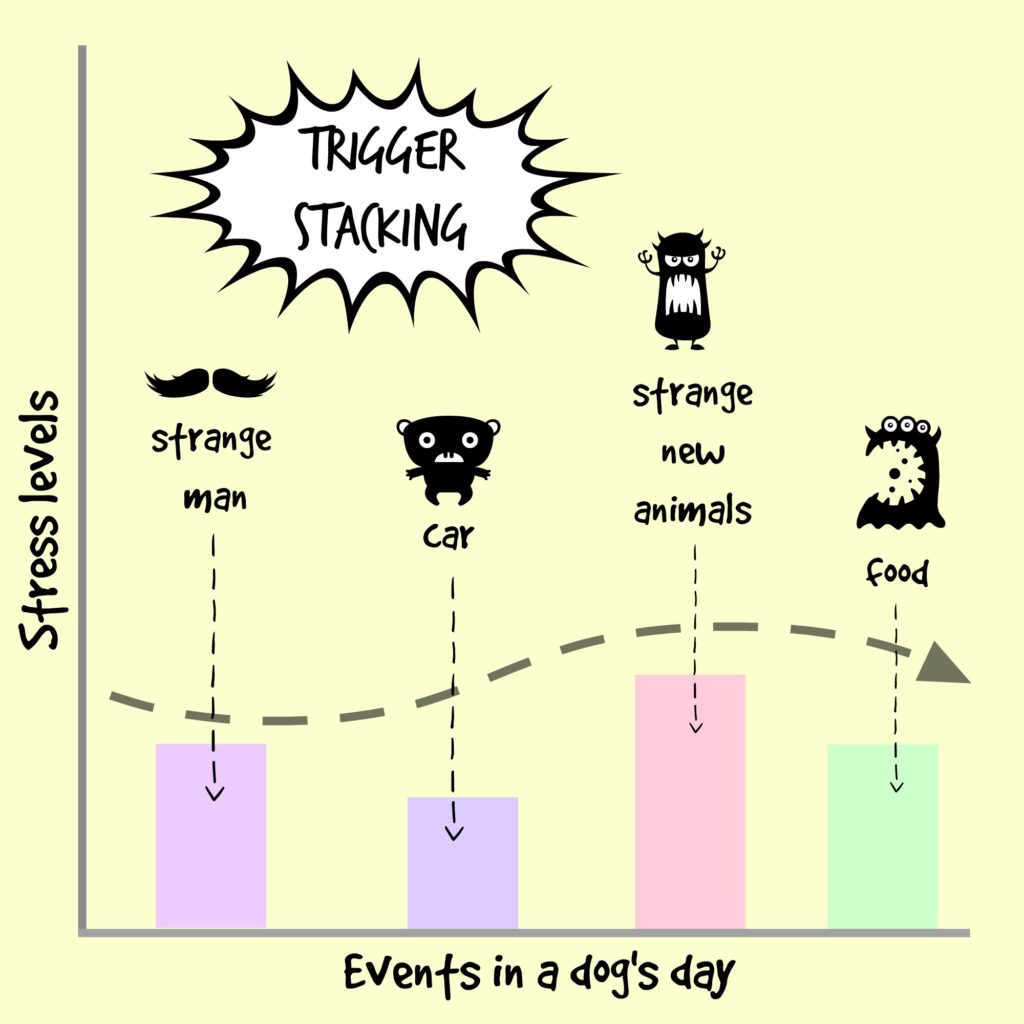

For triggers, you may well find that your dog can cope with one or two, but when the triggers come together, it can cause fearful responses.

Normally, our responses to triggers means that we have a recovery period between, where our adrenaline pathway returns to normal and our body adapts to the stressor.

When we start down the stress response pathway, adrenaline is produced to help us run or fight. Cortisol is also produced. This is important and we’ll come back to it later. Normal responses to stress include avoidance (not looking at it, backing off, seeking shelter) defense aggression (growling, snapping, barking) looking for contact with humans or other animals for reassurance (hiding between your legs, often!) seeking attention from a bonded human or animal. When dogs can’t escape or attack, you will see other behaviours too. Lip-licking, flat ears, tense faces, panting, low body posture, seeking escape, slow movements. They’ll be reluctant to take a treat (which has implications for positive training and counter conditioning to overcome the response)

Normally, the trigger goes away and the situation returns to normal. The body stops making stress hormones and within 70-110 minutes, most of those hormones have dissipated. The dog learns to tolerate these small events and episodes. Cats in the garden, postal workers, teams of cyclists going past… they’re strange and unfamiliar events and your dog will have periods between them to recover.

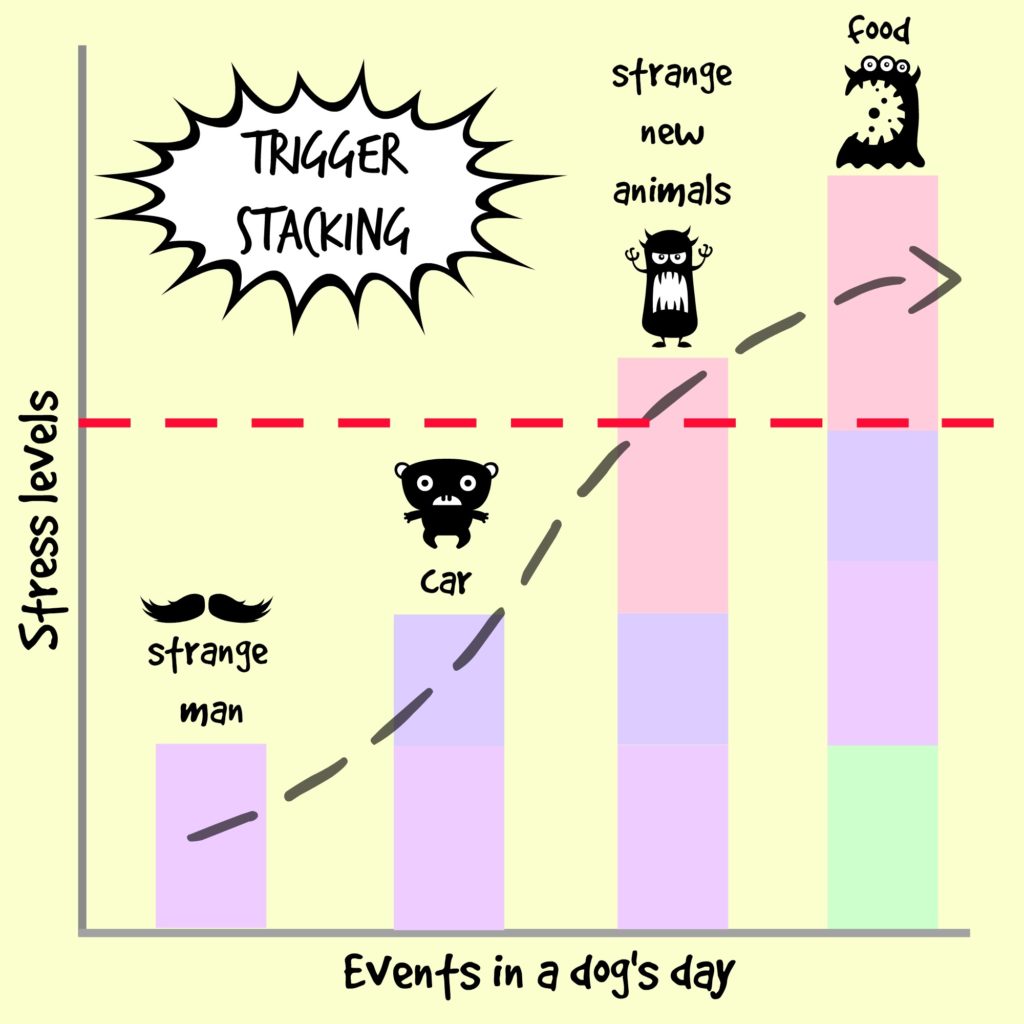

But when a fearful dog lives in a state of constant stress, those triggers stack up.

You know this very well if you’re a regular Woof Like To Meeter.

At this point, not only does the adrenaline not subside, but the cortisol in a dog’s system has no chance to subside either. Where adrenaline is used up quickly in the fight-or-flight response, cortisol, the stress hormone, is not. It takes much longer, sometimes as long as two weeks between fear reactions.

This is when it’s time for a ‘cortisol vacation’ or a ‘cortisol break’ – a period of time where your dog has as few triggers as possible. Usually, this means no walks and no over-stimulation. No ball play or energetic play (which also sets off an adrenaline response) and absolutely zero triggers. This might be two weeks, or it might be a month or two. Only your dog can tell you.

That means too that you’ll need to find other ways to engage and entertain your dog so that their system has a chance to purge itself of cortisol. There are plenty of ways you can keep your dog’s mind going when you are having a break from walks or stressful environments: Real Dog Yoga, mental games, brain games for dogs and Sprinkles are just four ways. This can be tough to manage in a multi-dog pack if you walk together, but I generally find the collective energy of group walks for dogs to be incredibly over-arousing, not a good way to let off steam at all. It takes a bit of getting around, but see if even a 48-hour break makes a difference? 48 hours without walks won’t do your other dogs any harm and could begin to break a pattern of over-arousal in the home.

You can also use this time to build in other trust-building exercises like “Look at Me” where you reward your dog for moving towards you. Reinforcing basic obedience like ‘sit’ and ‘stay’ can also help. Touch-targeting, hand-targeting and eye contact are also teachable things that you can do instead of dragging your dog out for a walk that may well be the equivalent of an hour in a warzone to your dog.

A cortisol break is not a long-term solution for your dog. It is exactly what it says it is: an opportunity to recover from elevated levels of cortisol. Your aim is not to cosset your dog from the world in the long term but to give them the equivalent of a hormonal spa break. You can reintroduce the walks and their various triggers when your dog is showing you that it feels comfortable.

A good way to do this is a game called “Ask the dog”. When a dog who has been trained to stop and check back with you does exactly that, it’s a good time to check if they are comfortable going forward. Take one step forward and see if your dog is happy to come with you. If they are, things are good. This is a great game for any dog who is hesitant or nervous. I start by dropping a treat on the floor about two metres away, then rewarding the dog for looking at me. I move, reward the dog for moving towards me or looking at me by saying “Yes” once I’ve made sure the dog knows this word is a cue for a treat, and then I drop another on the floor. Every time the dog looks up and moves in, I say yes and drop the treat on the floor. You can see Leslie McDevitt explaining about Pattern Games here

You can see Leslie modelling the Up and Down game at 3.00, which is another thing you can teach a fearful dog during a cortisol break instead of going for a walk. This works also with fear-aggressive dogs too. It’s a great game for establishing trust with your dog and keeping the focus on you. Your fearful dog must be able to trust you and look to you, and food is an amazing way to do that.

There are many, many stages in dealing with fearful behaviour and establishing trust in you is the toughest step. A dog that backs away from you or won’t come to you is a dog that needs to start right at the beginning, learning to be around you and learning to relax. This is where you absolutely need to let your dog make the choices about coming to you. It is not something you can force or coerce. If you are having problems with a dog who constantly backs away from you and cannot be caught, this is a good time to seek out a positive trainer who can help you change that response. Approaching you is step number one for many dogs.

Being handled by you is often step number two. Many dogs are afraid of being handled. Our hands and arms move fast. We grab first and think later. That can be very scary to a dog. Teaching them that your hand coming towards them means good things can also help them establish trust in you. Collar grabs are another important thing to teach a fearful dog. Once your dog accepts handling, you can build in TTouch or canine massage to help your dog relax even more around you. That is a huge step forward for many fearful dogs.

When you have a dog who accepts touch, you can also teach them a chin target or Chirag Patel’s “The Bucket Game” both of which allow a dog to communicate with you that they are feeling uncomfortable long before they get to the flight-or-flight response. You can see Emily Larlham teaching a calming chin touch here.

Since this is a behaviour that the dog offers, they only offer it when they feel comfortable.

Keeping your dog calm and avoiding the biological stress pathways is the best and most reliable way to overcome fearfulness. A gradual reintroduction to triggers one step at a time is vital.

With that in mind, the next post will look at how to help your dog overcome his arousal around a trigger. That might be something he is fearful of, or something he is reactive to, or even something he is aggressive around.

I also can’t recommend highly enough Debbie Jacobs’ book, A Guide to Living With and Training Fearful Dogs and her website, Fearful Dogs.

You may never, ever have a 6 or a 7 out of 10 where it comes to your dog’s confidence levels and resilience, but there is magic in moving a dog who is a 2 out of 10 to being a 2.5 and a 3 or a 4. It is all progress, no matter how slow. Some dogs, particularly street dogs, seem to come to a moment where they kind of shake off their anxiety and begin to make huge strides once they realise they are no longer in a threatening environment. For most, however, the road to fearlessness is a long one with many points where you feel like you are making slow progress indeed. Staying motivated is vital.