RES·IL·I·ENCE : the ability to become healthy, happy or strong again after a setback, illness or other problem; the capacity to recover from difficulties.

No matter how we try to keep our dogs safe, life often has other plans.

Only a few months ago, for example, another volunteer and I were the first cars on site at a motorway crash, having watched it all happen in surreal slow motion. The worst was watching two dogs come stumbling out of the back of the van and into the path of speeding wagons. The van they were in had rolled, and during the impact, the back door had broken. Luckily, despite the speeds involved and the damage, both the dogs and the driver were okay.

Physically, at least.

A fractured skull, but no other broken bones. It could have been so much worse.

Resilience is how we cope with the crap that life throws at us. Like car crashes in the driving rain on a Friday night.

It’s about how quickly we bounce back. It’s how we cope and how we respond to things. Resilience, from a biological perspective, is how quickly we move back from fight-flight modes into homeostasis. You know… how quickly we go from fight or flight to rest and digest, feed and breed. Resilience, as far as your body is concerned, is how quickly you go from “Incoming!!!!” to “When’s lunch again?”

You can see resilience in action.

This is Lidy. Lidy, when I first met her, was a hot pink mess of 11-month old whirling dervish snaggle-toothed dragon. Her resilience was poor and she was permanently in fight-or-flight mode. She was super-sensitive to flooding her sink and trigger stacked to the max. She never really recovered from each and every episode.

She was on a “Bite First – Ask Questions Later” protocol.

We’ve come a long way, Lidy and I. To the point where, when an off-lead mental, barky over-aroused spaniel ran full pelt at us and Lidy coped. Within 30 seconds, she was rooting in the bushes.

It did NOT take me 30 seconds to recover, let me tell you. I still have flashbacks and nightmares.

Or when the shelter director’s chi-chi, Kiki (formerly known as ‘Killer’) ran up to us to tell us in his best Mexican that he didn’t appreciate her, Lidy recovered in less than 30 seconds. Kiki still had a barking head attached to his snack-sized body.

So resilience has a physiological timer we can watch for that manifests in behaviours. How long does it take us to go from Tarantino Film Extra to Normal Services Are Resumed – Nothing To See – Here?

But it’s not about being 100% laidback 100% of the time. There are ‘bombproof’ dogs – I’m sure you know one or two – that can cope with every single thing that happens. I’ve seen dogs thrown from windows, thrown out of cars, hit by cars, shot… dogs who cope with things you and I would find ourselves a quivering wreck over. Resilience doesn’t have to be this. You meet a dog called Lucky and I bet you’re looking at a resilience role-model. In fact, I’d largely argue that if you don’t have a bomb-proofer to start with, you’ll probably never get one. You’re born Lucky or you’re not so Lucky.

What you may get is a dog whose reactions are milder, less frequent or shorter – a dog who takes 30 seconds to bounce back rather than 3 days – when they’ve learned to be more resilient.

But I don’t think anyone would promise you a bombproof dog if that’s not what you’ve got already.

Resilience can be preventative. It can be built. We can build it in young puppies to inoculate them against stuff happening in life. We call that socialisation and habituation. We can build on the genes that we get, or those we don’t, to help our puppies prepare for the world.

There are lots of really great Puppy Culture groups that will help you with that. There are plenty of great books, like Steve Mann’s Easy Peasy Puppy Squeezy, Puppy Start Right by Kenneth and Debbie Martin, or Life Skills for Puppies by Daniel Mills and Helen Zulch. There are online courses too. You can also find great puppy classes, but be careful it’s not just a puppy maul – you could end up killing off your young dog’s resilience before you can blink.

You can – and I’d argue that you should – continue to build on resilience through life. Make novelty fun, build in routines to cope with life’s unexpected spaniels and chihuahuas, bicycles and car horns. Once, I walked with Heston through a Venetian carnival by accident. Capes, masks, flappy things, music, feathers, costumes and instead of having flashbacks about the time a guy with a plague doctor mask bent to pet him, it just became one of those things in life that contribute to your resilience in the future. When novelty is safe and dogs have choice whether to engage or not, life’s scary stuff can be a learning experience. To steal from Ken Ramirez, instead of it being a tornado, the animals in your life will just be thinking, “hmmm…. now what are the naked apes up to today?”

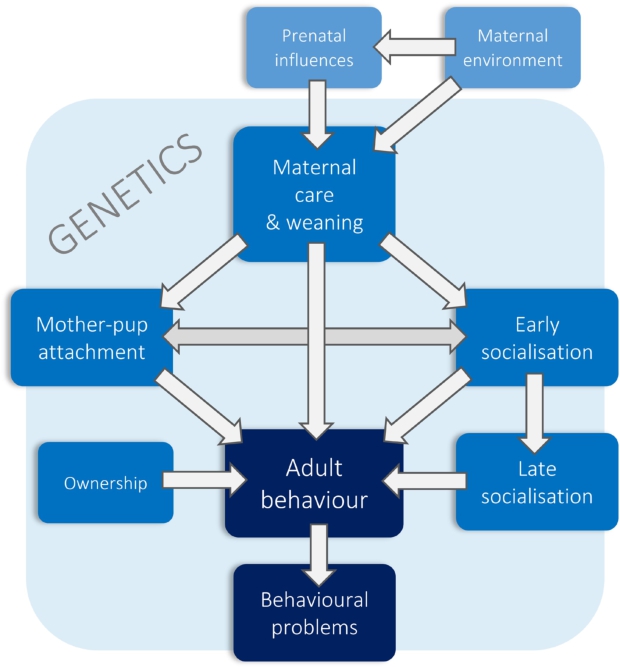

Whilst resilience can be preventative, it can also be well and truly buggered up by some of the things in the big old jigsaw puzzle that contributes to the adult.

As you can tell from this amazing “soup” of factors, there are so many things that influence the adult our dogs become and their resilience to stress that it can be difficult to pull one from another.

The toughest cases for me are those dogs who live in a semi-permanent state of stress. Bad genetics, lack of resilience in both the maternal & paternal line, exposure to in utero cortisol, birth order, even things like the mother’s feeding position all contribute to a lack of resilience.

Animal behaviourist Patricia McConnell says resilience is on a scale, like 1 – 10. Some dogs are born in life with the potential to only ever be a 3 or a 4. They are never going to be cadaver dogs, bomb detection dogs, SAR dogs, sniffer dogs, take-down dogs. Breed, heritage, maternal and paternal lines, in utero experiences and early socialisation up to 7-10 weeks or so means that their capacity to bounce back is going to be pretty low.

Some dogs, like Mabelle, may only ever be a 1 or a 2. She’s a 1 now. I never saw a dog as shut down as she was in a number of supposedly therapeutic events. Traditional methods to reassure dogs and build resilience are slow and hard work. You can put hours and hours in with her only to see the smallest progress.

Still, that’s not to say you shouldn’t try.

It’s not all about what they’re born with, or those first few weeks in a dog’s life. Resilience can be damaged by life. You can’t tell when you’ll run out. I have had three car accidents in my life. The first was fairly serious: I was shunted into a junction by a lorry going 40mph when I was stationary. I bounced back. The second was a fender bender. The third was relatively minor on the scale of things but it left me unwilling to drive my car for months. I still don’t drive in towns if I can absolutely help it. My resilience took a beating that it has not recovered from.

The same is true of dogs, too. I think that’s especially true of working dogs who are surrounded by stressful events. You don’t know what will be the one event that will mark the end of the career of an explosives dog.

It’s not just a lifetime thing, it’s a day-to-day thing too. Resilience runs out and we need rest and recuperation to rebuild. It’s why some days, we run out of spoons and find we need some time to recuperate. I know my resilience globally is pretty good (she says, having experienced lengthy periods of depression!) but my daily resilience can be depleted and then I end up ranting at politicians on Twitter.

The problem is that how humans build resilience is often through talking therapies, through cognitive discussion, through yoga, through mindfulness training, through tai chi and lunch with our friends.

Not so easy to work with a dog on those.

Maslow, good old Maslow, had his wonderful hierarchy of needs

You can even find animal versions of those out there. Some are wonderfully complex and detailed.

But we forget that there’s a big old need in the first layer that will interfere with all the others. Here, it says ‘shelter’, but I would replace that with ‘safety and security’. Safety, for me, is an emotional state. Security is a physical one. I can be secure, lock my doors and buckle up, but still not feel safe.

When we don’t feel safe in acute stress periods, we can’t drink, eat or sleep. When we don’t feel safe in chronic stress periods, our eating, drinking and sleeping get messed up out of whack. Feeling safe, for me, underpins all physiological needs.

That’s why we can’t use food with dogs who are panicking. It’s just not that important to eat a tiny piece of ham when you literally think you are going to die. But it’s also why we need to be careful with using food with dogs in chronic stress… it can form part of a coping mechanism.

Now I love using food. It’s how I turned Shouty Snaggle Toothed Dragon into a fairly polite dog who doesn’t over-react to as many things as she once did. We’re only beginning to understand the effects of food on our emotional wellbeing, investigating things like serotonin diets. Food is my friend. It’s how I work with all the anxious dogs and help them feel safe around me.

It’s also how we know a dog isn’t suffering acute stress. This moment is often the beginning of our relationship with traumatised dogs and it can be really powerful when it’s the dog’s choice. I am a firm believer that dogs who’ve suffered traumatic experiences or who are anxious need regularity and peace to eat, not having to overcome a great big fear of humans just to have something to eat.

But I also know that sometimes it’s an absolutely necessary step because a dog who can’t cope with anything in life is a dog who is utterly, totally and completely miserable. Sometimes, it’s an ethical choice we make to use additional food in ways that we know aren’t particularly comfortable for a dog just so that we can help them make the first steps to a future resilience.

If you aren’t thinking about the ethics of using food in your work with fearful dogs, you should be. There’s no ‘no’ or ‘yes’ in my opinion, but I think we should always be conscious of what we are doing instead of mindlessly proposing gradual desensitisation protocols using additional food that are a tacit way of forcing the dog and removing their choice. Go into it with your eyes open.

Like with Lidy. She didn’t like people and wasn’t resilient around them. I didn’t mindlessly engage in a counter-conditioning programme with her. I knew that the training I was doing, super-mild as it was, was changing her in ways that would not have been her choice. I think we owe it to animals to recognise we compromise their choices and to weigh up the benefits of doing so.

So, safety is a big factor in resilience. And that means providing a safe, regular, routine. It means minimising sensory stress, especially odours and sounds. It means sometimes providing other dogs. Social support is a big factor in resilience and in feeling safe.

We rehome a lot of hounds at Mornac. Many go to specialist associations who understand these dogs very well. The problem for dogs like Leyla (in the photo above) is that they only feel safe in groups. BUT… they then use the group to protect themselves from human caregivers, finding anonymity in the group. That means, again, sometimes being mindful that a dog’s choice of safety will sometimes impede their pathway to more resilient behaviour. It’s not a ‘don’t’ or a ‘do’, more, “just be mindful of…”

The benefits of a canine friend should not be overlooked for less resilient dogs (like the setter here) and having wonderfully chilled out dogs like Habby (the anglo in front) can really help many dogs build resilience.

Play is enormously useful in building resilience – either dog-human or dog-dog. Play encourages you to keep going, to keep trying. Play is also not a possible thing to do when you are in fight-flight mode. I’m hugely interested in how chiens référents (sorry – I don’t have a good translation for that, but I’d say ‘anchor dogs’ or ‘mentor dogs’) can help aid a dog’s recovery and build resilience. Social support is not just about the human caregiver or human companion: dogs learn so much about resilience from other dogs. Lidy, by the way, is a different dog with some male friends.

I call them her bodyguard dogs. Confident, laid-back dogs who model behaviours. I work quite often in kennels with the dogs, and it’s amazing how much watching and learning is happening.

You can see Leyla here with her much more confident boyfriend who is approaching an unfamiliar volunteer. Leyla, bolstered by her familiar humans and a mentor dog can take her time to make up her mind. Curiosity is fertiliser for resilience. Choice is a super-strength booster as well.

That is absolutely crucial. Choice. I’ve become more and more convinced of this as time has passed. The more autonomy an animal has (even the feeling that you have a choice, not necessarily the fact that you do) the more resilient they are. When you realise you can control the universe that’s pretty cool. Of course, dogs also may feel they are controlling the universe by negative emotional actions, the ‘Bite First – Ask Questions Later’ or the flight that Leyla so desperately would have chosen when she first arrived. But controlling the world in positive, mindful, controlled ways is a cornerstone of resilience. People with OCD aren’t resilient. It doesn’t feel good. It’s dysfunctional and yet it leaves them feeling strangely in control. When you have true autonomy, it feels good. It’s a field I’m exploring more and more with dogs I work with.

And of course, none of this would be possible without complementary therapies or pharmaceutical support. For some dogs, the road to resilience is never going to be possible without these. In France, vets rarely prescribe psychological pharmaceuticals without also prescribing a course of behaviour modification. I’ve only known a medical prescription for an older dog that didn’t come with a prescription for behaviour modification. The two work effectively together to rebuild a little resilience. Other therapies can also help. From Ttouch to groundwork, diet and dietary supplements, acupuncture and medicine for health issues, herbal supplements to massage, there are so many things that can help a dog on their journey. Flika had a bad day yesterday. It was 41°C and she was having both arthritis flare-ups and Tenor lady moments. She was uncomfortable, fidgety and stressed. An anxitane pill, an anti-inflammatory, some reggae and a half-hour of massage turned my girl who’d run out of spoons into a girl who was able to rest. No rest and you’ll find resilience disappears. Heston’s soothing is grooming and chewing. 30 minutes of brushing and a good half-hour with a bit of tendon to chew on and it was like he’d done an hour of yoga. We carry stress in our muscles: make sure you give your dogs time to recharge their batteries and discharge their muscular as well as their mental stress.

In all, if you’ve got a 5 or a 6 out of 10 kind of a dog, rather than a bombproof 10 out of 10, make sure you keep those resilience banks topped up with intervals between stressful events (both positive stress like fun walks and negative stress like things they don’t like). Give your dog plenty of proper rest – I know lots of homes where the TV is on right next to the dog bed for 14 hours a day or more! Build in physical contact and care protocols from massage or gentle grooming to Ttouch and acupuncture. Treat underlying aches and pains. Ensure your dog has security and feels safe. Seek out your vet or a behaviourist if necessary. Always factor in social support – both human and canine. Give choices and build your dog’s ability to say both no and yes. Plan for the future and keep that resilience going in careful ways, or you’ll watch it ebb away just as your dog needs it most for vets and medicines and their own life changes.

After all, resilience is like a muscle. You may have been born with the genes of Arnold Schwarzenegger or the ability to bench-press three times your body weight, or you may have biceps like Twiglets, but you can work at it always. Then, when your world turns upside down one Friday evening in the driving rain, it won’t zap your resilience for good.