About twenty years ago, I was part of a team who worked on internet safety for our 13-year-olds in school. We pushed several messages about bias and motivation, but we had no idea at the time that the internet, thanks to social media and Google rankings, would become a massive popularity contest.

Let me clarify my position. I’ve got two businesses. Both of them do really well on social media and on Google rankings (thank you!) and I’m regularly on the first page of Google rankings despite not paying for posts. I spend a good part of my week working out how to maximise my content, about keywords, about SEO and about how to manage a social media presence. I’ve had posts shared over 200,000 times and posts seen over 8 million times. That’s pretty tremendous for someone who has never paid for content.

I sincerely believe that you can rank highly with superior content. But I also know that you can manipulate rankings either through money or through the methods known as ‘clickbait’. Politicians, opinions and popularity rise and fall on the tides of such methods.

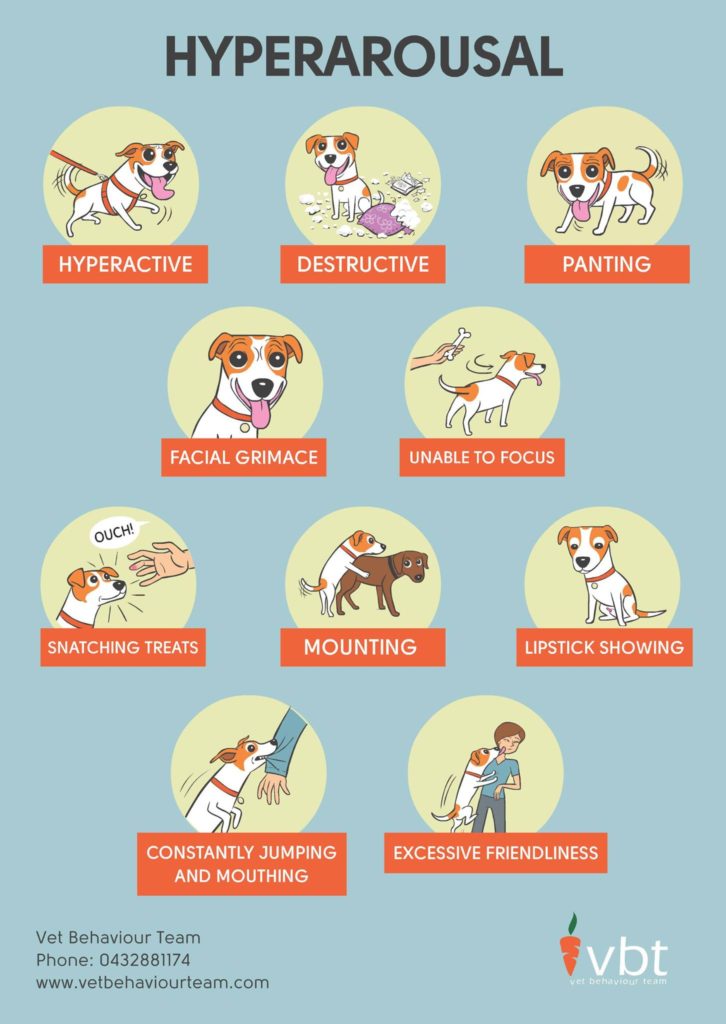

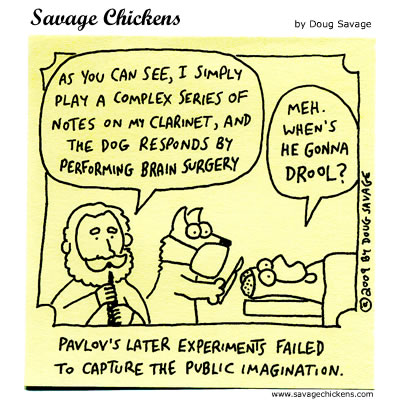

Sadly, clickbait is a rising trend as dog trainers fight for clients, and, more worryingly, their messages are potentially damaging for many of our dogs. But it’s not just people using unethical marketing to attract business. It’s also noisy, opinionated people who believe blindly in a food regime, in a health regime, in a supplement, in a training method.

I’m aware that puts me on the Donald Trump side of ‘Fake News!’, decrying everything I don’t believe in as phony, sham or manipulative.

It’s not just about calling people out though, especially if their views don’t support your own. It’s not just dismissing people who don’t think what you do. It’s about remembering their biases, their credentials and their purpose for posting before making a decision about the validity of what they are saying.

Time we step back.

Back to those twenty-year-old questions:

- What do we know about the person who posted this?

- What’s their bias?

- What’s their purpose in posting?

I try to bring this to everything I read. It’s fine to read things that are biased as long as you recognise that bias. It’s fine to read things on the internet as long as you know a little about the person posting and their credentials. It’s fine to take on their messages when you’ve considered why they are posting. I seek out alternative views and try to keep an open mind – all time aware that challenging your beliefs can actually make your views more stubborn and persistent rather than open to fresh data.

Back to the most fundamental of those questions: what is their purpose for posting?

For some people their only purpose for posting is marketing. They’re fishing for sales. They share, not because they want ‘the truth’ out there, but because they want posts that drive traffic to their websites that drive traffic to their phone that drives traffic to their door that puts money in their bank account.

There are two ways you can do that: honestly, with authenticity, or dishonestly.

Authentic people are honest about their standpoint, their views and their purpose. Dishonest people aren’t. It’s fairly cut and dry.

I would much rather ten authentic people whose views completely contradict my own. I would rather the honesty of alternatives. It’s the deceit in marketing that I can’t stand.

That’s especially important where other living beings are concerned.

What concerns me the most are people who don’t put themselves up to scrutiny, who disguise their beliefs and values in order to get business by any means necessary, and who then deliberately write blog posts that are designed to get people sharing.

One of those dangerous trends comes from ‘pet health sites’ who aren’t clear that a) they aren’t always certified vets even if they have a title to their name b) they make up their ‘statistics’ and lie or c) they have a vested business interest in what they’re promoting, usually financial.

Not only that, for every fake story they put out, every article that isn’t rooted in reality, it damages the whole field of holistic and alternative medicine. If alternative medicine wants to shake off its snake oil and woo-woo reputation, several of those big ‘pet health’ sites need to take a good look at themselves. Anyone who would willingly damage their own field makes me question their motivation. If you would willingly spread misinformation that could seriously damage the health of a pet and also the field in which you practise, I’m sorry but you don’t deserve to have any credibility at all.

Any online vet, for instance, that exclusively promotes one diet or another when it wouldn’t be appropriate for the pet, is not a vet that I can have faith in. If that site is populated by ‘cute’ stories of dogs playing with birds or video compilations alongside scaremongering, I can’t get away from the fact that some high-ranking sites have an agenda that should impact how I read their (FAKE!) news.

We always need a healthy degree of skepticism where things are promoted or discouraged that take one side or another where medicine is concerned. I trust my vets implicitly but I’m not afraid to ask questions and they know me well enough to know they can give me an answer. But when you go to vet conferences, as I have been privileged to do from time to time, there are things that most vets do, things that all vets do, and things that divide the room. Mention precocious sterilisation, for instance, and you’ll divide the room. Mention methods of anaethesia or post-surgical care, and you’ll divide the room. Those are three simple everyday topics where the arguments can last long, long into the night or where many vets keep their opinions to themselves because they know they’ll be forever damned by their peers for revealing their standpoint. And, as most vets will agree, whether you fall into one camp or another is not an ‘always’ kind of thing.

As always, ‘it depends’.

They make their decisions on a case-by-case basis, not on a one-size-fits-all.

But just because they prefer one thing over another doesn’t mean they are wrong.

But it does make me worry when popular pet health sites promote one thing to the exclusivity of others. Not least because they don’t know our pet.

We should trust OUR vets enough to have a conversation. Not online vets who have never met our animal. If you don’t trust your vet, shop around. If the only vet you find you can trust is one online that you’ve never met, then it’s time to ask some questions about why that it is. Believe me, the answer is not because all your local vets are inept and the online ones are the only ones to tell the truth, I promise you.

It’s a good idea to go into conversations asking for all the pros, all the cons and then make your mind up based on who you trust and knowing them instinctively. I know which of the vets I regularly see are worrywarts, who are the best surgeons, who are great technicians, who are solid on dentistry or osteopathy, who can be dismissive and who are overly cautious. We need to trust our vets and get to know them. It’s a reciprocal relationship. They need to know which of us are worrywarts, which of us hand our dogs sneaky sugary treats, which of us have problems exercising our animals, which of us follow advice, who needs an explanation and who doesn’t.

I particularly love my vet surgery because when I go in with my particularly catastrophic “it’s liver failure/cancer/peritonitis/tick fever”, I never leave without feeling completely sure that it isn’t.

If you don’t trust your vet to ask “Are you absolutely sure it’s not osteosarcoma as I googled these symptoms, even though I know that is dumb, and that’s what it said”, then you need to find a different vet.

By all means get a second opinion, but don’t fall into the conspiracy trap of thinking that an online expert is right and the rest of the medical world are wrong.

Let’s talk one of those things regularly posted on ‘woo woo’ sites: vaccinations.

Someone posted an article from a ‘holistic’ vet site about the dangers of vaccinations and even the pointlessness of titre testing. Basically, it was advocating doing nothing.

I don’t know if you’ve ever seen a dog die of parvovirus. I have. In fact, it’s more regular than you’d realise in a world where there are puppy shows, kennels and pounds. Distemper, not so much, not where I live. I’ve never seen rabies. But parvovirus, yes. Our main problem at the pound and shelter where I am a trustee is unvaccinated dogs. So much so that we vaccinate on the first day of arrival and keep dogs isolated as long as possible to minimise risks. It’s a small number of newly arrived dogs who contract parvovirus – around 1% – and a smaller number still who die from it – but it’s a number nonetheless. We have not had a dog die of parvovirus who has had the second vaccination. Those are our statistics.

So it makes me skeptical when unqualified and uneducated people discuss the efficacy of the vaccine on Facebook, and also when they discuss not vaccinating at all, guided by advice from a vet who is a) not aware of local vectors b) not a vet for your pet c) has never met your pet d) has a very good income from the adverts and products on their website.

When it comes to vaccinations, I absolutely trust my vet.

I remember the names of every single one of those dogs who have died of parvovirus.

I remember who spent 11 days on a drip.

I remember who nearly died.

But the general public, who don’t get the health and sanitation figures for animals in their region, don’t see those names, don’t see those numbers and don’t realise why it’s so infuriating to see clickbait shared time and time again that is just plain wrong. Nobody shares clickbait that says how efficient the vaccines are, and how vaccinating against disease has all but eradicated it in some parts of the world.

Now we can wring our hands after the dog has died, wailing and beating our chests about viruses and diseases that can take our dogs away, or we can have an informed discussion with our vet. We need to stop thinking that they’re all out to become millionaires on the back of our gross stupidity or that they are too ignorant to become as informed as we are – or at least we think we are, having read biased and inflammatory articles on dodgy sites that support our nagging hesitations. When I took Amigo last year to the vet for his jabs, she advised against his yearly vaccinations and he just had the (perennially controversial) leptospirosis vaccination. Having had a stroke, I wondered if she thought it would interfere with his health or if she was just telling me politely not to waste money on a dog who probably wouldn’t live out the year… so I asked her. She explained why and I agreed, so that was that.

For my dog Heston, he’s still a young guy. He comes with me often to the shelter. He has his yearly vaccinations and he always will until he’s an old dude – because I put him at high-risk with what I do.

That’s what makes me angry – people say ‘my dogs don’t go to kennels, I don’t travel, I don’t take them to dog shows, I don’t walk them with other dogs…’

Sadly, you don’t live in as safe a world as you think you do, where disease is concerned.

I sure as hell hope that nobody ever leaves their gate open or that their dog never, ever escapes and ends up in the pound, or never comes in contact with parvo or distemper when they do need to take their dog to the vet… because they’re precisely the kind of dog who will contract the disease.

But if you have a really low-risk lifestyle and a low-risk dog, I can see why you might want to have a conversation with your vet. I’m not going to tell you whether you should or shouldn’t vaccinate. That’s a conversation to have with your vet.

In fact, there are hundreds and hundreds of things I like to ask my vet. My poor vet. Which chews are okay and which cause slab fractures? Have you ever seen a dog with a tongue stuck in a chew toy? Do dogs really die from eating chocolate? Is agility okay for my shepherd? What about frisbee? What exercise can I do with my dog who had a vestibular event? Can I give melatonin and valerian to my dog who has dementia? Is this food causing colitis?

I want my dogs to live long, healthy lives, and following every fad shared in kooky websites may cause more problems than they solve.

That is especially true as certain popular pet health sites are happy to run with Daily Mail style headlines about “this food is KILLING our pets”, “this pet health bombshell that everyone is ignoring that is KILLING our pets”, “This bad habit is KILLING our pets”. But because the good (eg don’t smoke around your dog – passive smoking is not good for your pets) is mixed up with the sensational (feeding X, Y or Z is killing our dogs) you end up either ignoring the good stuff because you are suspicious of everything on the site, or believing the sensational.

But pet health marketers unfortunately take advantage of our feelings, which is why we need an added layer of skepticism.

At the same time, I’m conscious that there are more things in heaven and earth than science has got round to testing yet. And I’m also conscious that we don’t know everything. If it won’t hurt and it might help, then it’s worth a look. I’m a fan of Rescue Remedy sometimes. No idea why it works – it just seems to with some dogs. Melatonin worked with Amigo, and so did valerian.

Actually, what helped more with his night-time wanderings was me taking them.

His wandering wasn’t upsetting anyone except me.

I give my dogs glucosamine and chondroitin supplements even though I know that glucosamine only had success in lab tests but not outside the lab in real life and chondrotin is practically pointless from an academic point of view. I use MSM and GLM supplements for arthritis as they seemed to give Tobby more mobility than when he didn’t have them, or when he was on anti-inflammatories alone. GLM has done well in some small tests and so has MSM.

I’m really pleased to have found a vet who is happy to discuss these things and also to recommend them if she thinks they might work.

I’m glad that when Ralf got in a fight with a badger, I walked out with arnica for his bruises, some anti-inflammatories for his fat lip and cauliflower ear, and some antibiotics against the yucky stuff a badger might have transmitted through a bloody open-wound contact fight. I wish I could have done the same for the badger. But that combination of proven medicine and great natural remedies is what I like. For me, that is truly ‘holistic’ medicine.

So it’s not to say I need everything to be governed by what I’ve seen, like the efficacy of particular vaccines. But neither do I jump on all trends. Given the recommendations on Facebook I got for my new foster who has a range of ailments, she’d be rattling with woo-woo medicines. I’ve got to sift and appraise from my friends’ experiences, but Facebook doesn’t have the knowledge that my vet does. When I read about a medicine or a treatment, I try to focus on who wrote it, their bias and their purpose. Once I’ve taken off my own blinkers, I can do better for my dogs.

After all, all of these things we do, it’s because we love our dogs and we want them to live as long as possible.

That said, we shouldn’t ever let our heart rule our heads when it comes to diet or medicine. If I see ‘products’ and ‘shop’ on an article that’s supposedly about canine health, I’ll take everything with a large pinch of very unhealthy salt. I want sponsors to be clear that they are sponsors, and if I suspect a whiff of dishonesty from ‘natural’ sites, I’m off to look for more reliable stuff. If an ‘information’ site asks me to subscribe, I’m out of there. Why on earth would they want me to subscribe unless to sell me something? I don’t want to see ‘web entrepreneur’ alongside a biography of a ‘health practitioner’ and I’m fond of visiting sites such as Skeptvet to check out the other side of the argument. And I’m aware too that it is their job to be skeptical about stuff. That is their bias.

If in doubt, look at the front page of the site.

Does it state in the headline what it’s about, or is it just ‘This THING will KILL your pet’ and you have to click to find out what?

Does it have a ‘shop’ button? This for me is the big giveaway.

Does it have a load of sponsors down the side?

Does it ask you to sign up now?

Does it have pop-up boxes to get you to subscribe?

ALL good signs that the person producing the website is making a bit of a living (or a very good living) from marketing.

Sadly, because they do not know our pets, because they do not have a whole history, because they do not know us, any online vet or health site that gives advice should be read with a healthy amount of skepticism. Any zealot who doesn’t mitigate their own advice with ‘go and see your own vet’ is lucky not to face lawsuits more frequently. And it goes without saying that if the advice is on a forum or Facebook, take it with a huge pinch of salt. Do your research if it sounds interesting. I’m in a few great groups for canine dementia, for vestibular disease and for degenerative myelopathy, and they give me ideas of things to discuss with my vet, but they certainly don’t replace my vet and they never will. Even if they were Mr Super Vet himself on Facebook giving me advice about vet care, I’d wonder why he was so happy to dole out free advice – other than the stuff that is generally accepted, like looking after your dog’s teeth, keeping their ears clean or the problems short-nosed dog breeds can face. If I follow vets on Facebook, I’m looking for photos of their pets, photos of their clients’ pets, even photos of operations, some good advice for all dogs and some posts about interesting animal facts. I’m not looking for a zealot and I’m not looking for them to diagnose and treat my pet online.

But medicine is not the only place where controversial sites publish clickbait. Sadly, this is infecting behavioural advice for dogs too. Next week, I’ll look at some of the FAKE NEWS! from the behaviour world that is potentially very damaging for our dogs.