I read a very interesting chapter in Dog’s Best Friend by John Sorenson and Atsuko Matsuoka that really made me think. It was about a new shelter in Istanbul, and about both its appearance and its geographical position. It really made me think about how shelters look, about the word ‘shelter’ and how we talk about kennels where you can adopt a dog, and about why people find it so hard to adopt.

After all, LOADS of people say that they would adopt… and then… buy a puppy from a breeder.

Why is that?

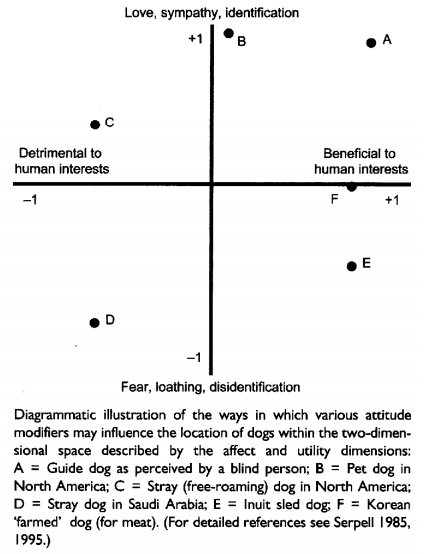

For me, I think there are many factors behind why people say and do different things, and some of it has to do with their perceptions of shelters.

I mean, let’s think about that word for a minute.

“Shelters” in France weren’t always “shelters”. In fact, some still aren’t. The word implies sanctuary, refuge and security. In fact, our shelter is called a “refuge” here in France. The idea of protection is as inherent in it as Societies for the Protection of Animals, or Humane Societies. But despite this word, what people think about kennels from which unowned dogs are rehomed, how those kennels look and what they sometimes do can mean that people are unwilling to buy into the idea that this is what “shelters” do.

In France, that’s not much different than the rest of Europe.

French law says this: stray companion animals are the responsibility of municipal authorities. They have an obligation to either keep the animal themselves for 8 days or pay another body to do so. For us, the municipal authorities club together, pay a subsidy to a syndicate, and the syndicate ask for tenders every two years, then awarding funds to the winning tender.

For the last six years, we’ve won the tender to run the pound services. The pound and the shelter are two different things. The pound is a legal entity designed to house unclaimed animals for a short term. The shelter is a charitable trust designed to protect animals. It’s not unusual to have both the pound and a shelter on site: lots of our local neighbours are the same.

Not all pounds, however, are invested in rehoming or in animal protection. Some run in a financially efficient way, meaning mass killing of surplus animals, just as pounds often have done in the past. Sadly for those of us invested in animal protection, that financial efficiency can mean they place better tenders. That in itself is an issue. But there are plenty of pounds who run on economic models and for whom animal protection is nothing but sentimentalism. That makes it hard for our own shelter to shed the image that pounds kill strays, because it’s hard for the public to know if you are or you aren’t. Even if you aren’t, there’s still suspicion about shelters in countries where there are mixed approaches.

Despite rehoming kennels and traditional pounds being driven by two very separate agendas, many people are understandably confused by these two approaches, which are very contradictory. One is in the business of saving animals’ lives. The other is in the business of managing overpopulation and stray populations. It’s not shades of black and white either. There’s a whole spectrum of grey in between with shelters who must euthanise for space and pounds who rehome, and thousands of variables in between.

All the legal nonsense and mutually exclusive goals aside, what pounds and/or shelters sometimes have to do is so against the ethos of animal protection that some people have a hard time trusting shelters. How can you profess to be saving animals’ lives and also extinguishing them? It leaves many shelters looking hypocritical to outsiders.

Where shelters are charged with population control it can really add to that hypocrisy. The ugly side to the function of pounds and/or shelters that can be so at odds with what we’re supposed to stand for that people don’t trust us not to be dog-catching killers intent on wiping out a species.

It doesn’t help that the laws in most countries permit the legal killing of unclaimed companion animals, thus meaning that even if YOU don’t use euthanasia as a way of managing over-population, other shelters may well do, and the general public have no idea if you or you don’t.

Mostly that picture is the same across Europe and Eurasia. A pound picks up roaming or stray animals (with varying frequency depending on local laws) and (mostly) keeps them for a period of time before killing them or rehoming them. So in countries with highly restricted dogs and high levels of ownership, that pound will be responsive to individual ‘stray’ animals, and in countries with infrequently restricted dogs and low levels of ownership, it’s probably related to times they become a nuisance or a health hazard. In countries where adoption is a culture, fewer dogs will be euthanised, and in countries where supply outstrips demand, more will be.

In very, very few countries or regions do laws forbid the killing of collected animals. The UK and the USA and France are not part of the countries where legislation forbids the euthanasia of unclaimed animals. Just to put that in perspective. A growing number of countries like Italy insist on rehoming, but not all.

So the number one battle shelters face is that in most countries, despite our mantra of animal protection or humane society, we ARE killing dogs and cats. We might not like to. We might have very high live release rates and adoption rates – almost 100% if we can. But we still may kill some dogs and some cats. Even if we do that for medical necessity, we still do it.

It’s at odds with what we call ourselves. A shelter or refuge should be exactly that: protection.

And so, for better or worse, shelters are talked about as if they are prisons, as if they are extermination camps, as if they are death row. And some are.

People talk about concrete and bars when they talk about shelters. And they are right, on the whole. Even if you have pretty parks and glass instead of bars, or even if you have doors and wallpapered walls.

Now that image lingers. Most people don’t feel bad about leaving a dog in kennels for a holiday. We have a really nice kennels near us. The runs are bigger, it’s smaller, it’s cleaner. They have a heated bit. But it’s still the same as a shelter. Quieter and prettier, but still offering the exact same thing.

I mean we have nicer grassed areas and parks too – and nice places to walk.

We even have some bigger park areas where dogs can let off a bit of steam or decompress.

Shelters ARE kennels. Some shelters are nicer than some kennels. Some kennels are an awful lot nicer than some shelters. Some have comfy beds and chairs and grass and heating and others don’t. In reality, it probably matters very little to a dog. But those perceptions matter hugely to people who adopt.

Now don’t get me wrong: our shelter is often a lot better a life for some of our dogs than they have ever known. I don’t want to give the impression that we’re not.

But we still LOOK like a dog prison.

And that is one battle we have to face.

We still face a huge battle, as most shelters do, between protecting animals and sometimes killing them. Even if that’s for medical reasons rather than over-population or behaviour. In fact, we know that, for the cats for example, bringing them to the shelter is a death sentence for some – hence our extensive foster system. The sad fact is that if you don’t have widespread immunity in the local population, and you transplant animals from one area to the other then boom, you’re mixing up sick animals with diseases from various communities with one another. I know that for some of our cats, for instance, simply bringing them from one isolated population has left them vulnerable to diseases from another. The same with all creatures, including people. Even if you may not mean to kill animals, sometimes by transplanting them to a shelter where they are exposed to other animals, that can be a death sentence anyway.

Intensive quarantines are the only way forward – but they can be enormously stressful for animals. We’ve had dogs arrived in French shelters with foreign microchips and no passport who we’ve legally been obliged to quarantine for 180 days! No wonder people consider shelters to be prisons.

I think one of the hardest things a shelter has to do is turn around public opinion of the communities around them, to have an open door policy and to overcome myths that we’re prisons and extermination camps, which make it very hard for people to want to visit. Many people just don’t know what happens behind those walls, and they’re afraid to ask. Rumours spread and they make people less likely to want to adopt. Don’t get me wrong: there are a lot of people who will adopt animals because the shelter kills them otherwise. That doesn’t help with the “big, bad shelter” image though.

Another thing that adds to that is how shelters LOOK. You know, walls and barriers and so on. We’re designed to keep dogs in. We have a 4m high fence and 2m gates. We LOOK like a prison.

That doesn’t make us the most welcoming-looking place in the world. And it also makes it hard for people who don’t come in to imagine what actually happens behind the walls. Those barriers to reduce noise and keep dogs in also keep people from seeing the good stuff going on. For all they know, we’re an extermination camp for dogs.

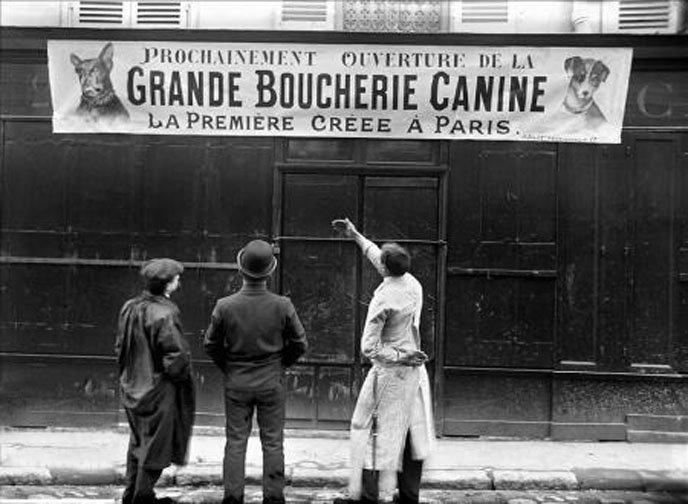

It doesn’t help that this is once what MOST pounds were. I mean, 19th Century New York, stray dogs were rounded up, put into cages and drowned in the river. No wonder rumours build up about what we’re doing behind those walls. For many “shelters”, this is what we still are.

So one of the tough things shelters have to do to battle public perceptions is get out there and open doors. If we truly want to be seen as protecting the legal and moral rights of companion animals, we bloody well better do that. If we’re in a country where the law allows us to kill surplus companion animals and we do differently, we bloody well better say so. And if we don’t, we need to be honest about that too. If we aren’t, or if we’re just quietly getting on with the daily business of protecting animals, we run the risk of being seen as inauthentic by our local communities. Only when they trust us will they adopt from us because they trust in us, share our values and believe in what we are doing.

This is hard though, walls and gates and prison-style kennels apart.

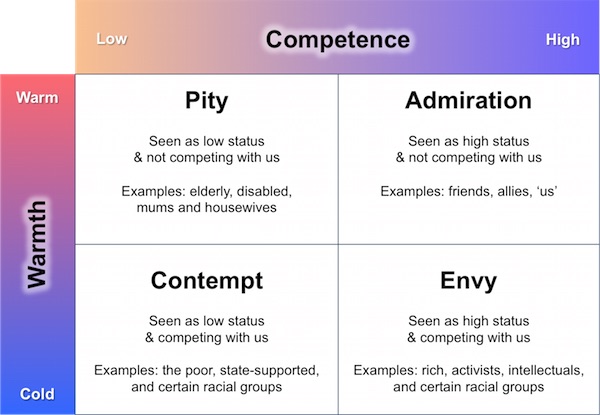

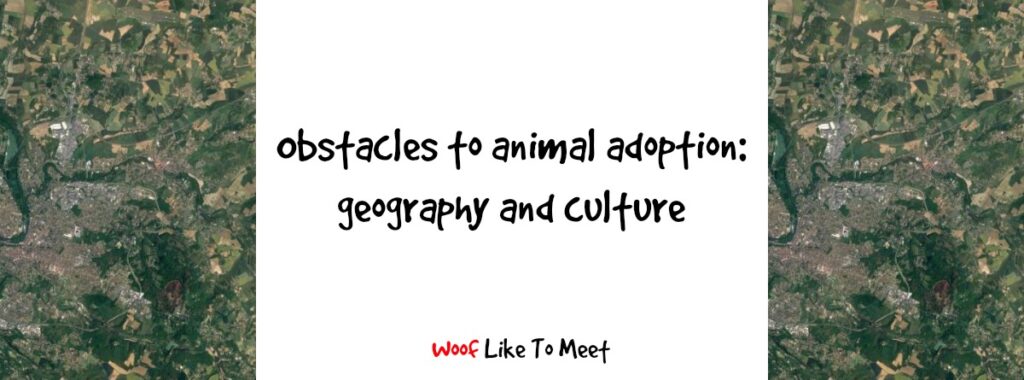

Another factor that Sorenson and Matsuoka’s book made clear was the geographical location of shelters and how that leaves many as physical outsiders, a physical “othering” no different than happens with some ghettoised human groups. Just as segregation does with human populations, this geographical distance creates more than just a physical barrier.

Take a look:

One local shelter is down at the end of an unpaved dirt track, trapped between the river, a high-speed train line and a motorway, surrounded by industrial estates. It’s fairly well signposted, but it is clearly an after-thought. Would you stop by for an Open Day or a public event? “Come on Karen. Let’s spend the afternoon by the High Speed train tracks.”

Thought not.

Isn’t is interesting, though, how the way shelter animals are valued in society mimic the places they are kept?

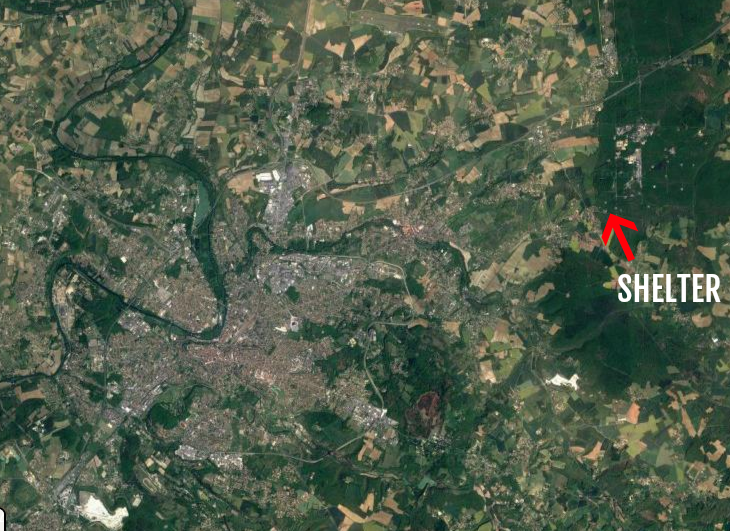

This is the same shelter so you can see it in relation to the rest of the city:

I mean you might as well say the animals there are the untouchables, the Dalit, the unclean. They are literally next to the water purification station. The sewage treatment plant. That’s a metaphor and a half, isn’t it? The place where our shit gets cleaned up.

One more, so you can see I’m not making this stuff up… literally in the middle of some woods. The grey strip on the bottom right is a runway for the local airport. I mean you don’t get more forgotten about.

I mean you can get some sense of how shelters are geographically outcast from this aerial map of the same shelter:

And us?

Sure, beautiful forested area with lots of space to walk our dogs… 1km from a waste sorting site, a dog food factory and various other stinky and unsavoury industries.

A forest owned by the National Forestry Commission who run hunts with dogs right on our doorstep every Friday from September to March. The same commission who we lease the land from, who pave our roads, who provide our fencing, and to whom we need to be bloody polite about the abuse of animal rights literally on our doorstep most weeks in case they decide we’re a nuisance and kick us out.

Some Fridays, it doesn’t half feel like ‘Know Your Place, You Bleeding Hearts’… I won’t tell you how many hunt dogs we get in. I think my point is clear enough.

You can also get a sense of how far out of the city we are:

Believe me, we are not well signposted. I’m forever giving out GPS coordinates and asking would-be adopters to use sat-nav.

Does anything say “untouchable” like the geographical position of a shelter?

Now don’t get me wrong: maybe nothing was meant by all of this. It’s sensible to have noisy, smelly places out of suburban or residential areas. Not In My Back Yard, right? Also it’s quieter for the animals too. It’s not all bad.

But that physical isolation causes two problems. The first is that it adds to the mystery surrounding what happens in shelters. Not easy for people to know what is going on when you have low volume traffic. I mean, it took me no time at all to see where the new McDonald’s was going in my town. I went there one time to meet a friend for coffee and I was seen by five people I know who were driving past. Everybody sees what’s going down at the McDo car park. But tough to do that with a shelter.

The second problem is it literally distances adopters from the animals. In a way, that’s fine, because if you want a dog or a cat, you’ll make the effort. But it makes it tough to get volunteers or even staff. Irregular bus services or public transport make it a nightmare to make good use of young people who might be the first step in changing the minds of a community.

That’s worse still for us here in France, as a large number of big towns and cities with nice suburban areas and plenty of great places dogs and cats could live… they don’t even have proper shelters. I mean we’re one of the largest shelters in France and … we serve an area with a below-average population density and a town that is the 171st largest in France. Bordeaux, by contrast, a much, much bigger city, has no shelter. I need not explain to you what happens to stray animals there.

But what that means is that all the lovely people of Bordeaux – and wealthy urban liberals tend to make really good adopters who buy into the ethos of shelters – would have to drive 2 hours or so to find themselves a shelter dog or cat. And if that shelter needs a homecheck? Wow do the logistics get tricky.

Where countries do have networks or franchises of shelters, which France does a little, that can ease things by moving dogs to places they’re more likely to be adopted. At the same time, it’s a crying shame a big old town like Bordeaux is just sitting there without any way to help out.

What does that mean for shelters?

The first thing is to consider your geographical location and your surroundings. Are town dumps and sewage plants linking your shelter with emotional responses of disgust and dirt? How far are you from the kind of residential areas that would suit your animals?

Once you work out that depressing picture, you can at least begin to combat it.

Now I’m not suggesting hauling arse into the city with a busload of shelter animals, though yes, some shelters do this, but it’s worthwhile thinking how you can market your dogs better and get them seen in the places they should be seen.

As a sensible animal lover who also knows the bite risk of taking live animals from one stressful environment to another, I’m more a fan of publicity stands with one or two bombproof demo dogs. I mean you can’t take all your animals up to the big city (we have around 400…) so chances are, your ‘customers’ will need to drive out anyway unless they want that exact dog or cat you’ve taken into town. Plus, if you’re good at online marketing and you have reached a good level of foot traffic as we have, our easily adoptable dogs are gone in hours or days, which leaves us in the unenviable position of trying to take our more complicated dogs into town. Not for me.

Social media definitely helps bridge the gap. Photos, videos, stories and posts all help people know what happens in your shelter and helps them arrive with animals in mind. You wouldn’t think there are shelters who aren’t on board with that yet, but I KNOW at least five local shelters where they have had to have some big arguments about whether to use social media at all or not.

For us in France, we’re behind the times.

We don’t have rich charities who can pay for social media teams like the UK does, or like some shelters in the US. It is very much a grassroots kind of thing. I mean “social media” for one of France’s largest shelters is basically a team of five volunteers. But it works.

That said, you have to go through some pretty uncomfortable periods where frustrated individuals berate you on Facebook at midnight because you wouldn’t let them adopt a St Bernard as they lived in a 10th floor apartment and work 8-6, or some heartbroken couple who share stories of their kitten who died of FIP shortly after adoption, unwittingly giving everyone the idea that all your animals are sick and diseased.

And if you kill dogs and cats for space… that can make some shelters very reticent to share their animals only to then have to explain “we killed this one for space” and face uproar in a community that don’t understand. People follow posts. They want to know what happened to Mabrouk or Mabelle. Heaven help you if you don’t have a good answer. Of course, we also know those shelters who work with the !!!!!THIS DOG WILL BE EUTHANISED TOMORROW AT 7AM IF NOBODY ADOPTS THEM!!!! and seem to be torn either between having no shame or being completely desperate. Or both.

What is important though is recognising the geographical problems you face as well as dealing with misconceptions about what you do.

It’s important to build up an authentic relationship both in real life and on social media with people who share your values and who will adopt from you time after time. Nothing is more satisfying than seeing people coming back again and again, becoming involved in a community. With so many shelters being geographically outcast, it’s vital to build a community who work by word of mouth. I mean, in my tiny hamlet, the number of dogs and cats from our shelter has gone from 0 to 9. I know I have two of those animals, but even so… as a friend said a few weeks ago, “you’d have to be bloody hard-hearted in our community NOT to have a shelter dog”.

That brings me to a final point.

You may do everything you can to open up your shelter to the world and people will still find it hard to cross the threshold.

Whether people believe you’re dog catchers out to kill all the dogs in the world, or whether they’re just not ready to face a wall of dogs who remind us of our failings as a species, some people are going to find it hard to cross your threshold even if they say they would adopt.

Shelters can make this easier by bringing dogs out of the shelter, using areas that have a more home-like feel or even using foster systems.

Foster systems, for me, are the future. We’re not there yet at our shelter because so much of our client base is – believe it or not – foot traffic. It’s changing, and we’re already changing for the cats, where most of our kittens are off-site. We’re happy to lose those “customers” who want to “buy” a kitten in 10 minutes. But we’re not there yet, and most of our dogs in foster are there for age or medical reasons. We’re yet to start using fosters for behavioural reasons or for other reasons. People still turn up at the shelter and expect to “buy” a dog in 30 minutes as if they are buying a pair of shoes. That’s one behaviour our cattery staff and volunteers have been really good at fighting. But we’re not there yet with the dogs.

It’s not just about getting out into the community. The truth is though that fosters – even short term ones – can be really good for dogs who need a stress break from the shelter. Gunter et al. (2019) found that temporary foster systems for short stays were as effective as you’d expect at reducing stress levels short term.

That said, not only are foster systems good for dogs, they can get the dogs into parts of the community shelters don’t normally touch. What wouldn’t I do to get shelter dogs in a foster network in Bordeaux? I daren’t bear to tell you. When foster dogs have lower cortisol levels and are more likely to cope with outings, that makes it easier to take them to public events. Mohan-Gibbons et al. (2014) found that foster programmes were a great way to get dogs to the places where they might be adopted and to break down the geographical barriers to adoption.

For me, shelters have a long way to go to move opinion from animal control. That’s made much harder because of the geographical location of many shelters. Foster programmes, social media and other outreach work can help shelters encourage more people to adopt. Opening our doors and engaging with the community may be the first way to achieve that.

Next week, in the final post in this series, I’ll be bringing the last posts all together to help shelters make the most impact in adopting out animals successfully.

Gunter, L. M., Feuerbacher, E. N., Gilchrist, R. ., Wynne, C. D. L. 2019. Evaluating the effects of a temporary fostering program on shelter dog welfare. PeerJ 7:e6620

Mohan-Gibbons, H., Weiss, E., Garrison, L. and Allison, M. 2014. Evaluation of a Novel Dog Adoption Program in Two US Communities. PLoS One 9(3): e91959.