I’ve got a confession to make. I talk about threshold all the time. I can’t think of a training session I’ve done where I’ve not talked about threshold in the last four years. And yet, I know I talk about it as if it’s just self-evident, when I know it’s not.

When we’re working to habituate, socialise, desensitise or countercondition our dogs to various things in the environment, we’re looking for an optimal training level. A teaching zone. There’s zero learning going on if our dogs don’t even notice the things we’re supposed to be exposing them to and yet at the same time, we don’t want to tip them over the edge. Before you start reading, I also need to confess that I’m intending this to be a full primer on threshold, so get yourself comfortable or break this up into small doses. I didn’t want four or five posts all on the same topic, so it’s all in here. I make no apologies, but don’t feel you have to digest in one sitting.

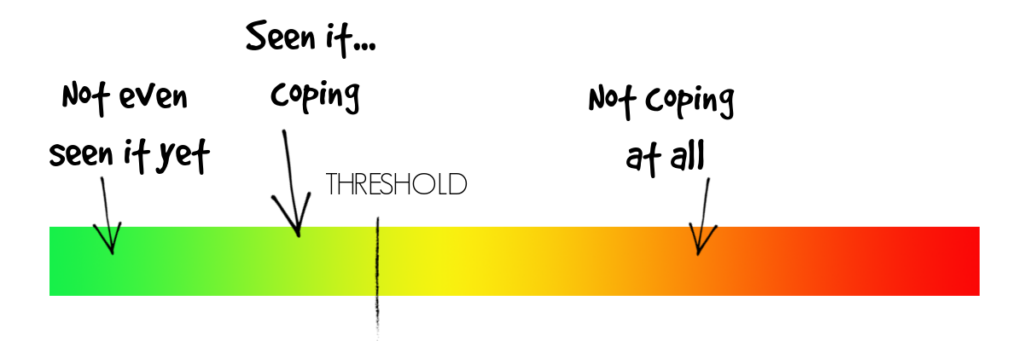

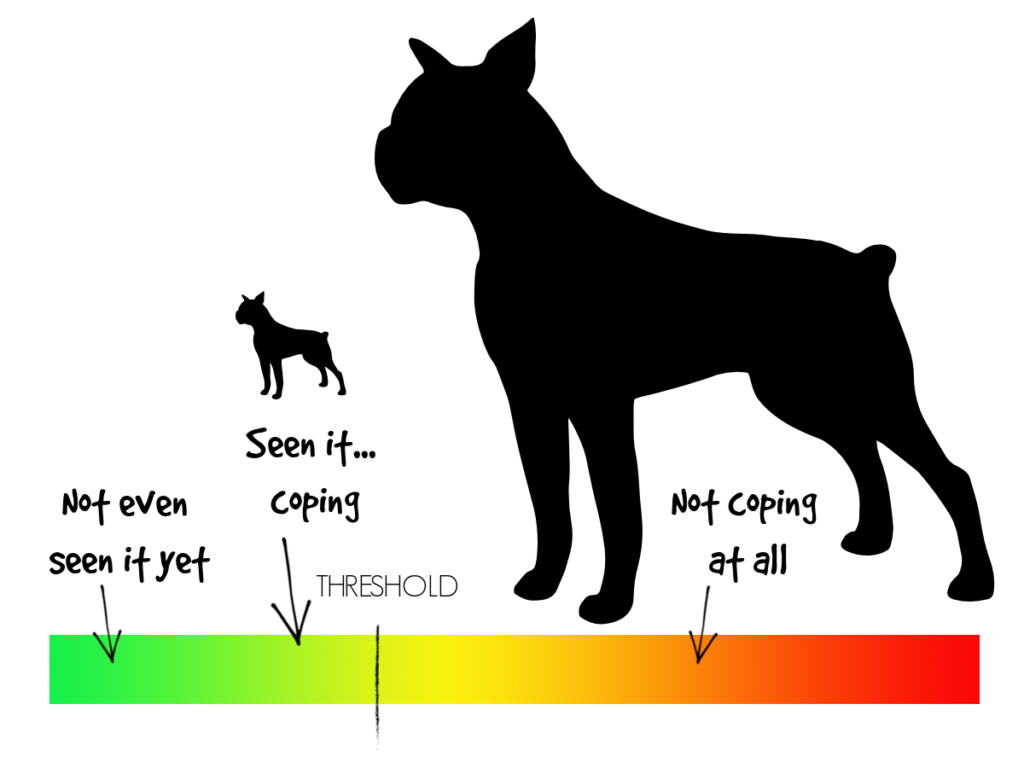

It’s easiest to think of threshold on a spectrum like the one below. Green would be that state where everything is fine and you’re humming along happily through life without any stuff to bother you. You start to move to yellow when you’ve seen something that excites you or frightens you or you’ve noticed it and you’re coping with it. There comes a threshold – and that may be related to closeness or length of time you’re exposed to it – and other stuff as well that I’ll talk about next week – but at some point, we’ll start feeling uncomfortable or stressed, or on the contrary, excited and over-aroused.

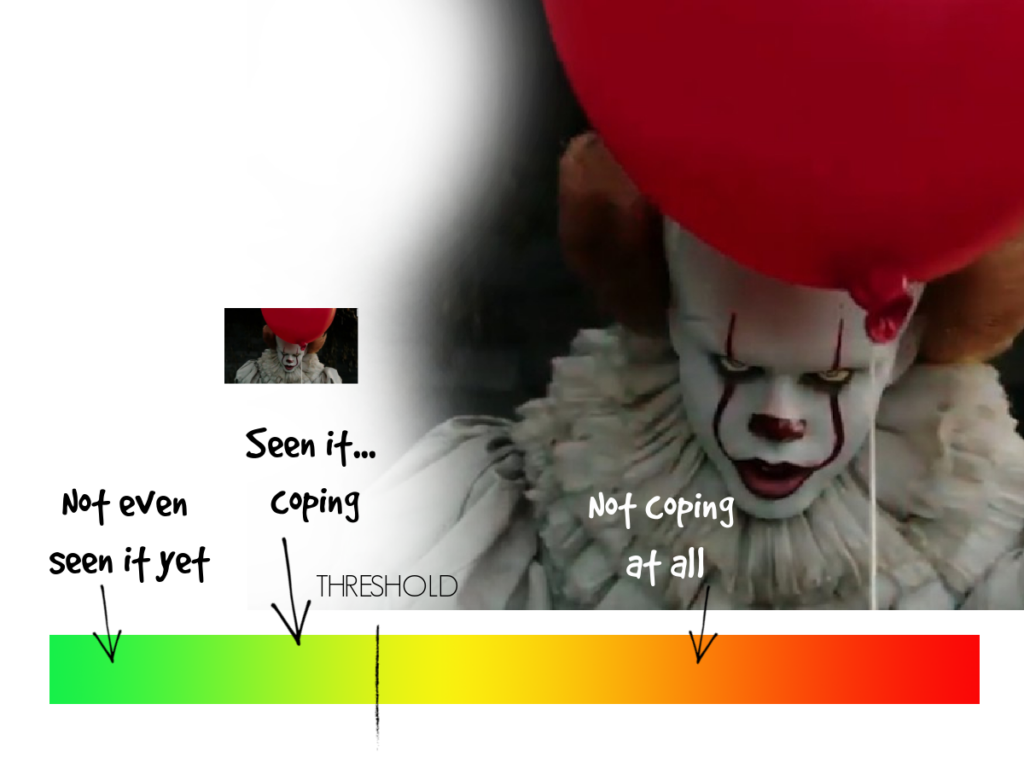

So you might be freaked out by scary clowns… it’s normal. You might just about cope with seeing a tiny picture on a screen on the other side of the room… and then not be able to cope with Pennywise up close and personal. There’s a threshold at which you go from coping to not being able to cope at all.

The same is true for dogs. Imagine your dog has a thing about other dogs…

There are subtleties to the not coping at all – it’s not just all about how near or far a thing is from you, but I’ll explore those in the next post when we’re looking at those exciting things known as stimulus gradients. For now, I’m sticking with simple as this is probably the most common scenario that many of us know.

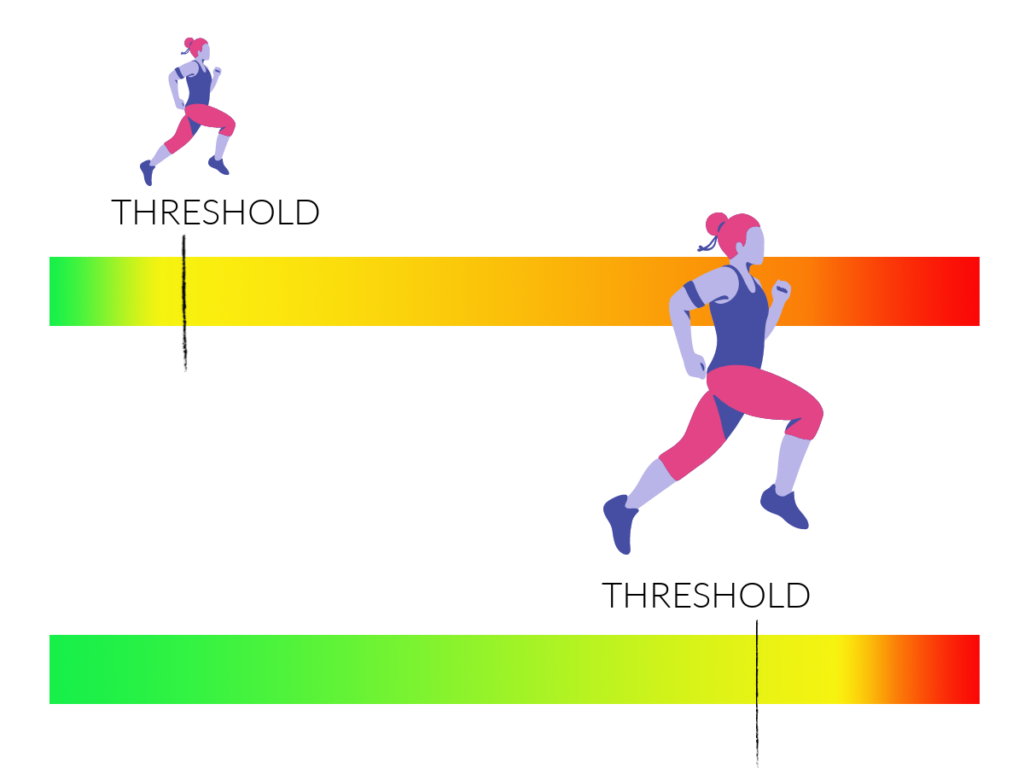

Some of our dogs may have a very low threshold. These are the hair trigger dogs like my own dog Lidy. She’s going into that red zone within microseconds. She’s not only super-sensitive to things but she’s also got a very narrow green-yellow bit.

She sees the scary thing, she is supersensitised to the scary thing and she goes right into biting. Or, at least this was her when I first met her. I’ll tell you about how we can mess with these thresholds later.

Other dogs may be sensitive to certain things. Heston is sensitive to people running towards us. He notices them quickly. But he takes a really long time to escalate through behaviours. So we start with a “I’ve seen them” and it takes a really long time for him to build up into grrrs and then a really long time for him to build up into barking.

Except this morning. He yipped at a person getting out of a car next door. We’d just left for a walk and he was already very excited already. You see, these spectrums are SO not set in stone. Trigger stacking and flashpoints play a crucial role.

But that’s what dog trainers are talking about when they talk about reactivity and thresholds and even red zones.

When you know that spectrum though – even for those exceptional moments like this morning – you can find the teaching zone.

The teaching zone is that period from noticing the stuff and then throwing out ‘loud’ behaviours like growling, barking, airsnapping and biting as well as those other fear responses such as trembling, cowering, trying to escape and so on. You’re always working sub-threshold in that ideal little ground between “Seen It – Coping “and “Woah, not so fast there Buster!”

It’s that sweet spot between noticing things (and remember, that can be scents and sounds too) and being hijacked by emotions or predictable behaviour patterns. You should always be working where a dog can be distracted and is still able to switch their big brain on rather than just getting carried along on a tidal wave of emotion.

It can be really hard to find that sweet spot and stay in it. But when you find it, for reasons I’m about to explore, you will make amazing progress. Where you will make less effective progress, especially if you want the dog to listen to you and follow cues like ‘Watch Me’ or ‘Look At That!’ as we looked at last week in the two taught behaviours every reactive dog owner should know. It’s less bad to be a bit orangey if you’re still using counterconditioning. But you may find that your dog is not even interested in food, for reasons I’m about to explain. If you’re working on desensitisation, though, ALL the exposures should be in that teaching zone. If they’re not, and especially if you have your dog on a lead or in a small enclosed space, then you run the risk of flooding them. The only thing they’re learning there is to suppress their behaviours or practising existing ones until they’re really good at them. There are a lot of dogs who’ve had a lot of practice at barking or growling.

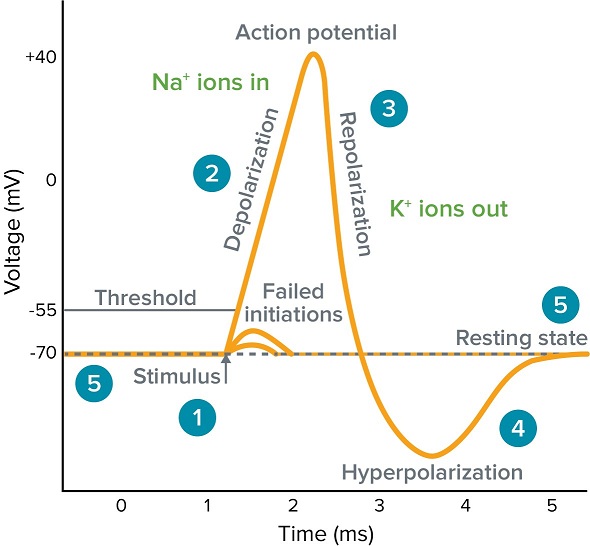

What I wanted to do today is talk about that threshold from the bottom up. Neurons to Biting. Neurobiology to Barking. Anatomy to Escaping. Threshold means different things you see depending on who you are, but they kind of all sit together in the end. If you’re a neurologist studying action potentials, threshold means something different to you. If you’re an endocrinologist studying the threshold for activation of the sympathetic nervous system, then threshold means something different to you too.

For those little grey cells, they need a bit of stimulation to make them fire. The firing is called an action potential, and cells have a threshold at which a stimulus will make them fire.

In order to fire, our neurons in our brain need stimulation. That can be so many things, of course, but could include sensory stimulation for sure.

Lidy’s nose recognises a cat is in the neighbourhood. Her eyes confirm it with a visual. They send electrical and then chemical impulses to various parts of the brain, not least the dopaminergic system of her ventral tegmental area, the reward and learning centre of her brain that says, “Now would be a really good time to chase that cat!”

The first threshold is at a neural level. Every neuron needs a certain level of excitement to get it to send a signal to its friends. Whether that’s an electrical communication like we find in the eye, or a chemical communication like we find with things like serotonin and dopamine, neurons are pretty much sitting around doing their own thing automatically until something excites them. Psychiatrist John Ratey says it’s a bit like the staff in a department store. Just because it’s not open for business doesn’t mean all the staff aren’t working, but as soon as someone walks in, some of the staff will notice you and start to change their behaviour. I like that notion that neurons are just kind of doing stuff right up until that moment when something appears to change their normal routines.

So that’s the first threshold – the level of stimulation needed to make your neurons start firing. If you’ve not seen the excellent Hank Green explaining action potentials for the Crash Course series, you can find it here. Definitely worth a watch if you want to start understanding thresholds at a neural level.

Around 2.10, he says something that is hugely familiar to most dog trainers, and most owners of reactive dogs: “it just needs an event to trigger the action”… same for the whole animal as it is for a neuron. You’ll see also later that he talks about a threshold that action potentials need to be triggered (oh, another word dog trainers know!) and boom, a signal is sent.

As Hank Green explains, a weak stimulus (oh, more words dog trainers know!) might not set off very frequent action potentials, whereas a strong stimulus sets off intense action potentials. As dog trainers and as their guardians, what we’re doing when we’re working below threshold is working with weak stimuli that are not setting off frequent messages to the rest of the brain in a “hello, boys!” kind of a way.

Green also talks about myelin sheaths that coat the axons turning them into supereffective and efficient neural pathways: myelination we know is a process that takes place during early socialisation (only weeks for puppies) meaning that some neurons are hardwired to send action potentials down routes our dogs learned long ago. That means good socialisation and habituation is vital for puppies – a post for another time, for sure.

But neural connections – and a massive oversimplification from someone clearly an interested laywoman not a neuroscientist – work on a “Use it Or Lose it” kind of process. If you don’t use it early in life, then the brain just trims the connections and neurons die a lonely, unused death. And if you don’t keep using it, the same. However, the more you use it, especially in those critical periods as our puppies grow up, those neural pathways become superhighways insulated with myelin making those signals superefficient. The brain even pushes certain actions down into automatic behaviour. Like you don’t still have to think about Mirror-Signal-Manoeuvre every time you drive the car, and all that effort you put in to learn to ride your bike gets pushed into automaticity. You just do it. That said, if you leave it 20 years between your first tentative experiences of driving, you’re probably not going to want to get in on the Le Mans 24 hour race or try to navigate Milan in rush hour. Automaticity can get rusty. If our dogs learn early enough that barking puts people off coming any closer, and it’s myelinated not long after, as well as repeated, what you’ve got there is a bunch of neurons that are not only sensitised to that particular stimulus or trigger, but also really, really efficient at doing it. But if their early learning was only superficial and they never really learned to cope, then it may not be as automatic or well learnt as you assume.

Puppyhood and early learning count very much indeed, and habits are really tough to break, especially if you learned them at an early age and you’ve had history of practising them. This is why knitting came back easily to me after a twenty year hiatus, but learning to crochet was like learning Ancient Greek because I’d never done it before. Sure, I didn’t start off knitting complex things, but gradually easing myself into it got me on to multiple thread, double pointed needles kind of stuff in no time at all. Whereas I’d never learned crochet at all. No wonder it was hard. Or, at least, that’s what I tell myself.

It all means that our neural pathways can become more efficient or less efficient, can give way to automatic reactions rather than thoughtful conscious actions, and can also become sensitised.

Our thresholds for brain activity change, become more sensitive or even die off. The action potential threshold might not change, but when you’ve got a bunch of neurons firing really quickly, other bits of the brain listen – especially, and this is so important, when it’s the amygdala that’s shouting it. You know, those almond-shaped bits that are in charge of fear learning. The amygdala shouts really loudly to the hippocampus, in charge of the nervous system. When you’ve got a sensitised amygdala, your threshold for reaction is much lower.

We see this all the time with our dogs, how they become more sensitive to certain events. Especially if these events happen in puppyhood, our dogs learn quickly and easily and that myelin sheath lays down insulation so that it’s even easier for the brain to send messages from one part to another.

Triggering the threshold of a dog (and a human) works, then, at a neural level.

It also works at a behavioural level. At first, signals are weaker. Like me, when my brother harasses me. Stop it. Stop it. Stop it! Stop it!! Pack it in!! STOP it!!!! STOPPPPP ITTTT!!! And then the knives come out….

There will be a threshold at which whatever irritating, annoying thing he is doing will trigger me to say “Stop it!” and the more he does it, the more sensitive I’ll get. Plus, I’ll learn that “Stop it!” doesn’t work and I need to stab him with a fork much earlier, since that’s effective.

For our reactive dogs, that’s the same. And just as some people are very tolerant of aggravation, and some are set on a hair trigger, the same is true with dogs. That threshold – the stimulation you need to set you off – will be higher or lower depending on loads of factors. And each trigger – or type of trigger – is different. I’m super tolerant of children and animals. Very, very intolerant of grown ups. I’m also bound by social conventions, just as dogs can be, and I’ll give warnings before I explode.

That’s essentially what threshold is, from the neurons upwards: the level of excitatory stimulation I need before I react. Complicated as it is, that’s why my dog Flika needs a certain volume of low-flying aircraft before she needs to bark at it, why Heston needs a certain proximity of people to the property before he needs to bark at it, and why Lidy has five hundred triggers for her super-sensitive neural networks.

Impulses – like my desire to stab my brother with a fork – can be mitigated and suppressed by punishers, like my parents hanging around. Also by social convention that says you shouldn’t stab your brother with a fork. Also by cognitive processing and rationalising that says although it would be fun to stab him with a fork for teasing me, that in actual fact, it would be a very inefficient way of getting him to stop and I’m likely to look like a crazy woman. Those things alter our thresholds too.

Dogs have things that mitigate their impulses too. Just like us, good socialisation can help us learn how to deal with grievance without stabbing people with forks. Rules and restrictions can be inculcated just as they are when we teach dogs not to bite us or that it’s not acceptable to draw blood and so on. Lack of practice can help neurons die off. Habituation and habit building create other patterns of behaviour that we learn are very effective, like telling Mum that the brother could do with some Time Out, thank you very much.

Pain also affects thresholds for reaction – you know yourself if you’re having a bad day, you’re more likely to be reactive to stuff that doesn’t normally trigger you.

Collective triggers can also push you over the edge. You know this too if you’ve been working all week and you’ve had to cope with innumerable stressors. Trigger-stacking 101.

Hunger, lack of sleep and other basic physiological needs can also make that threshold more sensitive to triggers. Basically, the whole system is set up to make us more sensitive, not less.

But essentially, those triggered action potentials are not very much of a problem for us unless they trip the autonomic nervous system.

I’m sure you remember the autonomic nervous system from high school biology. Those automatic actions our bodies just get on with, kind of like the software humming beneath the surface of your laptop or phone that just happen in the background. Virus checking and temperature monitoring and input analysis. And if something should trip that parasympathetic nervous system from rest-and-digest, feed-and-breed, then we’re into life-or-death sympathetic nervous system stuff. You know, pulses racing, digestion stops, lung capacity changes, large muscles gear up for flight or fight. This fight-or-flight response is well known (and don’t forget flirting and fidgeting for dogs too, especially if you have social dogs who may be using these behaviours to signal their discomfort). That trigger – the switch from parasympathetic to sympathetic – is what OUR threshold in dog training is all about. Not triggering emotional responses that demonstrate the dog’s sympathetic nervous system is at work.

Hank Green gives another really useful explanation of the autonomic nervous system here:

And the bit you’re really interested in NOT triggering… the sympathetic nervous system.

It’s just useful to bear in mind that when that threat system is triggered, digestion is not the primary focus. That’s a sensible reason to keep under threshold when we’re training with food. Don’t forget too that things like twisted stomachs can be linked to stress and the engaged sympathetic system – that food isn’t being digested; it’s just sitting there if your dog is even eating at all. I know a couple of dogs who’ve had stomach torsions as a result of eating big meals too close to their sympathetic nervous system having been triggered by things like grooming or vet trips. You should be alright with small pieces of highly digestible food, but even so, it’s a stark reminder of why we need to stay under threshold. As Green says, the frequent triggering of the stress response can have nasty consequences. That’s not just for people, but for dogs too. If your aim is that they get used to or habituate to stressors and triggers and stimuli – whatever name you’re sticking on them – then keeping putting them into stressful situations can cause all sorts of health complications. Cushings dogs are another type of dog who definitely don’t need the cortisol of a stress response, thank you very much. But you don’t have to be a deep-chested dog or a dog with Cushings to suffer the consequences of triggering repeated stress responses. Another reason why we need to stay in the safe zone under threshold.

If your food isn’t working and your dog is normally pretty food motivated, then you may want to work out if you’re too far over threshold or not. Clue: you probably are, and it’s not just going to hurt your ability to train your dog, who is in fight-or-flight mode, or ready to chase some small critter, but you also may run the risk of long-term health fallout. A small amount of positive stimulation is good; a prolonged or acute amount of negative stressors is incredibly bad.

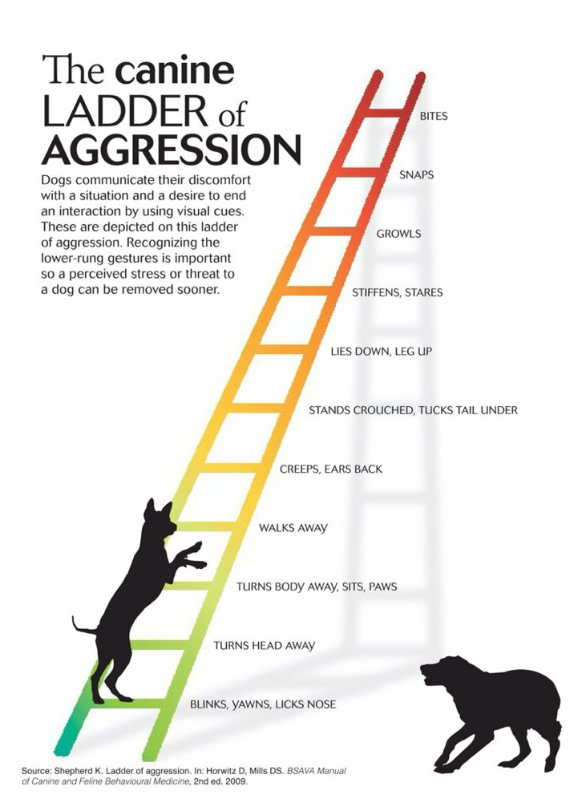

For most of our dogs, we just don’t realise that they’re close to threshold. We miss the quiet signalling and the occasional behaviours. We miss the lip licks and the shoulder turns and the yawns and the eye contact. We only listen to the shouty, arsey behaviou

Here’s a video of the Baby-faced Killer, Miss Lidy La Moo, playing with Heston. Or attempting to. Let’s look at those various behaviours and discuss thresholds a little.

I usually don’t let her attempts to engage him go on this long. He doesn’t like it. I shall tell you why. Not loads of signalling, but he doesn’t reciprocate. He’s just tolerating her. There’s a couple of moments of whites of eyes and a little lip licking, a few looks to me to reassure him that I’ll step in. He stands and there are very few bodily parts involved.

The more she pushes, the more muscles and limbs are involved. At first, it’s just his ears flat back, a bit of turning away, a bit of a lip lick, a shift in body weight. Single body parts, small movements, quiet communication. Then he steps in as she moved away. More body parts, bigger movements, louder communication. Another lip lick. Some concerned whites of eyes. Not sure if her scratch is displacement or a real scratch as she had a bit of an itch at the same spot earlier off video.

Around 20 seconds, he neatly steps away. There’s some amazing and incredibly subtle communication after that. She stands, he looks at her, her tail position drops from big old rudder tail to slower, lower less offensive wagging, That little twitch of her ears before she pounces on him… so subtle. Single body parts and quiet communication. She then forces him into moving because her behaviour gets bigger, forcing him off his spot, involving all those body parts. Bigger behaviours. She triggers his threshold for movement with that little head going to his manly undercarriage (oh, that’s what makes the big black dog move, Lidy may realise!) and a behaviour has been made to happen – not unlike my little brother keeping up with low level tormenting until he gets what he really wants – the Emma Explosion. Small to big, single body parts to whole body, quiet to noisy.

This, of course, is just something fairly innocuous. I don’t let her keep pushing him because it never ends well. But recognising all those little signs are absolutely vital. Know what your dog looks like at the bottom end of the spectrum. We focus too much on the top. I can’t begin to tell you how many clients have wanted me to “see” their dog reacting. I promise you I know what barky, growly or bitey dogs look like, as well as dogs who are afraid. What I want to see is what do they look like when they’re not reacting and what behaviour marks that change that the neurons are starting to get excited and what marks the moments before your dog will have an emotional reactions. Really, in my opinion, we focus far too much on what our dogs look like when reacting and we’re not thinking about those moments when they’re figuring out whether they need to or not.

Knowing the way your dog looks when they’re in that ‘teaching zone’ – ie they know the scary/fun stuff is there but the big brain is still switched on and they’ve not tripped the fight-flight-flirt-fidget sympathetic nervous system – is essential. This photo is exactly that.

This is Heston’s teaching zone behaviour: still, head and eyes looking at the thing (in this case a departing dog and his minders). Ears alert, head following, mouth open, is vital. In that teaching zone, you’ve got a tiny teachable moment when your dog is still deciding what to do about stuff.

Here, you can see Lidy move from green zone – just scoping – to yellow. Ha-ha. Noticed you! Mouth closed. Head pointing in the direction of the stimulus. Even for my dog with the tiny, tiny teaching zone, there still IS a teaching zone. And by keeping within it, over time it has – miracle of miracles! – got bigger. She moved from yellow to biting as quickly as you or I might move if faced by Pennywise. Seen You – Bite You. Now there is a teensy tiny reflective moment between Seen You and the next bit. A tiny moment where decisions are made. Growls sometimes come out. You don’t know how glad I was to hear those teensy growls! Sometimes she does barks now. Lidy is literally learning the stuff in between green and red behaviours.

Dr Kendal Shepherd’s very useful ladder of aggression is a good tool to see those behaviours in a gradient:

It can be tough for us to recognise those low level behaviours and I’m yet to be convinced that they happen in a continuum, but I think they’re absolutely bang on in terms of the seriousness of the level of stress they communicate, even if I think they don’t follow on from one another. You can see in the video those tiny microcommunications Heston gives, the lip lick, the turning away. There are loads and loads of other useful signals you can find on Silent Conversations

So with Lidy, I’m just filling in the blanks and stretching out the yellow bits, shrinking the red. It’s not easy and it’s not fast, but I didn’t adopt her thinking it would be.

Case in hand: I had to go away briefly recently and I needed to depend on a very lovely friend to look after Lidy. They’d met once for a test on site and things went swimmingly. The day I was dropping Lidy off, I took off her lead – and she went bombing over to my friend as if to do a full-on Malinois take-down. My amazing friend crouched, made nonthreatening and did a mammoth “well, Lidy! How are you?!” and defused that bomb in the time it takes a Malinois to go 10m at full pelt. You know when you see superheroes change in mid-air? My little Jekyll and Hyde girl went from Hyde to Jekyll within that 10m run. The fact that she can even change from one tactic to another at hyperspeed is testament to how far she’s come. At the same time, it’s also an example of how hair-trigger some dogs can be. But also how you can work on that. What you end up with – eventually – is a much bigger teaching zone and being able to move those red zones back to much less sensitive yellow and green zones. Said friend reminded me about PTSD last night too, and it really does make me wonder if I need to reframe Lidy’s behaviour a little. I’m glad to be able to offer you her story though as I know it’s very easy for trainers to talk the talk with their purpose-bred, carefully reared showdogs and agility dogs. I’m walking the walk, I promise. Her journey has been an education for both of us. But it makes a difference when people can send you photos of your chilled out dog having an absolute blast with someone who is not you. Learning to love humans is not easy, but she does have a good number of friends among the staff and volunteers of the refuge where she lived for 3 years.

Her world will always be a small one. She is never going to be able to cope with all of life’s triggers. Her green zone will always be small. That’s fine. Unless you are a fine and robust person yourself, you probably can’t either. Spiders, scary clowns, flying, public speaking… there’s probably something in there that does it for you. I’m a pretty robust person myself but I can’t stop myself being creeped out by ants crawling on me, by spider webs and by bats. And I love all creatures. Expecting Lidy to cope like an assistance dog bred specifically not to have that very tiny green bit of the spectrum is too much of an ask.

Despite that, a number of clients start off with the notion that they can turn their nervous Nelly or their bitey Betty into a dog who will cope with all triggers and whose threshold will never be tripped. A dog with a huge green zone. One of the most important things I can say about that is to reassess what your dog is capable of.

The other is to remember that these behaviours serve a purpose for our dogs. Sure, I don’t want Heston to bark at joggers. We’ve moved that threshold very nicely and made that teaching zone so very, very large to the point that it’s almost a non-issue.

At the same time, it’s perfectly acceptable, in my opinion, if the jogger turns out to be a purse-snatcher and for Heston to bark and make them think twice about stealing his handbag. Or mine. Heston seems to be of the opinion most joggers might do this if you don’t keep an eye on them. But I’m happy it’s just a watchful interest rather than dressing down people breaking into a sweat some 200m away. Do I need him to be able to cope with the London Marathon? Nope. Not in this lifetime.

So let’s be kind to our dogs when we think about their triggers and their thresholds. Let’s be realistic.

Let’s also remember that engaging in desensitisation and counterconditioning should be below threshold but that you’re still asking your dog to do stuff that ultimately wouldn’t be their choice.

YOU may know that the long term goal is a net gain where feeling good is concerned, but what mostly feels good to scared dogs is stuff being far away, and what feels good to dogs who like chasing is doing exactly that.

We’re asking them to change their behaviour without them understanding that they may be able to lead a more full life that may be infinitely pleasurable. You know that. They don’t. They didn’t sign up for this, to have to you take the fun out of chasing sheep or to have to take the safety out of scary stuff being kept far away. So we need to remember to do it in the most innocuous ways we can – for their sake.

And let’s remember that we may have to compromise. I won’t take Heston to the London Marathon and he promises not to bark at the occasional jogger. I won’t expect Lidy to be a social butterfly when “Us” being Good and “Them” being Bad is part of her very dodgy DNA that her former owner did absolutely nothing to address that in her early life. And I promise that she doesn’t have to learn to cope with people who don’t really understand dogs – even if they like them. I promise nobody will hurt her. And that means accepting she needs a much smaller, safer life than I would really want for a dog. In turn, she’s learning to put trust in me that the world I offer her is a safe one. It means I need to accept that green comfort zone may always be relatively small compared to the average spaniel’s and will be minuscule compared to a super socialised labrador. And that is perfectly acceptable.

If you’re VERY interested in neurons, sympathetic nervous systems, triggers and learning, the eminent Robert Sapolsky is well worth 90 minutes of your time. I think I’m responsible for at least 100 of the watch count on this video.

Next week: stimulus gradients – what they are and how they can help you train your dog.