What makes us pick a dog? Why this dog? What is it that makes us just click? Why do we have a preference for spaniels or poms or beagles or German Shepherds?

Once, long ago, a fledgling idea crossed my mind that led me to pick a name for the stuff I was doing. Woof Like To Meet. A matching service for people looking for a shelter dog.

I like to think that a part of me knew then that some dogs just appeal to us more than others. In reality, I’m just explaining a choice I made 6 years ago because it was cute.

But it became a bit of a sport. What dog would people go for? Could you look at a person and know what kind of dog they’d pick? Anyone involved in shelter adoptions and relinquishments will know what I’m talking about.

It comes down to stereotypes and prejudices more than anything. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had conversations with Identikit guys who’ve had their pit-bull seized. You know. I wish one day they’d NOT conform to that type. I can spot who’s likely to pick out a poodle at fifty paces.

I remember watching Ricky Gervais handing out jobs for dogs and laughing at the stereotype about miniature poodles being carried around by elderly homosexuals. Except in France, that’s not true at all. Your average poodle owner would be an wealthy, elderly widow who lives in town and whose children had bought her a poodle for company after the death of their father. We get one or two surrenders of apricot poodles from time to time and they’re always like that. Mainly because their owners go into nursing homes or die themselves and the children don’t want the dog. Of course we don’t get apricot poodles from middle-aged gentlemen who might not die quite so quickly. I really need better demographics than my own narrow observations. There may well be a large number of poodles living out lives doing canicross and dock-diving and search and rescue who don’t end up in rescue. Better data is always needed before you start judging dogs and their owners.

Having just finished my dissertation for my Advanced Diploma in Canine Behaviour from the International School of Canine Behaviour and Psychology (sorry for the humblebrag!) I decided to focus my analysis on why people pick certain dogs. Be that types, breeds, looks or labels. I’ll be publishing this series of articles in relation to that, and the next five posts or so will be exploring my findings. But what makes us pair up elderly homosexuals or les mamies veuves with poodles? What makes that happen?

What do dogs say about us? Do we pick them to say stuff about us? Do people really pick dogs who look like them? Do we pick out dogs that share our temperament? Are they just a way of saying to people, “Hey look! I own a Turkish Piebald Leaping Dog. Look how unique I am!”

That’s what I wanted to know.

And, more specifically, what does a former stray who’s spent time in a shelter, say about us? Are they really nothing more of declaring what saintly people we are?

In order to find out, I read a lot of studies and I carried out some interviews. Some of the stuff I read was so interesting I needed to share it with you. I hope that it’ll be useful for shelters too, by the time I wend my way around to explaining that.

Sociologists and anthropologists who’ve focused in on human-animal relations say animals have socially constructed meaning.

What I think that means is that the label we give them is a short-hand way of saying how we view them and how we treat them.

Writers like Arluke and Sanders, Hal Herzog, Jessica Pierce, Peter Singer, Nik Taylor, Samantha Hurn and Marge DeMello have explored those socially-constructed labels for animals: lab animal, livestock, food, clothing, entertainment, weapon, pest, companion animal…. how we label animals then affects the moral and legal rights they have. It affects how we view them and how we think about them, as well as how we use them and even how we kill them.

Those writers look mostly at all animals and big categories. I just wanted to think about dogs. I liked thinking about other animals, sure, and it was interesting and complex. Like why we eat cows and hate snakes and love dogs, but if you eat snakes, hate dogs and love cows, you’re weird – or worse still if you eat dogs, hate cows and love snakes.

It just struck me that we use dogs in so very many, many ways. More than most other animals.

Maybe that’s because they are hugely successful as a land mammal species. 1 billion dogs, estimated, potter about this planet of ours. The number of pedigree dogs is surprisingly small and keeping dogs of named breed is inextricably tied up with development and wealth.

But how we think about and use dogs covers so many categories. I wished those authors would write in as much detail just about dogs.

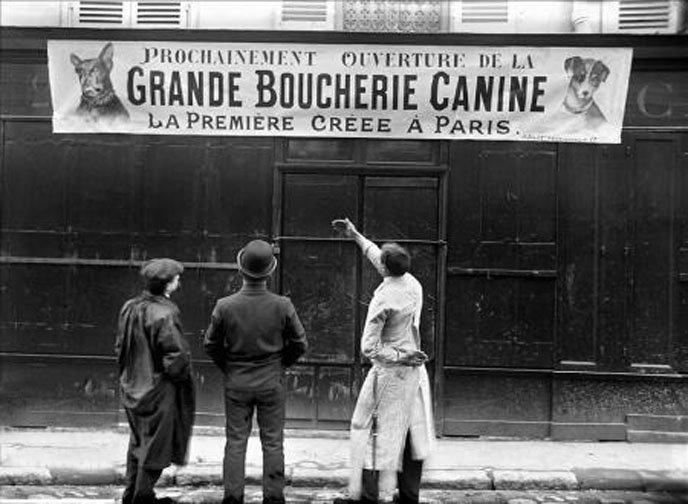

Dogs are food in some countries. In fact it wasn’t so long ago that we in the West wouldn’t have had to look quite as far to find dogs bred for the plate. It tends to cause outrage and disgust in quite a few societies who really don’t have to look too far into the past to find the same.

Like this Belle Epoque butcher in Paris, for instance.

And dogs, as we know, are used in laboratories. We at the Refuge de l’Angoumois work with Association GRAAL to rehome beagles who’ve been used in labs. I guess, after the great apes and monkeys, our moral outrage about dogs in labs is next on the list.

We also use dogs as breeding livestock on farms, just as we might breed pigs and cows, sometimes to consume in some cultures, and sometimes as a commodity in others. Puppy mills or usines à chiot make money off the back of this commodity just like we might off any other livestock animal.

Dogs are clothing: I don’t have to tell you where some of the fur trimmings come from on festive hats or gloves. It’s not just for Cruella de Ville.

Then we start to specialise. Dogs are entertainment, be that in dog fighting rings and racetracks or on the screen.

Dogs are weapons, whether legally held or illegally. From disarming terrorists or guarding a building on the one hand to their use in drugs rings to protect stashes, cash and dealers.

Dogs are tools to help us turn spits, to drag sleds, to hunt other species, to keep down pests, to protect our sheep. Some are even named after this function. Retriever. Pointer. Shepherd. Terrier.

Dogs are prosthetics, acting as eyes, ears and hands. Some of them do that officially, and others just freelance. They’re a literal extension of ourselves.

Dogs are a commodity, a brand we choose like washing powder or soup. They’re even used to market other commodities like cars, toilet paper or paint.

Dogs are metaphors that help us explain that someone is ugly or sexually promiscuous, or in the dog house. They are artistic and literary symbols that help us understand class angst (like Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights) or social standing.

Dogs are companion animals, even family members. They can be closer to us than many of our friends or family.

And the category I’m most interested in is ‘dog as pest or nuisance’. Because for a long time, that’s what ownerless stray dogs were. Out of their ‘normal’ geographical space and out of their ‘normal’ relationship with humans, dogs considered as pests are the strays shelters are charged with rehoming. Some, of course, are strays. That implies ownership. I don’t see a pigeon and say “man, the problem round here is all the stray pigeons”. It means you have a place you’re supposed to be and it also means your movement is restricted because of some strange thing called culture. Others are ‘village’ dogs, implying they’re communal property but nobody really takes ownership of them. Some are street dogs, as if they’ve never had a place within the family. We sometimes use the word feral, but feral dogs don’t really exist. Feral means a return to pre-domesticated status, and dogs, as far as we know, don’t have the ability to turn back into the long-dead ancestral wolf they once were. We use feral differently of course. But even then, there are few dogs who could live completely outside human spheres, untouched by human behaviour.

Our track record with other species ‘out of place’ isn’t good. Nuisance animals are often killed in the most brutal and inhumane of ways. Where lab dogs and companion dogs have very strict laws about who can kill them and how, dogs who are pests are often killed in the least efficient and most violent ways.

Like the turn-of-the-century dogs who made it onto the table, we Western countries don’t have to look too far into our own pasts to find the ugly canine skeletons in our closets.

Partly, this is tied up with disease management, particularly of rabies. There is a correlation between evolution of welfare laws and decreases in rabies. But New York used to round up strays, pack them into cages and drown them in the river not so very long ago. ‘Shelters’ are a modern notion: in the past (and very often in the present) they were simply a holding pen for dogs awaiting death. In many places, seeing a pack of stray dogs inspires the same feeling of disgust and fear as seeing rats. Strychnine, electrocution, drowning, gassing and shooting are commonly-used methods of killing such dogs, just as they are with any number of other species considered pests (even humans, much to our global shame).

Two dogs show me how little stray or ownerless dogs were valued not so long ago. One is Laika, the first dog in space. A Russian stray, being sent on a death mission into outer space has somehow glossed over the fact that Laika probably wouldn’t have been used in such a way if she was Khrushchev’s pedigree pup. The second dog is actually a group of dogs. In the sixties and seventies, psychologist Martin Seligman and his team used stray mutts to experiment on to teach us about learned helplessness. That involved electrocuting dogs until their muscles gave out in some cases. Though these ‘harms’ to ownerless dogs are far from rare, and in many ways are arguably less unethical than slow starvation or any other way of reducing stray dog populations, for me, they are strong symbols of just how recently ownerless dogs were outside what we in the west might classify as acceptable.

Why all this interesting yet seemingly theoretical musing is of interest to me is because it affects how we see shelter dogs, and that affects their adoptability. A pedigree dog (or at least one that conforms to type) will often, more easily, walk out of the shelter in days if it’s a breed that society approves of. Society still sees dogs of no known ancestry as ‘mutts’, ‘mongrels’, words we use to suggest impure, imperfect. Words that express our disgust in ways that we don’t feel about ‘mutt’ cats or hamsters. Even writers who take issue with being called the owner of a dog or with the word pet are happy to use the term “pure-bred”. In fact, I’m so conscious of this that instead of referring to my boy Heston as a mutt (12.5% GSD, 12.5% cocker spaniel, 12.5% labrador, 12.5% ‘other’, 50% groenendael) I call him a groenendael cross – largely because he kind of looks a bit like that and I can get away with it.

To be fair, France (the country our shelter is based in) has a high proportion of “type” dogs who look like an identifiable breed. Largely that’s based on a long working history with dogs and then quite a lot of breed-fancying from the 1870s onwards, briefly bottle-necking in WWI before continuing freely since then. We don’t have many dogs whose heritage isn’t immediately visible.

Flika looks like an elderly malinois because, largely (87.5%) that’s what she is. Apart from the 12.5% of her that says Great Grandad was a German Shepherd. Oops.

Few dogs look like mixed up muttleys in our shelter; they look like pointers, setters, terriers, shepherds, labradors, American staffordshires, breton spaniels, dogue d’argentin and so on.

But that tells you a lot about this pursuit of ‘purebred’ – those words that euphemistically gloss over the genetic manipulation, inbreeding and reproductive control that is fashionable.

When we in the west want a dog, we have 1 billion dogs to choose from. The ones we choose speak volumes about us, about our culture and about our social backgrounds. We eliminate a few million pedigree dogs from our choice list if we choose a former stray of unknown heritage. We eliminate a good few more if we choose to adopt in our own country rather than abroad – by my estimates, France has some 112,000 stray dogs available every year, most of whom are more ‘type’ than ‘breed’.

Dogs in shelters (and shelters themselves) still suffer from the stigma and stereotyping of how we label them. For many, a shelter animal or even one from a breed-specific rescue association is unthinkable. We’d prefer to adopt a puppy in the hopes that we can mould it effectively to our lives rather than choose an adult dog of no known heritage. The fact that 112,000 other people perhaps thought the same about the dog who ended up in the shelter escapes us. We may have the best intentions – like the people who ring me up and ask if we have any bichon frise, preferably female, of less than 6 months of age – because we might reject that awfully economic way of acquiring a family member by going to a breeder.

Because of the way we categorise dogs, we have an awful long way to go to overcome shelter stereotypes. British shelters are not filled with greyhounds, staffies and Jack Russells. French shelters aren’t all filled with hounds. Romanian dogs aren’t all ‘streeties’ without valid passports. Most European shelters do try to rehome rather than euthanise. Dogs in shelters don’t have behavioural problems. But shedding that ‘disgust’ and ‘contempt’ lip curl and sneer about shelter dogs (much, much more than shelter cats who don’t suffer from the same stereotypical labelling) is a vital role for shelters to undertake. We may have stopped serving dogs for dinner or drowning strays in rivers (on the whole) but the stigma attached to having once been classified as a pest still sticks to many of our dogs.

Shelter dogs have a tough role too because many of them will have been seen as something else before. They may have lived completely beyond human reach, responsible for their own lives and reproduction. That is rare in France. They may have been treasured family pets. They may have been in a lab. They may have been rescued from the dog meat trade. They may have been a weapon or entertainment or ex-puppy-mill breeding stock. Shelter dogs often carry more than one label, more than one understanding of how humans treat them. Sometimes, we leave the shelter label on there too. How many of us know a ‘rescue ex-racing greyhound’ or a ‘rescued puppy mill dog’? They often carry those labels through life forever.

As I come to the end of this piece about how our social categories of dogs affect them, I thought I would mention their use as a symbol. That is where I’m going on the next article… an exploration of how certain breeds or types of dog have been used as a symbol in many ways. Despite many people’s thoughts that shelter dogs may be a way of signalling how holy, how virtuous or how ethical we are, none of my research found that. What I did find was that although people may arrive at shelters asking for young female bichons (and heaven knows we have plenty of calls if we have any) people view shelter dogs (and definitely those shelter dogs of undefined ancestry) differently than we view pedigree dogs.

In the next post, I’ll be taking you through why I think agility classes are filled with women of a certain age, why a guy asked if I could put ‘cross’ after ‘poodle’ on a pedigree dog’s registration details and why the pit bull has become the avatar of choice for certain disenfranchised young urban men. It all brings me back to what one of my study’s participants said: “read the dog, read the owner.”

If you’re looking for some interesting reading, try:

Horowitz, A. (2019) Our dogs, ourselves.

Herzog, H. (2010) Some we love, some we hate, some we eat.

McHugh, S. (2004) Dog.

Pierce, J. (2017) Run, Spot, Run.

Sorenson, J. and Matsuoka, A. (2019). Dog’s best friend? Rethinking canid-human relations.