Always be kind to animals,

Morning, noon and night.

For animals have feelings too,

And furthermore, they bite.

— John Gardner

Newsflash, oh people with internet… Dogs bite! They mouth, they chew, they snap, they show their teeth, they play bite, they open their mouths wide to show us their lovely pearly whites…. it’s what they do.

Where we punch, where we grab, where we snatch, where we knit, where we fiddle, where we hit, where we draw, where we tickle… dogs use their mouths. Whether it’s in anger, in excitement, in pleasure, in fun… we use our hands and they use their mouths. Using a mouth for a dog is as natural as… well… as natural as a human being using their hands.

This week, I’m exploring biting, which is different from chewing. You can find information about chewing on this post.

Normally, during a great socialisation process, puppies learn to moderate their bite strength. Just as you learn a little fine motor skill whether you’re turning out lace or colouring inside the lines, dogs learn not to hurt when they bite. Big dogs and little dogs, gentle dogs and fierce dogs… they learn to moderate their strength. By socialisation, I mean the way dogs learn to interact with animals of their own species, as well as with their humans and with other household or domesticated animals. Learning the rules of biting is often about relationships and the rules of interaction as much as it is about learning the rules of being a dog.

Using a mouth comes more naturally to some dogs, and what they use a mouth for comes more naturally too. It’s part of many dogs’ predatory sequence. Some dogs are better at withholding any mouthiness. A pointer or setter would be, quite frankly, a bag of uselessness if it went from the point or set into a full-on terrier style mauling frenzy of whatever it is they’re pointing or setting. If I had a penny for every time I’d heard people say, “Get a labrador. They have a soft mouth.” Errr…. kind of. Sometimes. Bearing in mind that labradors are implicated in more bites than any other breed of dog (because they’re one of the most popular dogs in Europe and Northern America) you must also remember that the bit of the predatory sequence you want a lab to do out in the field is ‘grab-bite’. You want them to use their mouths. You want them not to maul stuff too. But you want them to use their mouth. Just as an aside… labradors are not particularly born with a soft mouth. Many hunters of the past would be quite capable of weeding out any labs with a hard mouth, a process that doesn’t happen any more. Now, instead of some living working dogs with soft mouths and a lot of dead working dogs with hard mouths, we’ve just got dogs with mouths.

All dogs come into the world, therefore, furnished with a mouth and a desire to bite some stuff with it. Shaking, holding and dissecting are also part of that predatory sequence that dogs are born with.

It would be good if we all remembered that.

It’s not just what they bite, but also when they feel the urge to bite. Effel here, my beauceron foster dog, feels the need to bite moving stuff. Coincidence much that my much missed Malinois also felt the need to bite moving stuff?

I don’t know… it’s like they see that stuff moving and they’re all… “I just got to stop it with my mouth!”

My cocker and my griffon cross just don’t feel the same about moving things.

And Effel doesn’t just share the shepherd tradition of stalking, chasing and biting moving stuff, he shares the herding tradition of biting stuff that’s not moving to get it to move (nip to the ankles, anyone?) and also nipping things that are moving the ‘wrong’ way. In France, dogs like these are often called ‘driving’ dogs. That’s because they drive domesticated species about. They use their body and their eyes on the whole, but the mouth follows. It’s certainly not a good technique but it’s part of those fixed action patterns for herding dogs. Like collies, heelers and other shepherds, you’ve got three things that make a dog want to bite in certain circumstances. That behaviour is hard-wired into their DNA. Effel here has never met a flock of sheep. He wouldn’t know what to do with them if he did. But that behaviour manifests in a) biting the ride-on lawnmower b) nipping me if I’m not moving fast enough into the garden c) biting other dogs who get ahead of him and d) nipping smaller animals who run. It’s not a shock to hear of dogs biting inanimate moving objects (or trying to), biting running or moving things, or biting to get things to move. That behaviour is encoded in their very being, and set off by environmental factors.

But there’s another in-built behaviour that can cause a dog to bite: guarding. Whether they are guarding you, your cows, your property, your sofa, your bed, a bone, a mouldy bread roll, a stuffed Kong, a long-empty Kong or a treasured pair of their owner’s undergarments, when a dog feels under threat, you could also see that manifest in a bite, or a snap at least. Sometimes that can be a breed thing or sometimes it’s just a thing they’re born with. Stress, nervousness or territorialism are behaviours that can affect this. Again, not a surprise to get a phone call saying dogs won’t relinquish a bone, a bed, a pair of shoes or a scarf.

Don’t be surprised then if your collie nips bicycles, your malinois herds your lawnmower, your terrier shakes his chew toy or your Grand Pyrenees bites an intruder.

Despite this, breed should never, ever be an excuse for biting. If you have a heeler from strong working lines, it is your absolute obligation to socialise it wonderfully with children and never, ever let it out of your sight. If you have a shepherd, it is your obligation to socialise it around humans so that it never, ever becomes suspicious of strangers. And if you have a livestock-guarding breed, it is your duty to make sure it never, ever feels like it needs to protect you from the postman. Top-notch socialisation is crucial here. By this, I mean a gradual and careful programme of systematic desensitisation that does not over-arouse your young dog. That can definitely backfire.

That socialisation must happen early for the simple reason it is easier for them to learn as a puppy. Not impossible as an adult, but not as easy. You think I’m not working on Effel’s lawnmower biting? Not so easy with an 8-year-old dog who doesn’t have a history of learning, not even a sit or a down.

All dogs need to learn how to moderate their bite so that they don’t puncture. Great bite inhibition is vital. Puppies need socialising in two ways to acquired good bite inhibition. One is with other puppies and other adult dogs, so they can learn how not to hurt (and breeds or crossbreeds who get off on squealing victims need you more than ever to teach them play restraint around other puppies, even from 5 weeks of age). And the other way is good bite inhibition with all manner of humans, be they large or small. Again, a degree of caution is absolutely vital so that you don’t end up accidentally teaching your young dog the marvels of biting and just how much fun it is.

Another factor comes into play as well: emotions.

Like it or not, dogs are much more governed by emotional reactions than people are. If we can’t stop ourselves smashing plates in anger, or punching a wall, you can imagine how hard this is for a dog, whose brain is hard-wired to be much more instinctive and emotionally reactive than ours. Acquired bite inhibition is the only thing stopping them hurting an animal or a person when they are angry, frightened or excited. Teaching impulse control should sit alongside good socialisation.

Some people will no doubt argue that you don’t have to teach it – that it comes naturally. This is no doubt a fallacy. You can teach adult dogs to use their mouths more softly. The mouth is controlled by muscles. Dogs learn by trial and error just how much effort to put into an action. Without practice, that doesn’t happen. Just as they learn how much effort to put into a leap to get over a ditch, they can moderate the power in a muscle when they bite. My dog Heston knows just how much effort to put into a jump to get over a ditch. But he had to learn that. Once learned, you don’t have to think about it. Effel, who is not used to free-running over ditches has to take his time. He has even done a proper roly-poly into the ditch. Why is he so inept? Lack of practice. He got better as time went on.

See? Motor learning at work. One looking, going slow (as he tumbles at speed) and one who is able to do it at speed because he’s been doing it since he was young and we gradually built up all the muscles he needed to do it instinctively.

Using a mouth is a motor learning skill. That’s why a dog needs to learn how to do it before it becomes instinctive. If you don’t use it and don’t have the right opportunity to use it, chances are when you come to use those muscles, they won’t be under motor control.

Imagine learning to drive – or even changing a car. You don’t instinctively know how much pressure to put on the accelerator to move forward, which is why learner drivers kangaroo and have problems on hill starts. You learn and then it’s instinctive. Muscle memory – once acquired – is instinctive. Muscle memory, or motor learning if you prefer, is acquired through practice. In my opinion, practice is what socialisation should be.

Along with inherited behaviours, then, poor socialisation in my experience is another piece in the jigsaw of why dogs bite. If they have been isolated from other dogs too early, you may find an adult dog who has poor bite control. That’s what happened with Putchy, the little chihuahua surrendered to our shelter. 5 months old and he was a serial biter. Removed at six weeks from his family group, he never learned how to control the strength of his bite, or how to use other behaviours like a growl that prevent the necessity for a bite. Three weeks of intensive socialisation with great dogs and he’s a different dog. This also happened with Julio, removed at the same age. A beauceron cross, he would bite when excited and was surrendered for this behaviour. Sadly, with bigger dogs, teaching them soft bites can be that much harder because they can’t be trusted not to inflict a lot of damage on other dogs. Putchy got lucky.

There are plenty of hormonal and physiological reasons a dog might bite too. The common we talk about is testosterone, implicated in aggression and competition. But this can be tricky. For an aggressive male, castration can make a real difference (although testosterone is manufactured at other points in the body too) but if that aggression is driven by fear, it can make the fearfulness (and therefore the biting and aggressive behaviour) that much worse. Be really, really sure if you are castrating to sort out a biting issue that you are dealing with testosterone-led aggression. If not, you are running the risk of leaving the dog feeling even more vulnerable and under threat. Several studies support this so if you have a dog biting out of aggression rather than play or over-stimulation, it is something to really discuss carefully with your vet.

“With various types of aggressive behavior, including aggression toward human family members, castration may be effective in decreasing aggression in some dogs, but fewer than a third can be expected to have marked improvement.”

Neilson et al., 1997

Maternal hormones can also be involved. Females with a litter may be more aggressive around other dogs. Oestrogen and progesterone levels can be implicated too. There is some evidence that sterilised females may bite more frequently than those who are not sterilised, no doubt related to more long-lasting changes in hormones.

And it can be chemical. A surge of adrenaline doesn’t just come from fight-or-flight hormones and neurotransmitters, but also from excitement or over-stimulation. If your dog’s got a lot of adrenaline coursing around their system, it can be much more likely that a bite will happen. That can happen in times when they’re being exercised. It can also happen when they’re stressed or excited.

Biting can also cause a pleasure response and therefore become a learned behaviour. I did it. It felt good. I’ll do it again. Or I did it. It worked. I’ll do it again. Like one of the shepherd females at the refuge. When she is over-stimulated, when there are too many people around, when there are cats moving and dogs approaching, men with wheelbarrows, she is much more likely to jump and bite. She NEVER does this when she is just trotting along besides me doing a happy sit-and-focus. She did it twice yesterday. Once when we’d been sitting and waiting for two dogs to go past. Once when we got back into the shelter and we were cornered by three people. That is entirely related to shots of adrenaline and norepinephrine, which cause her a manners hijack. Couple that with being a malinois and having had little training or socialisation and every single time she does it, it feels MIGHTY FINE and gets rid of all that chemical energy, so she does it again. But for another dog who doesn’t like dogs in her space, she has learned that if she bites dogs and gets her attack in first, it solves her problems superbly.

Biting can be done for pleasure, like the girl above, or it can be done in rage. It can happen when dogs are anxious or panicking too. Biting can be a resource-guarding habit, and you have no way of helping your dog decide what an appropriate resource for them to guard is.

Through all of this, we must not forget that pain is a big factor in why dogs bite. The very first stop that you should make if your dog’s bite behaviour has changed is the vet. But make sure you’ve prepared your dog for a muzzle! Being manipulated or constrained can also be the reason for a nasty nip. You wouldn’t handle a scared cat without expecting confrontation, but people expect dogs to be in some way more docile.

I’ve actually known more little dogs bite than big ones. We feel that obligation with big dogs and we can’t manipulate them in the same way. We don’t try to wrestle them into car boots or carry containers. When our big dog grumbles, we don’t force them to do stuff, which we then might be tempted to force a smaller dog to do. When a dachshund was guarding a bed, the owners tried to lift the dog out and the dog bit them. If it had been a great Dane, there wouldn’t have been a choice but to find ways that didn’t involve hands-on.

So the first step in treating bite behaviour is to know what’s behind it. Then you can act accordingly. That might involve putting a feeding mum in her own space with her babies. It might involve teaching a dog in pain about consent and how to let you know in appropriate ways that he is no longer feeling comfortable. It might involve remedial socialisation for a young dog removed too early from the pack, or teaching an older dog how to manage their excitement.

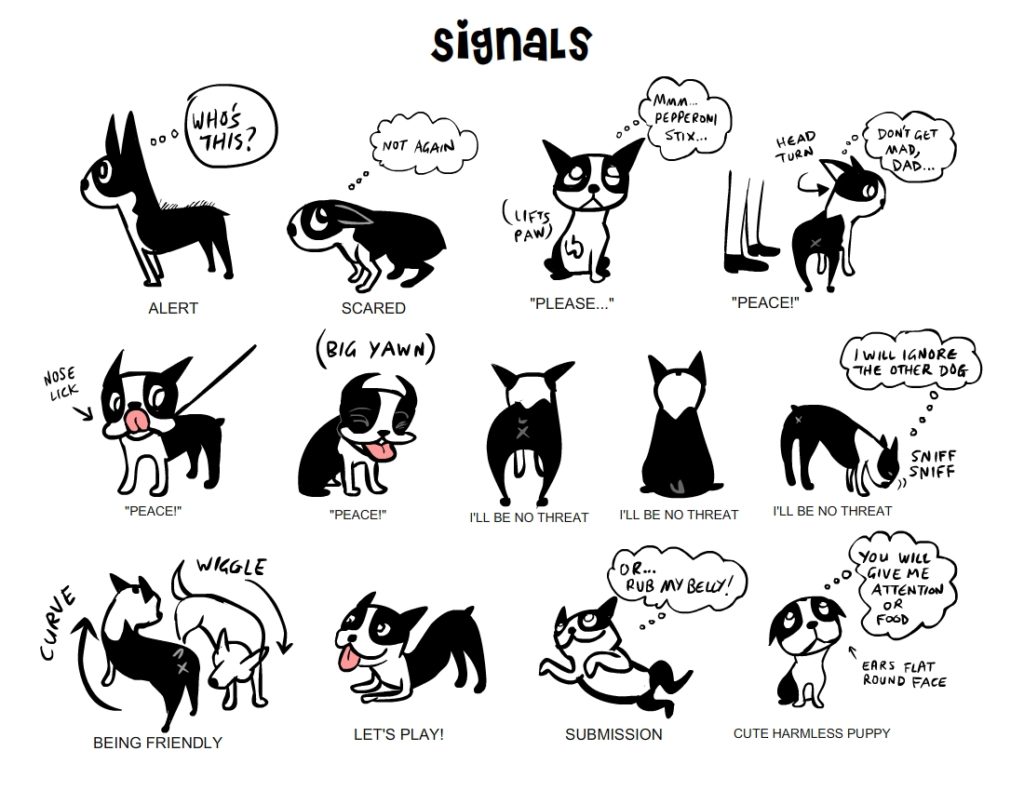

One thing that is very effective no matter what the cause is, is knowing the signs your dog is giving you that precede a bite. This great, simple guide from Lili Chin at Doggie Drawings

For many dogs who nip, it’s primarily a grab-bite instinct that appears each time they’re excited. These are often dogs who have relatively good bite pressure normally. For instance, my current nippy Miss at the shelter has great manners and would never bite when she is not over-aroused. Mr Nippy the labrador has a generally hard mouth and poor manners, plus he is demanding when over-excited. The nips or mouthiness happen when the dog is over-stimulated.

For those things, it’s really important to keep them below that excitement threshold. That means you need to manage their environment. Trigger stacking is not all about fear or aggression. It can be about excitement too. Think of how your dog is if you have sausages for lunch and if they see their leash. Think of them at their three most unmanageably excitable moments and then think of those things coming together. Adrenaline isn’t just about fear and aggression. It’s a reaction when we are excited too. Anticipation, arousal and pleasure are all emotions that start a dog off on a complex chemical journey that can end in exuberant behaviour (like when your dog gets the zoomies or the mads, and races around the garden in a frantic burst) or even a bite.

So the first thing to do with a mouthy dog is to think about what triggers it and when. Bitey Miss can’t handle a walk, cats, other dogs and people all at the same time. Three out of four she can manage. But four is too much. Put a wheelbarrow in there and you have a perfect storm of conditions for a nip. Bitey Mr can’t handle the excitement of a walk coupled with the stress of 100 barking dogs and the anticipation of the treats you most certainly have in your pocket. Bring both of them back down from that excitement and you’ve got two dogs who are either really docile or relatively non-grabby. What is very interesting however is that the majority of dogs who nip in over-stimulation are also dogs who get excited by inappropriate handling. Sorry. That sounds rude. But biting in excitement is a behaviour that is deeply related to dopamine in dogs. It’s heavily implicated in the basal ganglia in the brain, which is not only connected to reward learning (so when something feels good, we do it again and again and again, she says, eating another biscuit… ) but also related to voluntary motor control and action selection (which is why I can’t stop myself eating another biscuit even if I am full and I’ve had enough and I’m reasoning with myself!) For some dogs, the level of dopamine in the system is no less than the effect of cocaine on a person. Decision making is poor, rational learning is impossible, and we’re stuck in an addictive loop. The nucleus accumbens is implicated in impulsivity, reward and motivation too. For some dogs that’s what mouthing and biting is: a biological impulse that feels bloody good. And the more they do it, the more they’re chasing the feeling.

I think for many dogs, the sight of a hand or arm moving can be a precursor to other things. For herding dogs, it’s just a limb like any other. Also, our hands move faster than our other bits. Legs are pretty slow in comparison. Those lovely fingers might as well be dancing targets. I think that for many dogs who do get over-excited and then bite, they need a lot of remedial socialisation with hands. You literally cannot touch these dogs face first. Jean Donaldson in her book Mine! has a good programme for touch desensitisation. For Bitey Miss, you can pet her so long. She lies on her back for a tummy tickle, or sits for a chest rub. But when she gets excited, it’s the hands or feet that set her off. Desensitising her around hands is a crucial part of her ongoing treatment. This has also been true of Bitey Senior. He enjoys a side-on back rub and rump rub, but we’re not past shoulder rubs. Head touches are the stuff of snappiness, especially if that happens face-to-face. Bitey Junior is another one who gets over-stimulated when hands arrive. Possibly this is a throwback to poor socialisation with humans for all three, but breed is a definite part of it as well. Desensitising a dog to hands and their movement is essential.

And what about dogs with poor food manners or treat reception?

Handfeeding is your saving grace here. Handfeed every single morsel that passes the dog’s mouth and your dog will soon realise that a hard mouth means food stops, and a gentle mouth means golloping as much of it as they like.

Just as you’d desensitise a puppy to hands to stop mouthing and nipping, so you need to with an adult dog. Yes, teeth and all. For this, I’d recommend well-fitting gloves or even gauntlets if they have a very hard mouth. To be fair, I did it without gloves with Bitey Senior who has a super-hard bite, but I must have been mental that day. To start the dog must be in a place of real calm. I mean super calm. And relatively full, if not completely. Start with a really, really crappy, massive, low-value treat – something one step up from cardboard, especially if they are food-motivated. A huge thing. Bear in mind that a lot of dogs have poor food manners because they haven’t been hand-fed and if they have a long nose, they have no idea where your hand is or where the treat is. Sometimes it’s just like grabbing in the dark for them. So a huge treat at least gets them in the right ballpark while they learn. Think of someone learning to throw darts at a board. I mean you want to use a really, really big board if it’s important they hit it. For Bitey Junior today, I was using big old treats that taste of flour. Massive ones. He isn’t overstimulated around them and I’m less likely to get a snap. I started this way with Bitey Senior, just with HUGE chews. As you move on, you can use higher-value treats and smaller objects, just as you would with a puppy. So they miss from time to time as a puppy, and you say “Ow!” and they learn… not something you can do with an adult mali who is food-obsessed and has a snappy bite. They don’t call them Maligators for nothing.

With adult dogs, there’s no reason you can’t do the same as you do with puppies… just with more care. You absolutely have to have a dog that is at its calmest for this bit. If that means putting it on a really good lead and working with a partner so that you can move away if necessary, do it (just be mindful of redirected frustration bites coming back on your partner!)

This video from Kikopup is essentially the same programme I use with mouthy, bitey dogs who’ve not learned a soft mouth with humans yet. I’m just much more careful and take it much more slowly. What Emily says about teaching an alternate response is very possible. You may fear using the closed fist approach to “no hand mugging” but I actually find snack-snappy dogs function better when your hand is super-slow, when they see the fist is closed and they can’t get the treat. You can almost push the treat into their mouth with a flat hand. Bizarre I know. What you want to do is take your hand away completely, yet your snatching your hand away is what causes their snapping on the treat. I would not try this at all with any dog who has a very hard bite. I still don’t do it with Bitey Senior, though it worked with Bitey Junior well this afternoon. You absolutely CAN do the reach and touch with a fully-grown Dally who snaps at hands, just take it really, really, really slowly and use huge, low-value treats when they are calm. You can also use games like ‘It’s Yer Choice’ by Susan Garrett, which I find very helpful for dogs with hard mouths.

To my mind, mouthiness, nipping and biting can be some of the most frightening things about a dog. It is not impossible to bring them back under control, though it takes longer with an adult dog and they may never get it to an instinctive part of motor memory. Although some people feel that they could never trust a dog with a hard mouth or poor control over impulsivity, I think it would do us all good to remember that dogs bite. I’d rather work with a hard-mouth dog whose bite I’m familiar with than a dog who has never bitten – one has a bite pattern I’m familiar with, and the other is a completely unknown quantity. Knowing that most biting is either a reaction to pain, a result of poor handling or as a consequence of over-excitement and poor impulse control is a good way to stop your dog being put into a position where biting is the only option. If we all kept our hands to ourselves when meeting unfamiliar dogs, it’d do both species the world of good.

Next time, a quick look at what you can do if your dog growls and grumbles when they’re guarding: how to handle a resource guarder.