In the last two posts, I’ve been looking at how we view dogs as a social construct, and then how we view dogs who belong to a small group with a name of its own, known as a breed. Today I’m looking at how we view strays, rescues and shelter dogs, before, during and after their arrival at the shelter.

Most of the world’s dogs live unrestrained lives. With around 200m dogs in the handful of post-industrial, developed countries and another 800m or so in the rest of the world, it’s only in recent times that restraint and ownership have really come into their own. Some dogs living in some cities now have the misfortune to only be allowed in very, very specific places. If your landlord agrees, and the other tenants agree, and you keep your dog tethered on the street, and you have a dog park, your dog might have a tiny modicum of what we might consider freedom. Their rights to eat what they want, go where they want and reproduce with whichever dog takes their fancy are so very narrow that we now have to consider enrichment activities as if they are zoo or lab animals.

I make no judgement on that, by the way. It’s just a description of how some dogs live in the modern world.

Some countries don’t face problems with unrestrained populations. I am, by the way, going to leave ‘unowned’ populations until later because that’s different again. Unrestrained doesn’t mean unowned. The cocker up the road is a perfect example. You can spend your days at liberty without meaning you don’t have a name on your ID documents. He wanders about a quiet village to his heart’s content. Sure, he annoys all the other restrained dogs, but c’est la vie. Lots of things annoy restrained dogs.

Unrestrained dogs were fairly regular in my childhood, despite leads being more and more common. In British suburbia we did have dogs who took themselves off for a walk in the 70s. But most of the dogs on our street lived restrained lives, from the westie at number 1, the pair of chows who lived at number 17, the labrador next door, the collie at the end of the cul-de-sac and our own cocker spaniel. You can see one reason why on this photo…. cars. The invention of the automobile changed a lot for dogs.

In the US, in Australia, in Japan, in France, in the UK, and in many other post-industrial societies, the gradual loss of freedom for our dogs has been an on-going process these past few decades. The wealthier the country (or even region) and the more urban it is, the less likely it is that unrestrained dogs will be tolerated.

We still get ‘stray’ dogs – owned dogs (whether identified or not) who are temporarily unrestrained. Whether they’ve escaped or got out or been let out… there have been times my own dogs have been stray. Temporarily unrestrained. But they don’t live in complete freedom.

We don’t have populations of dogs who live unrestrained, ownerless lives in north-western European countries. It’s why I always laugh about that stray dog myth going around about the Netherlands, that they have abolished their ‘stray dog’ population. No they haven’t. Any such country, where dogs live and are restrained, might accidentally face a sudden break for freedom. What they mean is that the Netherlands, like France, the UK, Germany and a large number of largely northern, largely western, European countries, don’t have dogs who live permanently unrestrained or ownerless lives. You know, Call of the Wild stuff. The Netherlands are certainly not the only country not to have dogs who live permanently unrestrained lives.

In a number of those countries, reducing unrestrained and unowned populations has also been linked to the (practical) eradication of rabies in dogs, like in France for instance. But remember too that a number of these countries who like to brag about their lack of dog problems and bemoan those in southern or eastern Europe (and the rest of the world) are small populations over vast terrains that are largely unsuitable for dogs to live in because there’s a) nothing to eat and b) nobody to mate with. Scandinavia just hasn’t faced the same issues Germany or France have.

In post-industrial countries with large, dense populations like Japan, France, Germany and the UK, we got there by extensive culling of dog populations, a move to bought dogs rather than found ones, and by the commodification of dogs in general. By turning them into property, giving them identification details, having licences and legal obligations, we’ve removed the majority of what were once unrestrained dogs or unowned dogs. We may get strays, but we do not have large populations of permanently unrestrained or unowned dogs. That didn’t come into being in glamorous ways where people suddenly started thinking differently about dogs’ freedom and ownership: it came by mass culling as well as legal and cultural change about restriction, sterilisation and ownership. Ironically, the cultures where we find it abhorrent that others kill stray dogs are ones where we had to cull a large number of dogs just to achieve that coveted status of being a ‘no kill’ country. And worse still, a lot of those cultures where we believe mass killings of dogs is unethical are ones who still practise it whilst at the same time demonising other nations that do. Tricky, this morality and ethics business.

How we currently deal with those who are temporarily unowned or unrestrained dogs in Europe depends on many things. In some countries like Italy, some dogs may languish in shelters as it is illegal to euthanise. In others, such as pre-2014 Denmark when legislation changed, if you wanted to shoot such a dog, you could. In countries like the UK and France, the futures of these dogs (and cats by the way) are shrouded in secrecy in many cases: moral outrage means that if shelters euthanise, they are subject to intense public scorn, and if they don’t, they may end up with dogs in kennels for a long time. In other countries like Spain, it varies region to region. In some countries, dogs and cats are killed on capture. In others, there is a legal delay of between 3-90 days before municipal authorities can kill unclaimed dogs and cats. What’s important to remember – the “gold standard” of 100% identified dogs with 100% accurate details, 100% restrained lives and as close to 100% reclaiming/rehoming if they are temporarily unowned – is a work in progress for most countries. That is easy in a country of one person. It is easy in a country with one dog. It is not so easy in a country of 80 million people and 8 million dogs.

Outside our very blinkered Northern/Western Europe paradigm, the picture changes. Dogs do live unrestrained lives.

“Unowned” dogs might not have one named owner, but they still might belong. Dogs like this might even have a number of humans that they consider sources of something useful – whether that’s a place to sleep, someone who feeds them or gives them water. The dogs, whether they are urban or rural, might be known as village dogs, pariah dogs, street dogs or so on. They, collectively, depend on us, collectively.

In some cultures, that’s accepted and encouraged. Nobody owns them and most people care for them in some way or another.

In others, dogs like this are seen as a nuisance, especially to us wealthy post-industrial tourists. Sometimes, dogs are seen as a nuisance due to over-population or failure of trap-neuter-release schemes. Other times, public policy changes as the country develops, and what had been a fairly benign relationship between communities and their dogs then becomes antagonistic as society tries to clean itself up to emulate Western European standards. Witness the mass round-up and slaughter of dogs in some cities before global events like the Olympics, for example. As societies move from a benign or tolerant approach to dogs, or even one where large populations are sporadically culled, into a world of new media where both unowned and/or unrestrained dogs are not tolerated by people in the west who impose their values on other countries both for having such dogs and for trying to deal with the problem, we then get a number of interventions.

Some of these interventions have been successful, such as trap-neuter-release schemes in Bali and other SE Asian countries. Others are less successful (and I’ll add this in very big capital letters is very much my OWN opinion and you’re very welcome to challenge me on it), by transplanting dogs who have lived permanently unrestrained and unowned lives into countries where they are then subject to fairly intense restraint. That’s not to say that dogs who’ve lived family lives in one geographical area can’t make great dogs in another, but in my opinion (let me stress that) we need to think carefully about the kind of lives we are offering to dogs who have come from living on the streets and whether it is fair to ask them to adapt. We Cultural Imperialists like to do such things – witness all the 19th and 20th century attempts to ‘domesticate’ indigenous peoples by displacing them into “civilised” places – and I think it’s worth an ethical conversation with ourselves about what consequences there are. As long as we’re having that conversation and we know it’s truly for the best for that animal as an individual, then I think we can live with that.

If you disagree with me, as well you might, ask yourself how we manage cats and how we think about cats. Cats are (and this is not my opinion) as worthy as dogs, but we humans feel peculiar about dogs in ways that would take 10 books and several encyclopedias to explain. I include myself in that, of course. But we don’t call cats “rescue” cats, we don’t fly thousands of miles to pick them up, and when I travelled through Morocco’s ports with a number of kitty friends, I did not think I should send them back to the UK as a solution. Thinking of things that way can sometimes shine a light on our own Western behaviour of transplanting populations of animals without consideration of their welfare. Of course, those decisions are easy to make when there are benevolent trap-neuter-release schemes and education programmes designed to help dogs stay in situ and help the public know how to have a relationship with these dogs, but it is not an easy decision when someone is sharing photos on Facebook of dogs in a pound who will be killed the next week if no home can be found. Ethics are great in theory, aren’t they?

A lot of it is about how we feel about unowned and unrestrained animals, though, as a culture.

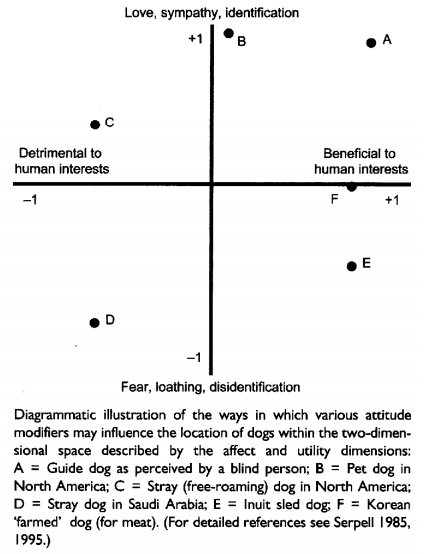

James Serpell (2004) plotted animals (and dogs) on a graph of emotion vs usefulness.

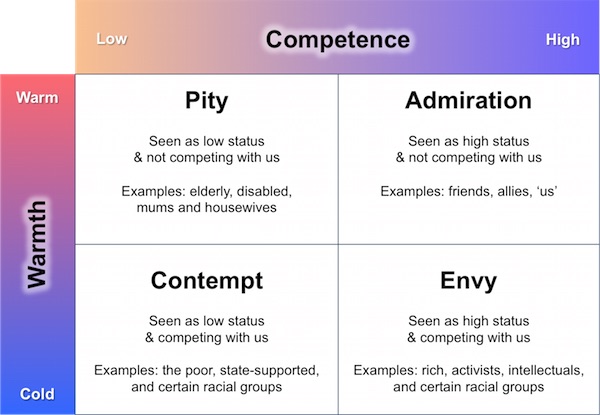

I think this is a useful way of looking at dogs. At the same time, social psychologists were busy doing a similar thing showing how people thought about other people:

I don’t see these as different in many ways. We have dogs we admire, like service dogs and support dogs. They are useful (competent) and we like them, having warm feelings towards them. The effect that dogs have, by the way, transfers to humans and makes others more likely to talk to us if we’re in a wheelchair, get us a phone number or get them to be helpful. The role of certain types of dog as ice-breakers is pretty well established.

We have dogs who we don’t like so much but who are useful, like security dogs or guard dogs for example. If they seem biddable and friendly then we might feel more warmly about them. But otherwise, we tolerate them and are a bit scared of them. Unlike humans, they’re not competing with us, but they might pose a threat if we’re on the sharp end of their teeth if we’re taking drugs through airports or messing with explosives. In France, many French feel “cold” about working dogs like hunt dogs, even though the dogs are useful. It’s one of the problems we struggle with at adoption, as British, Dutch, Belgian, Swiss, Austrian and German adopters love our hounds, pointers, setters and spaniels, but convincing a French person (of a certain age) that they are family pets is another thing entirely.

For stray dogs, whether temporarily unrestrained and unowned, or permanently, we may feel contempt and loathing, or pity. It’s these feelings shelters may have to deal with, that people don’t feel the same about such dogs as they do about guide dogs. If they look sweet and we find them appealing, we’ll feel pity and if they look ‘cold’, we’ll find ourselves having a reaction on a purely emotional level to them that is one of disgust or scorn.

You’ll see how this works. This is Ania. 13 years old and found as a stray. Do you have positive feelings of pity? A pang of ‘Aww?’ A sense of outrage on her behalf that this has befallen her? Do you feel sorry for her and feel like you want to intervene in her life? She’s not ‘useful’ – but she definitely makes us feel warm towards her.

If you don’t, I think you need to visit a cardiologist, pronto, and check out if you’ve got a cold lump of granite instead of beating living tissue in there, you stone cold beast.

Then poor Oural here who looks scared… most people don’t have the same response to an ‘awww’ for him. If I add that he barks, that he growls (he doesn’t but if you came to the shelter, we have dogs who do) and that he’s suspicious of people, immediately all the warmth starts to drop… some people and cultures feel less warm about boy dogs (those puppy dog’s tails) and about dogs with pointy ears (seriously) and we start moving from pity to contempt.

Now of course we pick up on this when we ‘market’ shelter dogs. My bloody heart breaks when I see old dogs in shelters. But I know disgust vs pity is a fine line and based on personal views. Not everyone thinks an old dog is something lovely and it might well make you feel scorn or disgust rather than pity. But I know enough people adopt dogs they feel sorry for, and that’s why Ania here will find a home quicker than Eden

Ania has that air of dejection that Eden lacks. Despite the fact this boy lived all his life chained up in a garage filled with rubbish, despite his similar age to Ania, despite even those floppy ears, we just don’t feel the same, especially when we visit him and our feelings of ‘awww’ fade as we realise he has a few ‘nuisance’ behaviours in kennels. Result: Ania will have a stay of days, and Eden has had a stay of years.

Our feelings about dogs in shelters are impaired also because of perceptions they aren’t good dogs. We might blame the dog, we might blame the former owner, we might blame the shelter experience itself. We might not even like that we feel this way, but we can’t ignore it. We might blame culture and our rational thoughts tell us pit bulls are not responsible for how they’ve been created whilst at the same time, our emotional systems are telling us that these dogs don’t merit the same response as a cocker spaniel. That’s borne out thousands of times on social media shares. Small, young female cocker spaniel? She’ll be shared thousands of times. Lummox of a muttley middle-aged male? He’ll be lucky to get a handful even though the first dog really doesn’t need your shares and the second is the one who really, really does.

For me, I think this is why studies about shelter dogs haven’t been able to agree as to whether temperament or looks are more appealing, and that they can’t find a single thing that dogs could do to make themselves more adoptable, behaviour-wise. I think it’s why fearful dogs will find a home more quickly than aggressive-looking ones, as even though both are about fear, a sad looking dog inspires our positive affects, and an angry-looking one doesn’t. If a dog makes you feel pity rather than loathing, you’ll adopt it. If you feel warm rather than cold, bam, you might as well put your name on the adoption contract.

Trouble is, other things are at work that affect whether we feel warm or cold towards dogs.

Pedigree is one of those things and it works in a variety of ways. Partly because of how we view breed dogs as “pure-bred” and say things along the lines that we know their heritage and their behaviour will be predictable, that then affects how we view other dogs. I think that’s why some pedigree/breed or type dogs will leave soonest. I think that’s why other breeds like bull terrier breeds (or even terriers themselves) will stay longer because pedigree isn’t always experienced positively for humans, and because we bring a shedload of prejudices with us. For us in France, our hounds are seen often as ‘useful’ but ‘cold’ – they’re seen as outdoor, untrainable dirty, loathsome dogs who won’t bond with humans. It’s categorically untrue, but the chance of a French person adopting a dog like Jaguar (below) is very, very low.

In a shelter in France, he gets the contempt response, not the pity response. In Germany, where they don’t face such stigma, he’ll be gone in days. Especially where they know his story, which adds loads to his ability to make us feel sorry for him.

What we do know though is that dogs who’ve passed through a shelter or been rehomed are incredibly popular. There are a lot of warm and kind people out there who take on a dog they may not know much about or a dog who may have faced a lot of disruption. In France, by my estimates, at least 65000 dogs are rehomed every year and that makes them more popular than Aussie shepherds, Malinois, German Shepherds , staffies, Amstaffs and golden retrievers put together. The top 6 registered breeds in 2018 in France can’t compete with shelter dogs in popularity. I suspect that picture is duplicated in a number of other countries too.

There are differences, though. In the UK, for example, which has 9.9m dogs (estimated) to France’s 7.3m in a similar-sized population, our French shelter population is only the same size as the top two British breeds, the French bulldog and the labrador. These cultural facts make a difference: French people like “type” dogs, but breeds are clearly much, much less of a commodity here. In fact, four of the top six French breeds require registration to work (Malinois and GSD) or to avoid BSL (staffies and Amstaffs). You’ll see a number of yorkies or bichons for sure, but without paperwork to speak of. Work about your own national and regional demographics is vital if you want to understand what you’re up against as a shelter.

What else do we know about adoption trends from academic studies?

Surprisingly little, actually.

Most studies are done in the USA, Australia or the UK. Very little exists in Europe, and what I know of UK, German and French shelters is that there are enormous cultural differences. We need more studies about global shelter sizes, populations and trends. Until we understand demographics, we can’t compare countries or the specifics of particular systems. We can’t even compare ourselves with our neighbours.

We also know that the studies that have been undertaken fail to really show us anything in particular.

Most studies have focused on how dogs look or behave.

How dogs look has frequently been investigated as a factor behind why people choose a specific shelter dog, with variables such as size, coat length and colour, breed and age influencing adoption rates. I’ll just take you thought a handful…

Normando et al. (2006): young dogs adopted more quickly, gender not an issue

Posage et al. (1998): some breeds (terrier, toy, hound and non-sporting) are more successfully adopted. Light coat colours, small size and surrendered dogs from homes were also more popular.

Protopopova et al. (2012): breed type and small size determine length of stay.

Weiss et al. (2012): appearance in general was important for just 29% of dog adopters

Brown et al. (2013): young dogs and small dogs stay the shortest time in shelters. Coat colour and sex did not influence adopters. Guarding breeds stay longest. Giant breeds had the shortest stay. “Fighting” breeds were adopted surprisingly quickly.

Siettou et al. (2014): young dogs, small dogs, pedigree dogs and coat length affected speed of adoption.

Kay et al. (2018): age, coat colour and breed affect adoption rates.

Voslářová et al. (2019): coat colour influences length of stay and black dogs stay longest.

As you can see from this small selection of research about physical factors influencing length of stay, nobody agrees on everything. Sometimes things matter and other times they don’t. For us, small female bichons under two years of age will not stay long. Middle-aged big dogs of unknown heritage will stay an age (sorry Eden). Old dogs go quickly as long as they’re smallish and behave like old dogs.

Looking puppyish or like a juvenile also influences us, though studies were not carried out in a shelter (hence our love of squashed noses, oversized floppy ears and supersized bug eyes). Human coloured eyes might also influence our choices (like blue or honey-coloured eyes). Large eye size and inner brow movement have also been suggested to increase the appeal of dogs.

Despite this, decisions to adopt based on looks are clearly complex and no single factor studied has made us say “that’s the one!” Studies suggest that if a dog conforms to a certain type, they will be more easily adopted, but do not explain why results are often contradictory or complex.

We also have stereotypes about dogs in shelters which might not be true, like the black dog effect and do not address reasons why certain types of dog are over-represented in shelters in the first place.

Some shelters are following training programmes or enrichment programmes to increase adoptability by changing canine behaviour. A number of studies have shown that shelter staff and facilities may aid adoption. You know, nice spaces, helpful and knowledgeable staff. Even so, studies about in-shelter training or shelter enrichment programmes have shown inconsistent results and have failed to show a clear correlation with adoption rates. In-shelter research has mainly focused on how dogs can behave in ways more conducive to adoption such as lying down or engaging in play although a number of unpleasant behaviours such as jumping and mouthing were shown to be unimportant. Currently, the range of studies about behaviour have failed to demonstrate that teaching specific behaviours or changing the shelter environment would increase adoption.

All that scientific research!

For me, why they’ve failed to find patterns is because we fall in love quickly and it depends on how we feel about the dog. Do we have warm feelings towards them? Because if we do, we’ll be more likely to adopt. I think about Flika and how I think I may have left her had she not had a nosebleed on my foot. My pity levels shot up. And then, when she was here, she reminded me of my old dog Tobby. Not so much in looks but in personality and even how she moved. Warm feelings go up again. Now I’ve got myself feeling all gooey about old malinois as a result of my experiences with them, I then fall in love with them over and over. No longer do I feel contempt for those who shout at me from behind the bars, I just feel love and pity. I think that’s why so many people arrive having just lost a dog, as they’re not exactly lookin for a replacement, but we’ve got al kinds of warm and gooey feelings left over and we want to help another dog – maybe not one too like our last, but we want to adopt a dog to care for it in the ways we may not have been able to do with our last. Look at how mine went: lost Ralf suddenly and fairly traumatically, took on a dog I felt very little for (Tobby) but who needed a home, who then made me feel squishy about malinois and made me unable to resist Mrs Knickers. Compare that to the long, slow losses of Tilly, Tobby and Amigo, and caring for them exhausted me so much I didn’t think I had it in me to do it again. Four ageing dogs in five years has zapped my abiity to cope and then I take a younger one.

These narratives that lie behind people’s reasons to adopt a dog are worth listening to, not least because I do not think all people take shelter dogs in a commodity-purchase kind of way. The studies conducted have seen dogs as a commodity (what sells best? How can we test the product variability?) or the shelter as a distribution point (how can we market better, do sales better, help our clients better?) and adopters as customers. Now I think there are no downsides to better marketing, sales and customer relations, don’t get me wrong, and some people do want a second-hand/cheap dog.

But many others are deeply affected by their feelings towards a dog that may be influenced by but not ruled by breed or size or age, colour or sex or coat length. That’s why shelters have adopters who say “I’d like a young female spaniel” and leave with an elderly male German shepherd. The heart wants what the heart wants. Such adopters do not bear up to quantitative studies. You ask them and they try to justify why they picked the dog, but they can’t really explain why the homeliest dogs you’ve ever seen is one they find handsome or cute and loveable. It’s why adopters fall in love with the misfits and the grumps and the ones who look like they’ve been stuck together wrong.

People do fall in love with all kinds of unpredictable dogs that leave you wondering what on earth was going on in their tiny brain.

What I think this says for shelters is yes, you can obey the rules of marketing once you know your own shelter demographics, but you’ll also need to fight prejudice and contempt for some of your dogs. Sometimes, that will be your own prejudice and contempt too. I’m not a Jack Russell fan, and I know I need to fight my own feelings about cuties like this boy:

That affects us all: shelter workers who present their own favourites and ignore the dogs they feel negatively about, as well as euthanasia policies, marketing policies and adoptions. Sometimes, it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

I think it’s helpful for some of our dogs if we can move them to other shelters who don’t face the same stigma for certain types. We certainly make use of that to rehome our hounds.

I think it’s important to know that people may be governed by cultural preferences for dogs as a commodity, but that not everybody is. Every dog will have someone who makes them all gooey and some adopters are governed by very strong emotional affects like pity, love or empathy. I don’t think we should underestimate BOTH market factors that drive adoption of dogs-as-a-commodity, and emotional factors that drive adoption of others. Shelters definitely need their own data though, as it varies so very widely, but it’s worth understanding which of your client groups are driven by economical factors and which are driven by emotions. For some, a shelter dog is a cheap dog. For others, it’s the equivalent of ethical sourcing. In both, the shelter dog is a ‘second hand dog’ and whether that appeals to people for economy or ethics that’s worth understanding. However, a large number of people ARE driven by emotional affect to adopt a dog, and it’s worth bearing that in mind for dogs who fall into any of the studies’ “unhomeable” groups or if you don’t have a strong enough base of “ethical” buyers who are still driven by market forces but want an ethically-sourced dog. Someone out there somewhere WILL have warm feelings and knowing when to inspire pathos in your advertising and for which dogs is certainly a skill for shelters to consider. Woe betide you, however, if you as a shelter constantly go for the pity factor, as you’ll soon find yourself inspiring cold and incompetent feelings when people suss that this is what you’re up to. Save the emotional appeals for where they’re needed and your client base will trust your competence.

Next time, I’ll take you through prejudices and stereotypes that shelters themselves have to deal with and how they can do that.

Some of the studies mentioned:

Brown, W. P., Davidson, J. P. and Zuefle, M. E. (2013) Effects of phenotypic characteristics on the length of stay of dogs at two no-kill animal shelters. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science 16 pp.2-18.

Fratkin, J. L. and Baker, S. C. (2013) The role of coat colour and ear shape on the perception of personality in dogs. Anthrozoös. 26, 25-133.

Kay, A., Coe, J. B., Young, I., Pearl, D. (2018) Factors influencing time to adoption for dogs in a provincial shelter system in Canada. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 21(4) 375-388.

Normando, S., Stefanini, C., Meers, L. et al. (2006) Some factors influencing the adoption of sheltered dogs. Anthrozoös. 19, 211-224.

Posage, J. M., Bartlett, P. C., Thomas, D. K. (1998) Determining factors for successful adoption of dogs from an animal shelter. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 213, 478-482.

Protopopova, A., Gilmour, A. J., Weiss, R. H. et al. (2012) The effects of social training and other factors on adoption success of shelter dogs. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 142, 61-68.

Siettou, C., Fraser, I. M. and Fraser, R. W. (2014) Investigating some of the factors that influence “consumer” choice when adopting a shelter dog in the United Kingdom.Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science. 17, 136-147.

Waller, B. M., Peirce, K., Caeiro, C. C. et al. (2013) Paedomorphic facial expressions give dogs a selective advantage. PLoS ONE. 8.

Weiss, E., Miller, K., Mohan-Gibbons, H. and Vela, C. (2012) Why did you choose this pet?: Adopters and pet selection preferences in five animal shelters in the United States. Animals. 2, 144-159

Voslářová, E., Zak, J., Večerek, V. and Bedanova, I. (2019) Coat color of shelter dogs and its role in dog adoption. Society and Animals. 27(1) 25-35.