Confession time. Before I knew how to stop it, I had a dog who pulled like a demon. Once, he was part of a group of four dogs I was walking that pulled me on my arse through a field of cows to see a dog at the other side. He pulled so much that it made my hands and shoulders sore. It made me really cross with him too, and I’d finish walks furious if I had to walk him on the leash the whole walk. For this reason, I’d let him off leash more than I should and I even contemplated choke chains. I didn’t get as far as thinking of prong collars, but what I wanted from my dog wasn’t what I was getting.

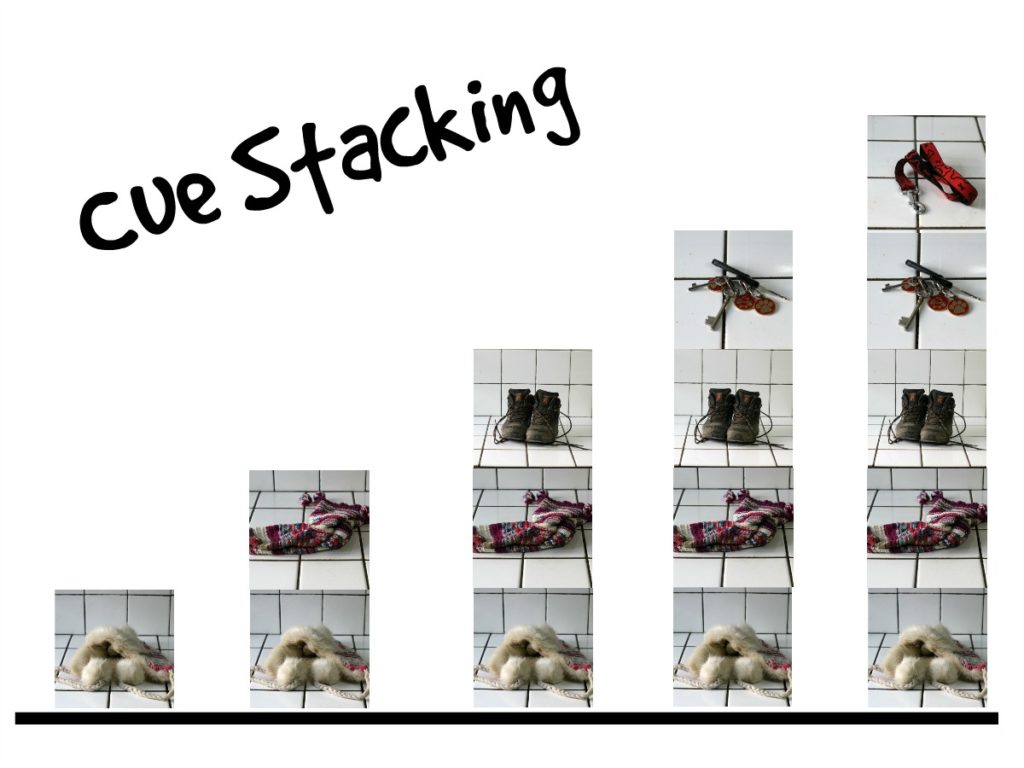

Sadly, it was all my fault too. Before I knew better, I’d clipped an extending “flexi” leash on him. I used one with my cocker spaniel and it suited us fine. But that flexi-leash taught my young pup about constant pressure and snapping to an end. It taught him he could go where he liked and to feel the constant pressure until it jerked to a stop. This is how he thought dogs walked on the leash.

Not only that, I did another bad thing. I let him off leash at 20 weeks of age for the first time. For a few weeks, it was great. He could walk without pulling and his recall was great. Until he saw a deer. And then a rabbit. His 100% recall was shot and he had to go back on the leash. But he’d got smells by then. Making a lunge to a smell, dragging me from one side to another, wrapping me up in that nasty nylon flexi-leash… so I moved to a 1 metre flat leash, which is the standard leash length. He couldn’t move anywhere and spent the whole time trying desperately to get to a scent. The leash became a punishment in itself. Not only that, but trying to walk past various dogs behind 100m of open fencing meant he too got barrier aggression. Two great reasons to pull and lunge: barrier aggression and over-excitement around scents.

And I did that horrible thing. I expected him to grow out of it. I thought that, by the time he got through his teens, he’d stop.

The dogs I’d had before either walked nicely on leash or had great recall. Molly wasn’t so great on the leash, but she had good recall (on the whole!) and she was never aggressive with other dogs. Tilly and Saffy walked nicely on the leash and good recall (unless there was a cowpat or a cyclist!) But Heston was neither 16kg of easy-to-control dog nor was he a homebody wanting to stay with the pack. No. He was an independent spirit who wanted to chase jays and crows, sparrows and starlings, deer and boar, cyclists and joggers.

While I didn’t get it right with leash walking, I did with a lot of other stuff. We negotiated destructive boredom and he had lots of other ways to burn off energy at home. Heelwork, agility and obedience training were good for him.

But a walk was a living nightmare, with me constantly on edge.

I think that’s the same for a lot of people.

I suspect that walks are the biggest point of conflict between dogs and owners. We love going for a walk with our dogs, otherwise we really wouldn’t take them. And lots of people don’t walk their dog. For 23 hours of the day, you have a great dog who you love very much, and for 1 hour a day, you have a dog that you’d surrender to a shelter. For 23 hours a day, you’re all treats and rewards. For 1 hour a day, you’re at your very worst.

Let’s face it, more people let their dog off the leash than should. I can’t tell you how many accounts of poor dog/dog greetings on a walk I read in one day. For those of us who walk our dogs on a leash, being approached by an unruly off-leash dog with zero recall is our worst nightmare. The Dog Lady posted yesterday about an off-leash incident that cued a lot of comments from owners whose dogs on leashes were attacked by dogs off-leash.

But I know why so many people walk their dogs off-leash.

On-leash, their dog is a nightmare. Off-leash, their dog’s recall may be poor, but many dogs kind of pootle about near the owner. I let Tilly, Effel, Molly, Saffy, Ralf or Amigo off leash and I know that I could walk and they’d be somewhere near me. Sure, they all have their moments where they go all Benton (remember that viral video of the dog chasing deer, much to the frustration of their owner?!) but off-leash, they’re a happy dog and I’m an owner who isn’t having my arm pulled off.

This has consequences of course. More lost dogs is one. Dogs run over is another. Dogs being self-employed on a walk is a serious side-effect. I can’t tell you the number of times Heston disappeared whilst on an off-leash walk. I can’t tell you how many times Tilly has disappeared after some distant cow-pat. But the risk of them doing so was always less than the daily pain in the arse of walking dogs on a leash

Most off-leashers seek out quiet spots away from other dogs. But you can’t predict when someone else will appear. By far most common side-effect of walking off-leash with a dog with poor recall is that if your dog sees another dog or human, they are going to approach it. I think most of these incidents end without bloodshed. The psychological trauma of repeated incidents for both dogs is enormous though. And for vets who deal with dog bites, what percentage of those happen between unfamiliar dogs where they were out on a walk with one or more of the dogs off-leash?

So why do so many people let their dogs off, knowing that their dog is a bit of an arse with others and that their dog has zero recall when confronted with other dogs?

And why do so many good people turn to choke chains, prong collars or gentle leaders to help them out in what is, quite frankly, often a daily battle? If you ask me, the daily walk is the last bastion of punishment training, the one point in a dog’s life where we feel like punishment might work even if we feel uncomfortable punishing a dog at all.

The answer to these questions is simple: walking your dog is often harder than it should be. For many of us, we feel strongly enough that we should walk our dogs but we focus too much on control rather than communication. We haven’t got good enough communication with our dog to have a fool-proof recall or a jerk-free leashed walk, so we try and control the dog instead.

Think about it, though.

You and your dog have different goals on a walk. You want to see some nice landscape, hike across the moors, take a gentle amble to the paper shop, feel good about making your dog happy, enjoy a little time with your canine friends … your dog wants to cram as much into that brief walk as they possibly can. It’s their dog time. The rest of the day, they have to refrain from doggie behaviour. No nuisance barking. No investigative chewing. No hole digging. Is it any wonder our dogs are so excited? They are FREE! But that freedom is short-lived, and they know it. Most medium-sized adult dogs are capable of a good three or four hour walk every single day. And unless you are a jobless walking health freak, there’s no way your dog is doing that.

For this reason, it becomes a really high energy moment for many dogs. I bet you any wager you care to offer that a dog who walks eleven hours a day will not be quite as excited about the prospect of a walk as your dog who gets an hour a day.

A dog’s motivation is to smell and investigate everything they can. Your motivation is… to do enough of a walk so you feel like you’ve done your bit and get home for a drink. Especially if it’s cold, windy, wet, hot, early or late.

We have other conflicting goals. We want our dogs to enjoy the walk. We don’t want automatons walking perfectly to heel, unless we are doing dog obedience or schutzhund, or unless we work in the military. We don’t want to frogmarch our dogs down the road whilst they watch us without any interest whatsoever in the world around them. By the way, if you do want this, don’t get a setter. Or a spaniel. Or a terrier. Get a shepherd. But don’t get a super-smart shepherd like a Malinois or an Australian shepherd. Get a low-maintenance German shepherd or a rottweiler. They’re more likely to see their walk as impromptu bodyguarding. They might bark at cars and grumble at passers-by if you’ve not taught them right, but they like to walk with you. It’s their body guarding job. Getting a good heel walk out of a shepherd isn’t hard. Loose-leash with a socialised shepherd is easy. Getting one out of a hound can take the most patience you’ve ever had.

Our personal goals are incompatible. Most of us want a happy medium between dogs who use what leash they have to go and smell stuff, but dogs who don’t lunge and jerk the leash. We don’t want frogmarching, but we don’t want the dog to walk us. It can be really hard for a dog to work out that some sniffing is okay but pull-sniffing is not.

Clicker training can certainly work. Watch Dr Sophia Yin or Emily Larlham teaching young dogs to walk to heel with a treat bag and a clicker, and you’ll no doubt think it’s a miracle. Their methods are perfect for young dogs who haven’t yet learned about all the other rewarding stuff they might find on a walk if only they lead you and not the other way around.

But clicker training to get a good on-leash walk with an adult dog can be really frustrating and doesn’t always work, even with minimal distraction.

I couldn’t see why clicker training wasn’t working for my puller. My clicker-trained dog who can perform a perfect peekaboo and can jump over my back, spin and twist through my legs like a slalom skier can walk to heel perfectly like an arena show dog…

And then he catches a smell and yanks me to the other side of the road.

No amount of ham, chicken skin, turkey, beef or duck is going to bring him back to me when he has caught a smell.

The fact is that once you have a dog who has learned that there are many, many more fun things on a walk than you can ever provide, you’re going to have a battle bringing it back to non-yanky, non-pully walking. How can a piece of chicken skin compete with the smell of dead badger?

For Heston, it just didn’t.

Funnily enough, it was a video about prong collars that got me thinking. The trainer kept explaining how the prong collar was a communication tool. I disagree. It’s a control tool. Sure, it communicates, but it does so with the appalling ability to shout so loud it’s like a Sergeant Major screaming in your face. It says, “you are under my control” to the dog. The dog gets to say nothing in return. That’s not communication.

A leash is a method of communicating with our dogs. It should tell them the speed we’re walking at, and the direction. Most humans are fairly predictable. We walk rather than running, and we go forward, the way our feet are facing. Sounds dumb, I know. But this isn’t always clear communication to a dog.

Not only that, dogs don’t walk like us. Most don’t walk at all. Walking’s what you do as a dog when you’re completely worn out and someone is coaxing you, or if you’re in trouble. Dogs trot. Watch your dog’s natural gait and they trot. Sometimes they run. Sometimes they gallop. But dogs don’t walk, not often. Effel lopes along. Tilly scurries. Amigo trots. Heston rushes.

And we humans tend to walk or run at a steady pace. Go run a marathon and you’ll see all the pace setters. Run a 6-minute mile? Run with the 6-minute pacer. What we don’t do is run and stop, run and stop, run and stop, run and smell stuff, run and investigate. But that’s what dogs do on a walk. If they’re setting a pace, they trot. So walking for a dog is a thing you have to teach, a pace thing.

So there are two fundamental issues with leashes. Firstly, our dogs don’t understand what we’re communicating mainly because a leash is silent and you only know it’s “talking” when you’re at the end of it. Secondly, how a dog walks and how a person walks are two very different things. What we need to teach is not how to realise they’ve got to the end of the line, whether that’s a metre or forty metres, but how to walk.

For that reason, we have two things to do. One is use our voices more and in the right way. The second is to teach dogs about speeds.

We may also have an issue with rewards and with more distracting environments for a dog.

How do you teach when the rewards you have are not as good as the rewards a dog gets for pulling you all over the path? How do you teach when the environment itself is so filled with interesting distractions that sticking a prong collar, halti, gentle leader, choke or slip leash on a dog isn’t ‘loud’ enough communication to combat the distractions?

The first thing to do is treat the walk itself as its own reward. The behaviour of going forward is rewarding in itself to a dog. On a walk, that’s what they want to do. Or zigzagging. But generally forward. Training a dog to walk loose-leash, you can use this to your advantage where chicken and ham may fail.

A walk is its own reward. For Heston, all he wants is to be on the walk. I’ve seen him spit out treats, even high value ones. He’ll take them, but he wants to walk. It’s the same with toys. He doesn’t want to play fetch or frisbee. For this reason, the best motivator is the walk itself. Moving forward is the reward. Exploring is the reward. Smelling stuff is the reward.

For this reason, one of the easiest motivators you can use with a dog on a walk is… the walk itself. It might be why your cheese is failing and your ham-scented biscuits don’t get a second look. You can see Emily from Kikopup using smell as a reward here:

Once I’ve understood that the behaviour itself is rewarding (like barking or chewing… you don’t need to teach a dog to do these on the whole!) the next thing I need to do is think about what I want from the walk. Do I want a frog-marcher, stepping alongside me, Malinois obedience style? It’s feasible if I do. You will need to do a lot of work on place-boards and turns, but you can do it. There are about forty mini-steps within an obedience walk. Any good trainer will tell you that it takes a long time to get the dog in the right position without a food lure, being able to turn on the spot keeping their front legs still and their back legs moving. Spins and twists are okay, but you need higher level stuff, like putting a placemat under your dog’s front feet and getting them to do a 360° on that. From here, you want to teach them to contact the side of your leg with the side of their body, as well as teaching the dog to circle on all kinds of different objects, including flat ones. You need to teach about eye contact too, as well as turns…. okay, so it’s feasible if you have fifty hours to train your dog to do it and lots of time to practise.

But most of us don’t want an obedience walk. Most of us just want a leisurely stroll where our dog can have a sniff from time to time without pulling us off our feet.

I don’t want to ‘control’ my dog, but I want my dog responsive to communication and I want them not to run on the leash or jerk towards a smell. When I’ve taught my dog to maintain communication during a walk through my voice signals, I won’t need leashes that control a dog: I can throw away the halti, the gentle leader, the head halter, the prong collar, the choke, the slip. I can also use longer leashes so that the dog can interact more with the environment and get the mental stimulation they crave from a walk rather than walking with me.

What I need to teach, then, is not the perfect heel or goose-step, but the perfect speed and some voice commands. If my dog is walking, they can smell as much as they like. If they’re doing the hoover-trot, where they’re simultaneously hoovering up smells and dragging you along, then this is not working. I need to take it back to a less stimulating environment where the dog is less aroused by the smells around them. I also need to teach them a cue word when I can see they’re going too fast and they’re going to get to the end of the leash. I think this is where a lot of the training videos fall short because a scrabbling, pulling dog is often trotting or running on the leash and they aren’t at all interested in food. This is where I’m going to use going forward as the reward in itself. But I still need to practise good leash behaviours like walking on the lead instead of trotting.

One of the problems I find with trying to use traditional clicker training, rewarding a dog for walking at your side and looking at you is that it only works if your rewards are more high-value than the environment, and you can spend literally months building up a ‘strong behaviour’ based on food without ever getting to the point where your food (or even play) will be more of a reward than the environment itself and your dog’s desire (and need) to interact with it. If a dog has to walk at your side and look at you (and thus interact with you rather than the environment) to get a reward, you aren’t going to win when your dog is full of energy and when the rewards for not walking at your side or looking at you are bigger than whatever treat you have to offer. Otherwise, I’ll be happy to show you Tilly’s ‘perfect’ heel walk when she knows I’ve got a pig’s ear in my pocket. But is she interacting with the environment? Not at all.

Also, there seems to be something inherently flawed about trying to teach a dog to interact in less crazy ways with the environment by rewarding them for interacting with you.

For this reason, I’m going to use the environment first as the reward, use treats/play if my dog will accept them and teach them verbal cues to tell them that they are going too slowly, too quickly or I’m going to change direction so that they can hear it coming before it does. For most leash-walking videos I see, whether prong or clicker, there’s no verbal communication at all between the dog and the walker. We’re using the leash as communication in both methods and that seems ridiculous. The dog only knows that they are out of leash when they feel the end of it which is why I think so many dogs walk at the end of the leash. If the only way to communicate that they’ve gone too far is the fact the leash jerks, then we’re failing in our desire to communicate with the dog, which is where a verbal cue is the missing link.

In the teaching world, getting your class to stop what they are doing is a similar situation. Imagine if you will a drama class in full engagement with their work, or an exam hall where you have two hundred candidates doing a paper. How do you get them to stop? You give them verbal cues. You don’t want your students constantly keeping an eye on you for some silent signal that they’re doing the right thing, or only knowing they’ve done the right thing when a buzzer goes and they get a biscuit. Dogs are capable of understanding our tone of voice, so we should use that. It seems silly to me to see gundog or working dog trainers using all kinds of aural cues like whistles and commands, and never see that in the dog walking world.

For this reason, I’m first going to teach my dog a cue to trot: “Quick, Quick, Quick”. Read Patricia McConnell’s thoughts about the effects of sound on speed and you’ll know where I’m coming from on this. Horse trainers and sled drivers use this all the time. Sounds and words equal a change in pace. Words and tone can encourage a change in pace. In fact, I’m going to teach my dog to trot on cue to “quick quick” and to walk on cue to “sloooooowww”. I’m going to teach them “stop”, too.

I promise you that people who run with their dogs have fewer problems with leash-pulling… having seen some of our great pullers at the refuge (Manix!) going for a trot with a volunteer, he doesn’t hardly need to be taught a trot because it’s his natural gait.

You don’t need to trot far, either. Ten paces following a “Quick Quick Quick!” will do. And before you go to a walk, teach your dog “Sloooooooowwww”. And use that tone. Anyone who’s had puppies knows that a “puppy, puppy, puppy!” call will bring them all to you. A “Quick Quick Quick” command is great if your dog is spending too long on a smell… and a “slooooooow” command is good if they’re trotting.

To teach these two commands, start in a safe, distraction-free zone. An empty car park if you need it. Your garden if you can. A car park is good because there’s no clear ‘forward’ direction or back, whereas a road or a path goes only in two directions, making it more predictable that you will go backwards or forwards. I’d recommend a shortish leash at this point so that they’re within your range of communication. One metre leashes are a little short and I think they can encourage pulling to get to smells, but even a three-metre leash would be too long for many dogs. Once a dog has mastered this with a two-metre leash, I move up to longer leashes and long lines when I know they’re responsive to commands further away from me.

Start this training after a walk, when your dog is not going to go mental at the sight of a leash, leave the leash on and try it then. If your dog is full of pent-up energy, you’re going to fail from the outset. And play before a walk can run the risk of amping the dog up — although I always find that my own dogs are much calmer after ten minutes of play to get that energy burst out of their system. You can use food rewards if you like to teach these two speeds. But you’re going to cue a run by saying “Quick, quick, quick”, then go at your dog’s trotting pace for a few metres. You can click and reward if you like, or give them a verbal praise. I promise you, it does not take long to teach a dog “quick, quick, quick.” You’re ‘teaching’ them to trot at their natural pace when you say. You can also build in, “Let’s go!” to show them how to turn and move in the opposite direction. The Kikopup videos show a great “Let’s go!” command.

Just remember… verbal cue AND THEN behaviour.

Then, before you stop running, say “sloooooowww” and bring the dog back to a walk. Click and reward if you like, or praise. When you slow, you’re going to walk at your own normal pace. It’s really important to reward the dog loads at this point, because this walk is hard for a dog. Before your dog gets to the end of the leash, say “stop!” and teach them to stand without moving. Teach the verbal cue “Let’s go!” to turn around and go in the opposite direction.

You’ve got to forget walking in a straight line or in one direction until your dog has learned this, frustrating as this can be. You’ve got to forget your nice little circuit, or the need to walk a kilometre or so. If you only make ten metres progress on a loose leash in an hour, that is progress enough. You can see how frustrating this might be for a dog, which is why some off-leash walking or play would be good beforehand. No point trying to reeducate your dog on how to walk properly when you’re just back from an hour of reinforcing pull-and-jerk.

Once you’ve mastered this in your garden, a closed field or an empty car park, move up to more distracting spaces. If you give a verbal cue then turn every time your dog lunges forward, every time they trot and jerk the leash, you will soon get to a point where you can use “Quick Quick Quick” as the cue to speed up (if they need it!) and “Slow” or “Stop!” to stop them getting to the end of the line. If they get to the end, I say “Too bad!” and turn in another direction.

I generally use the two-metre leashes with dogs who are in a distracting environment, three-metre ones and five-metre ones for areas where we might come to distractions like other dogs or people, and a twenty or fifty-metre long line when I’ve got one single dog on a leash in a non-distracting environment – for example, when all my other dogs are okay off-leash, but Heston’s still a bit whooo-hooo! and might do a disappearing act if he catches a smell. If I’m walking in town, it’s a two metre leash, maximum. If I’m walking a number of dogs, it’s usually two metre and three metre leashes. I actually have a carabiner attached to a short leash for Heston so that I can clip on different leashes at different moments without fumbling about.

Here’s a really good video from a BAT trainer about long line hand positions that really helped with Heston:

This is a great explanation and demonstration from Grisha Stewart that made a big difference for Heston.

As she says, it’s about walking in balance and in tune with each other. Her slow stop method was what got me thinking about teaching speed of walk and giving a cue before the stop. It’s a team exercise, but I need to make sure my dog understands that.

Teaching that you only move forward on a loose leash is vital. Teaching them to speed up and slow down on cue means that your dog can more easily predict what speed you want them to go at.

The five things that have helped most then are:

- Having the right equipment: the right leash for the right time.

- Teaching verbal cues for speed that tell a dog they are going too fast or too slow without them needing to look at me, remembering that a leash is one way of communicating with a dog, but my voice is better.

- Actively teaching on-leash walking skills when I’m not actually walking my dog and when I have no walking agenda.

- Using the environment as the reward and use forward motion as the reward for good leash manners remembering to be absolutely consistent about never letting my dog to go forward on a tight leash.

- Using long lines and Grisha Stewart’s methods of holding and handling the line to reduce pressure

You can see in the video below how Heston’s made such great progress that straight out of the car, he can walk at a loose leash. The wind’s coming in from the south carrying the scent of the wild boar from the forest a hundred metres away, so he’s a bit more distracted than usual. I also use “gentle Heston” because he knows this from a puppy, but he knows slow as well. I try to give him lots of verbal feedback about how he’s doing and he needs more at the beginning of a walk because he’s more excited. It’s a bit jerky – you’d expect that with three dogs in one hand and a camera in the other! He’s got his three metre leash on here so that he’s got some range of movement, and he does cross the road to keep an eye on the forest, though he usually walks on my right. Tilly and Effel walk to heel with no pulling, and they have great recall, which is why they’re off-leash. Amigo is partially deaf, which is why he is on-leash, and Benji is a foster, which is why he has a slip-leash and is not off leash.

Turning Heston from a dog who jerks on the leash, or trots and lunges, to a dog who gives some eye-contact during the walk and never has a tight leash has taken some time. It’s a combination of Patricia McConnell’s ideas about vocal commands, Grisha Stewart’s BAT loose-leash methods, and Emily Larlham’s clicker-training methods that has made the biggest difference for him.

Next time: how to improve your dog’s recall