What do dogs have in common with trolls? Sometimes, they take offence at goats trip-trapping over their bridge. Okay. Not sometimes. Quite often. And by goats I mean humans and other animals, and by bridge, I mean by their window, by their door, by their gate, by their kennel and by their crate. This week, dealing with a couple of territorial dogs and a crate guarder, it necessitated a bit of a detour from the article I was planning on writing about overcoming arousal around a trigger. That said, this article in itself is about overcoming negative arousal around a trigger, so you can see patterns in play here that you’ll see elsewhere too.

So why do dogs guard spaces?

Dogs are predators – even the littl’uns – and predators, by their very nature, often have a ‘home ground’ or range. Even free-roaming dogs, street dogs and community dogs will have a patch that is largely defined by how many other dogs there are in other patches, and what resources there are. And just like the gangs in The Wire, they expand to fill the gap and to take advantage of available resources. Dogs are generally affiliative in these circumstances and seek to avoid confrontation, often in overlapping territories. But they’ll engage in ritualised aggression to see off intruders and defend their area if under threat: they don’t give up without a fight. Funny that. Sounds like a lot of people too.

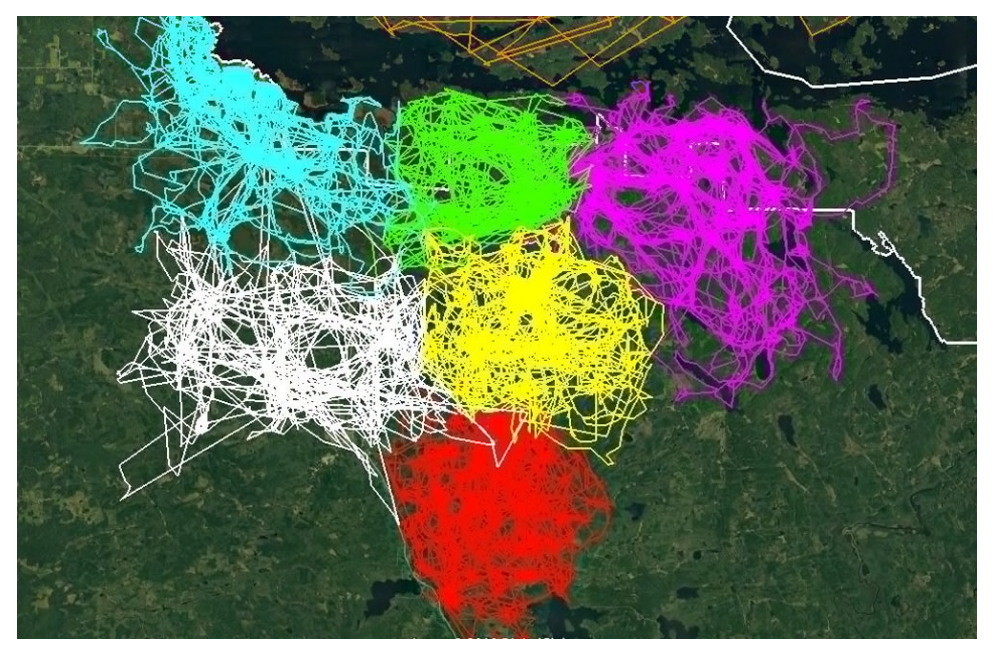

Here you can see the very well-defined territories of six families of wolves in Voyageurs National Park in Minnesota

You can see how little overlap there is… the saucy white group occasionally foray into enighbouring territory, but look how neat that yellow group is. Some squabbles around the edges, but a very clear ‘this is our bit, that is yours’.

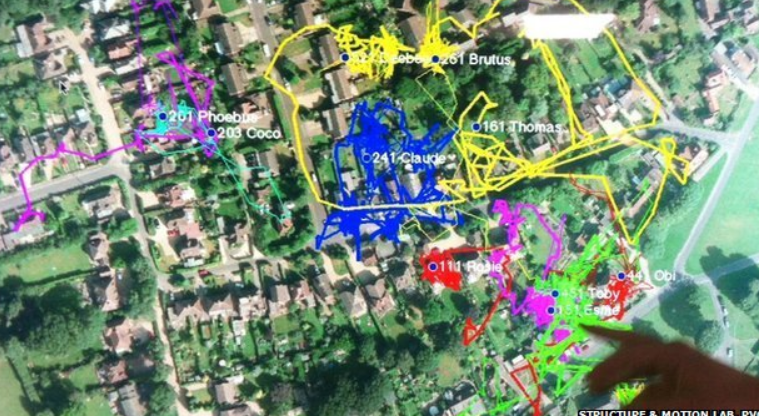

Domestic free-ranging cats have a similar map:

Now clearly dogs are not wolves or cats, but what evidence we have from street dogs and village dogs shows a very similar pattern. Sometimes dogs who are free to go their own way are drawn into other areas at times when food becomes available, or there will be lots of overlap. What we know about street dogs is that, like cats, they are drawn away from their own territory by resources and they also follow human geographical features. Though you can’t see it in the top image of the wolf movement, there is an orange family at the top. I can”t remember if it’s a river or a highway that divides the cyan, green and magenta from the orange group, but there’s either a geographical barrier or a man-made barrier there.

Territorial behaviour is fairly pointless for many domestic pet dogs, but humans have specifically selected in many breeds their ability to stay in a territory and guard a resource in that territory. Dogs aren’t just used for finding drugs stashes, but are used more and more to guard them, as well as guarding houses, yards and herds of animals. So guarding a space and protecting it from intruders are behaviours that comes naturally to a dog.

It’s a throwback behaviour that is often no longer useful in the home but we often profit from. Dogs do make us feel safer, even if it’s a tiny little pomeranian alert barking at the postman. That’s one reason dogs can be territorial over space: it’s been a useful behaviour through history. Plus, though they are not cats, they do love a nap. And nothing is worse when you’re having your nap than someone coming up to you and interrupting your napping by coveting your bedspace. Thou shalt not covet your neighbour’s bedspace.

Encroachment during resting is one worth a show of aggression or actual aggression. I have at least a client a month whose dog has bitten someone who came into their eating space or their sleeping space. And I have at least another client a month whose dog has bitten someone who came into the yard or garden.

Pet dogs have another factor to consider, however, when compared to wolves, cats and street dogs. They are more bound by fences, walls, gates, windows, even leashes and cars at times – things that don’t bind a free-ranging dog.

Normally, free-ranging dogs don’t also have to deal with the psychology of the barrier.

Fences, leads, gates, windows, doors… they’re all laden with frustration and fear for dogs whose movement is controlled and restricted.

You’ll certainly find videos of dogs on Youtube going mental at other dogs behind a fence and then wagging their tail when they get to the open gateway. I’ve even written about it here.

My dog Heston does this with our shelter guard dog Belle when I get to the shelter: he barks, she barks, the gates open and they’re ‘Oh hi! It’s you!’.

These behaviours are one reason why dogs might be territorial and protect their home turf from unfamiliar dogs or strangers. That includes any ‘non-family’ members such as neighbouring cats, next door’s dogs and even your neighbours. Just because the dog should know who the other animal or human is does not mean that that knowledge will overrule territorial behaviours.

Fences are a little different than lead aggression. That boundary line is not just drawn in the sand, a notional, temporary boundary. It’s a physical, actual line. It defines ‘intruders’ and ‘family’ very clearly. Inside, you belong. Outside, you’re an intruder. For dogs who guard, fences, walls and even windows are very clear, well-defined markers of where ‘friends’ are and where ‘foes’ are. Their ‘Halt. Who Goes There?’ is just a bit noisier and canine than ours is.

Some dogs are spectacular at controlling entrance points and exits.

Do you think Flika was lying here just because there was a cool surface and a cool breeze?

It’s a possibility for sure.

Clearly she had fallen asleep on duty here, but right next to the gate?

Flika had been a guard dog most of her life, and doors and gates were her thing. Control the doorway, control the things coming in and out.

So even when it’s not particularly a problem, our dogs might not cope well with canine or human intruders very well even if they manage it without growling, barking, lunging, snapping or biting.

I think we all accept that a dog on the property might not be welcoming if we don’t know who they are.

Many dogs start to feel on edge long before they see a person approaching their crate, bed, house, garden or kennel. Heston will bark at things in the garden that are a good 50 metres away if he can see or hear them approaching. Many dogs can see moving things over 400m away. Their hearing and sense of smell is far more acute than their vision, as well.

Part of that is sometimes the sound of approach without being able to see the ‘threat’: dogs often hear a threat before they can see it, like the sound of a post van approaching. This is then intensified by seeing the ‘intruder’ approaching. It can also be worse with ‘sneak’ approaches which must seem like nothing short of an ambush to a dog from some stealthy ninja, rather than just the approach of a cat.

Part of approach reactivity is also the tension of the body posture of the person who then continues to approach: we are on edge of course when we approach a dog behind a barrier, be it a window, a grille or even a door. We speed up to get it over with. We take a direct route and we may keep our eyes on the ‘target’ entry point in case the dog comes bursting through it. These behaviours are very confrontational for a dog and if they can see us, they no doubt confirm the bad intentions they think we have.

Part of it is also learned behaviour. Many ‘watchdogs’ are on guard most of the day, and in their heads they are very effective. They spend the whole day practising when we are not there. Every time a car pulls up, they bark and in their rationale, they are responsible for preventing an intruder when it drives off. Every time a passer-by goes past the window, they approach… the dog aggresses… the people walk off. To a dog, these events are connected, despite the fact that there is no connection between their barking, snarling and aggressive posturing. That behaviour is practised over and over and over again.

Whilst it may seem irrational to guard a derelict yard, a concrete kennel run or an empty metal crate, to a dog, this is its space. I often think they see it almost as armour. Space is a valuable commodity to a dog, and a fence, wall or barrier means the boundaries are very clearly defined. They also seem to have no concept that an intruder cannot get in and they are safe in an enclosed space: otherwise, why bark at people or cats at the window?

So when they feel under attack from an intruder, be it a jogger, car, cat or burglar, even someone coming to walk them at the shelter, dogs growl, snap, snarl, fling themselves at windows, hammer on fences, throw themselves against doors… or they go low, protecting what’s inside, preparing for attack. For fearful dogs, they will seek to escape to evade. And if they can’t escape, they will hide, seeking out kennels to hide in or couches to hide beneath. You’ll find them at the back of their space, as far away from entry points, small as they can be, trying to show that they are no threat.

If a dog is protecting their space from their own guardians or other family animals, then that can cause some difficulty. We all understand that a dog might bark in the yard at unfamiliar people passing. There are at least ninety Shih Tzus who like to tell the whole town that people are going past and they ought not to bother with trying to stop by and drop in. That’s fine. Somewhere it makes sense to us that these dogs are just doing their job.

Yet when our dogs guard territory from us, be that their bed or a couch, a crate or even a doorway, it can feel like a massive abuse of trust.

After all, they’re now a troll lurking in our own home, often making us afraid to move around.

There aren’t easy solutions, either.

So what can you do?

#1 Get your puppy’s socialisation and habituation right

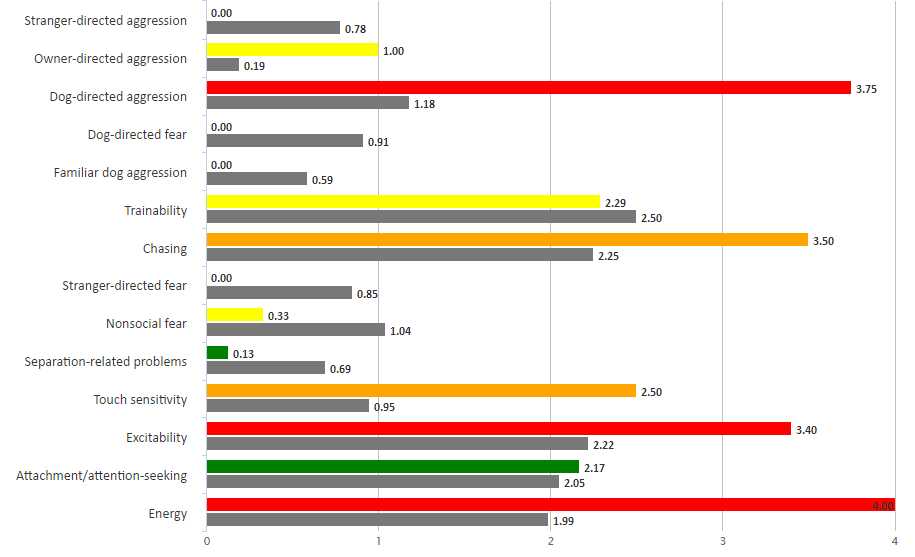

Socialisation and breed play a part in how well dogs handle intrusions onto their territory. If you are getting a breed renowned for ‘aloof’ behaviour or who have been used for guarding anything – be it sheep or human property, then know that you need to be sensitive about their early education relating to space and territory.

There are lots of reasons why a dog might behave aggressively or fearfully on approach. Those reasons are sometimes hard-wired. It’s one reason proposed as to why we kept dogs around us all those thousands of years ago. A sentinel dog with their enhanced hearing and nose was a useful way to protect ourselves from other predators. But dogs are responsive to the environment. They guard because they learn it keeps strangers out.

In those early weeks, we can also help to make sure our puppies feel comfortable about us moving near to their resting spots. If you’ve got a dog who was badly habituated to human movement from 3-8 weeks, then you’re going to have your work cut out. For puppies left largely to their own devices for 8 weeks where humans only pop in from time to time, the fact that fear starts to set in around this point is important: they run the risk of leaving their mother having never learned that humans move about in their space. Puppy farm dogs or those raised in barns or outhouses, or even those raised in completely separate, isolated rooms, are at risk of missing out a very important bit of socialisation. No wonder they’ll then grow up to feel uncomfortable about human beings wandering around in their space.

One of the saddest cases I ever worked with was a labrador who’d been raised in a very nice, clean purpose-built kennel. He never slept in a place where humans lived. He played in their home, he played in their garden, they all spent time together. Going to his new family at 11 weeks, right in his most sensitive moments where fear learning can be very damaging, he never quite got used to humans moving about when he slept, and age 11 months, he’d had enough and bit a household member.

Putting dogs in crates may keep us all safe, but it can actually intensify problems in many ways as it traps the animal in position where they can’t seek out space.

When things get noisy around here, Heston takes himself off to the bedroom and tucks himself in between the bed and the wall. That freedom means he can easily choose where he wants to be.

Yet when a neighbour unfortunately came into the house without announcing herself when Heston was 14 weeks old, Heston totally lost it. He barked for about 10 minutes and he never, ever felt easy about intruders coming into his space again.

We need to be careful with socialisation especially when we have a breed sensitive to territorial behaviour. Heston is a tiny part GSD and a whole lot of Belgian shepherd, and had I known what I know now, he’d never have had that scary experience and I would have inoculated him more effectively against this by building up in small doses and pairing intruders with wonderful, wonderful things.

#2 Medical interventions

Another thing we might consider might well be sterilisation. Many vets recommend sterilisation for any form of aggressivity despite evidence being contradictory.

Studies show that territorial issues in male dogs can perhaps be mitigated in some circumstances by sterilisation, but they can be worsened too. It’s very complicated. Sterilisation also has other fallout that you need to be mindful of. For dogs who are fearful of social interactions, testosterone may well be playing a factor and it’s easy-ish to try a synthetic testosterone suppressant such as Supralorin to see if that makes any difference. Be warned: supralorin can cause increases in aggressivity at the beginning, so it’s not an immediate cure-all. However, unlike castration, it’s not something you can’t undo. More and more vets are prepared to leave the gonads intact and perform a vasectomy, which can help leaving testosterone in place but mean that there won’t be any accidents if you were thinking of sterilisation as a way to manage breeding.

You may also want to think about your dog’s level of anxiety in general. In my experience, when dogs are guarding spaces from their guardians, it’s not necessarily about anxiety but about trust, but there are certainly dogs who you may want to check with your vet about whether behavioural medication may help a behaviour modification programme work more quickly.

Also, if you are struggling with your dog guarding their bed, kennel or couch from you, then you need to think about whether it’s at certain times of the day. Many of my clients who have had this problem say their dog is more aggressive towards them at night. This obviously leads us to think that it is about vision, especially since we are very visual creatures. However, more often in my experience, it’s about the fact the dog hasn’t rested properly in the middle of the day. It happens often in teenage dogs who are coming to social maturity and it can be related to overall lifestyle factors like arousal and impulsivity. It’s well worth a vet check for the dog’s senses. Older dogs may of course be suffering from arthritis and the idea of being manipulated when they’re resting can be horrible. For older dogs or dogs who have just started with these problems, it’s vital to have a check for musculoskeletal problems. This weekend, a new client contacted me who’d been bitten when she approached her dog in his bed. He was 10 years old. She first told me the dog didn’t seem to be in any pain, but then she told me he struggles on certain surfaces. That to me is a clear sign of mobility issues and we can see why a dog might feel more defensive when they’re resting.

Although you might not think to check with your vet or consider your dog’s sleep-wake cycle or general arousal levels, it’s definitely worth a quick stop at your vets.

#3 Understand your dog’s body language better

Many of us simply fail to notice that our dog feels uncomfortable with our approach.

Some dogs might exhibit fearfulness, like the girl below:

Small signals such as looking away, turning a shoulder away, averting eye contact, long blinks, lip licks and even putting ears back can precede confrontational behaviours such as growls.

Tilly, my notoriously guardy little spaniel, was also a notoriously wonderful communicator: looking away and averting eye contact, licking her lips and ‘going low’ all preceded growls and snaps.

Understanding our dog’s body language can really help.

#4 Manage the situation better

Always make sure your dog has a safe yard if they are aggressive towards people or dogs outside the property. Work on the principle that you need two points of security. One single lock is not enough. I’ve currently got a bolt and a chain on the gate. I do not want anyone getting in by error.

If your dog is guarding space in the home from familiar family dogs or from the humans in the household, make sure all your animals have safe places to sleep and rest.

I don’t have a problem at all with dogs being on couches, but if your dog has a problem with occasionally having to tolerate you there, you’ve got two options: either get another couch that’s just yours, and block the dog from getting on it whilst encouraging them to stay on their own, or get a very lush dog bed, block the dog from getting on the couch and encourage them to stay in their own beds. Blocking needs to be permanent: you can’t have the dog on the couch when you’re out. I’d suggest a puppy-pen framework up temporarily but bear in mind that this might worsen the problem for reasons outlined above.

If your dog is having trouble with other dogs getting in their case, you’ll need management but also to see a qualified behaviour consultant with a lot of experience in in-home aggression. Life changes, and a dog who has become blind and deaf may not realise he’s about to intrude upon another dog sleeping. Outside of management situations such as that, having someone help you know what to focus on can really help. Clearly the ideal is that dogs are polite to one another and don’t mind getting in each other’s sleeping spaces or sleeping next to other dogs who might move, but not all dogs can cope with that. Set beds and clear boundaries, particularly around young and exuberant bouncy dogs, can really help others cope much better.

Sleeping alongside each other is a big thing to ask of dogs who don’t like each other. The same is true when it comes to expecting dogs who don’t have a good relationship to cope with bed-hopping.

This photo of my two boys Amigo and Heston was taken about six months into a relationship that had started in the worst way. This was very much their choice and clearly, troubles had ceased by then.

There were months, though, where Amigo needed his own bed that was just his. When he decided to start resting elsewhere, that was on him. It was truly his decision.

When did he make it? When he felt safe.

Management helps with that safety.

Later, when Amigo had a couple of strokes, got vestibular disease and ended up with canine cognitive decline, he went deaf and couldn’t hear Heston growling if he was about to get in bed with him. A child light really helped with that so I didn’t have to leave the lights on all night long.

Management is definitely your friend.

#5 train nicer behaviours

Since territorial and resource-guarding behaviours are very much underpinned by emotional undercurrents, you will need to work on changing your dog’s emotional response to approaches.

The first thing to do is to accept that there are times when dogs can be outright offensive. Tilly’s dying act was to tell Flika off for approaching her as we sat on the couch together sharing our last cuddles. That is a perfectly acceptable impingement of territory. It’s not that Flika was rude. She just saw that petting was on offer and came in to make the most of it. Tilly growled and lunged to snap at her. Flika got the message. Sometimes we can be so overprotective of our dogs that we forget that some assertive behaviour is absolutely fair game if someone has transgressed the rules.

The second thing to do is work with a behaviour consultant to design a programme based around three things:

- Systematic desensitisation

- Counterconditioning

- Operant training.

The approach outlined is aimed at changing a dog’s emotional response to a regular ‘intruder’, be it a staff member in a kennels, a volunteer dog walker or a person who finds a canine ogre guarding their bed, couch or crate. It works for fearful dogs as well as it does for dogs reacting in other ways.

UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES SHOULD FEAR, PUNISHMENT OR CHASTISEMENT BE USED.

These will undoubtedly turn a negative experience into something worse. A dog who is reactive to people approaching is not going to be made to feel better by yelling, shouting, reprimands, shock collars or spraying it in the face. Nor is it going to be made to feel better by confining it, removing it or punishing it physically. If you are afraid of burglars, someone coming into your house and yelling at you will not make you feel more calm or relaxed.

It makes me hugely sad to realise on Youtube that many people find this approach reactivity to be a battle for ‘dominance’ and seek to frighten an already frightened dog into submission. Even my neighbour trainer who uses a range of physical punishments actually realised a dog protecting their space was actually frightened, and calmed him down rather than punishing him.

When I see still, frozen dogs, it makes me so sad. It is most sad that so many ‘dominance’ trainers fail to see how fearful the dog is. I don’t see a dog who has ‘learned’ to overcome their fear of things approaching a kennel or crate, I see shut down dogs who are terrified to move. I wish I had a penny for every time a so-called balanced trainer or ‘dominance’ trainer said the dog was ‘totally calm’ or ‘he doesn’t really move around much because he’s calm’. Those dogs are completely shut down through fear. The videos of static, unmoving, terrified dogs makes me literally sick to my stomach. Prong collars, choke collars, shock collars, spray collars, punishment or eyeballing the dog… these are no way to treat a dog who feels insecure.

I guess that goes without saying.

The full protocol I use for kennel guarding is available to download here

It can be adapted easily for dogs in the home where the target is a human being. If the target is another dog, this can be much more complicated and you’re going to need a specialised programme from a behaviour consultant or certified applied animal behaviourist or technician in order to help you.

It’s very important to help your dog generalise and understand that everyone who approaches has great intentions. For this, you’ll definitely need to use this protocol with a number of other people once the dog is happy about your approach. Dogs, especially reactive ones, are very in tune to small details. Even a limp or a box being carried, a hat or sunglasses can throw them off and make them unable to recognise you. My little girl Lidy when she was at the shelter, always knew it was me – she saw me coming from metres away. She ran and sat by the gate to her enclosure. But the time I turned up in wellies and a jumper instead of my usual coat and boots, she stood staring at me like ‘who the hell are you?’.

Be mindful of the fact that sometimes we smell different, we walk differently, we carry things that dogs may not realise are part of us. The rules of sevens can help a dog quickly generalise using the same approach protocol once you have helped a dog get over its fear or aggression on approach.

- Seven approaches carrying or wearing different items e.g. a large bag, a box, a coat, glasses, tinted glasses, a hat, an umbrella

- Seven approaches by similar people to you e.g. similar age and height females or males

- Seven approaches by people of the same gender but older, younger, shorter or taller

- Seven approaches by people of the opposite gender

- Seven approaches by very different people including old people, those with canes or handicaps, and older teenagers

- Seven approaches by older children

- Seven approaches by younger children

You can build up to a number of people arriving at the same time or crowds etc. The idea is that everything is staged and progressive.

Dogs should face their fears and learn that they have nothing to be afraid of. But to do so in a manner that overwhelms them or floods them is not only irresponsible and dangerous, but it won’t work. You may end up with a shut-down dog, and that’s fine if that’s what your goal is (well, it’s not fine to me, but hey, I don’t expect anyone except a hardened animal hater to say they want a shut-down dog as their goal). The approach uses gradual and progressive desensitisation where a dog becomes accustomed to approaches in a staged and controlled manner. ‘Flooding’ is the term psychologists use to describe a situation in which dogs (and people) are dropped in at the deep end, hoping that they will cope. Personally, I have never seen this work and the consequences can be long-lasting and hugely damaging. Sadly, the difference between desensitisation and flooding is only one your dog can choose. If at any point the approaches are overwhelming or cause a dog to bark or growl, you are back to square one.

Still, the results are really worthwhile: a dog who learns to anticipate with neutrality or even pleasure the approach of strangers and realises that people are not mean old bald apes after all. For dogs who are suspicious of unfamiliar people or who are uncomfortable with people approaching their crate, their fence, their enclosure, their bed, their couch or their yard, this protocol is the difference between being met by 40kg of barking, jumping, lunging, growling, snarling, snapping shiny white teeth and 40kg of wags and sits.

If you’re a trainer and you’re interested in working more collaboratively and cooperatively with clients, my book Client-Centred Dog Training is on sale in ebook and paperback