** and walkers, runners, cyclists, skateboarders and people on scooters too

The universe conspires, sometimes, to put themes into my head. A message from a friend of a friend asking about jogging, writing up a case study about territorial aggression and an accidental encounter with a jogger kind of all came together.

We risen apes, we humans, we hairless bipeds, we monkeys, we’re different than dogs. There’s a surprise. Our nearest living relatives are chimpanzees and bonobos, and up until around 13000 years ago, we lived in similar sized social groups to our genetic cousins. Mostly, that was about small social groups of up to 20 people who lived together, stayed together and occasionally split up for foraging or reproduction, then to come back together again.

Madness. 13000 years ago and that was our mode of living.

But then we changed. Our human brains had already been evolving. Part of that evolution meant handling bigger groups of up to 130 or so. We started to form clans. Mostly we’d live apart, but we’d come back together for special occasions. That meant greeting people you mostly already knew. You were kin. Your old Aunt Edna had married some bloke from the village over the big hill and you might only see her 4 times a year at special events. But you knew her. And you knew that bloke too.

Even when we moved into autonomous villages with bigger populations – and bearing in mind most of the world’s population weren’t doing that even 7500 years ago – you still knew most people. Friends of friends. Relations of Relations. If you were born in the UK or Ireland even 2500 years ago, you probably still lived a life in a village where you knew everyone.

Bring on the change to city states and nations, great cities of Ur and Jericho and Nineveh, and you’ve not a chance. You have to handle living with people you don’t know. Lots of them. And that’s so hard we needed to invent laws and religions and consciences and social codes and all sorts just to be able to handle how hard it is to live with loads of people you’re not related to.

And at that point, we moved out of mammal territory, right into the Anthropocene – the Age of Man. We leave our mammal relatives and codes behind and within a geological blink of an eye, we forget a lot of what we once knew until we’re really fighting for our lives.

With all our social codes, we forgot how hard it is to split up (fission) from the group and to come together (fusion). Most mammalian species do not do this. Not repeatedly and definitely not with big numbers. Another thing happened too. With farmers doing all the agricultural work and the rich keeping hunting for themselves, we forgot what it felt like to be a predator. We forgot how easily the world around us spooks. We grew up around cats and dogs and goats and sheep and we forgot that it is not normal for the lamb to lie down with the lion.

We forgot.

7500 years and we forgot what it feels like to be a predator.

We forgot how delicately you need to move towards things in order to catch them. We forgot how to sneak, to hide, to move slowly, to pounce. We forgot what happens when you take your idiot Uncle Kevin (married to Aunt Edna over the hill) out on a group hunt, he sometimes charges at a deer and spooks it and the game is over. No supper for you, thanks Uncle Kevin. Clumsy oaf.

We also forgot how every single thing outside our direct social group is a threat. We forgot how it is to be suspicious of everyone but the 20 people you know. We forgot how it feels when someone of your own species runs at you.

We’re unlike every other mammalian species in that respect and we forgot how it all operates out there in the big wide world.

The San bush people in Africa classify the animal world in three ways: edible, threat and non-edible/harmless. I like to think animals might classify other animals in the same way. Can I eat you? Will you kill me? Do you taste bad and you’re no threat to me? Are you prey / predator / other? I wonder if dogs work in the same way? Can I eat you? Will you kill me? Or are you nothing of interest?

Well, we remember when we’re around other species under pressure that they think of us as predators. We don’t expect to walk into the rainforest and be greeted by gorillas saying, “Welcome! Snacks at 5. Drinks on the terrace before supper!” We don’t expect to run through fields and blithely expect all the sheep to continue merrily eating their way across.

Run at a bull and you’d be the least surprised person at the planet if the bull dipped his head, lowered his horns and ran at you like the pure-blooded predator you are. THEN, you’ll remember your 4 million years of hominid existence, that innate knowledge will awaken from the depths of your subconscious mind, and remember that, outside your own species, pretty much everything else on this planet thinks of you as a threat.

There is not a walker or a jogger alive who doesn’t know how a bull might feel if we ran at it. Just because you’re a prey species doesn’t mean you don’t fight back. And just because you’re a predator doesn’t mean other predators don’t scare you. Don’t make me remind you of how we feel as a species about sharks and man-killing tigers.

So we know that we can’t run at bulls, lions, tigers, leopards, rams, billygoats, gorillas, bears, wolves and chimpanzees, pigeons, wasps’ nests or even angry swans. We know this stuff. We spend all our time fretting about being eaten by sharks instead of bitten by mosquitoes – one of which is thousands of times more likely to cause us serious injury or kill us. We know if we run through Trafalgar Square, we’ll set the pigeons flying. We don’t expect animals to say, “Yeah, bud? Nice run? How’s your heart rate”

Yet we come to dogs (and also cats I think) and expect them to play by human rules when they are an animal. An animal who lives with us, sure, but an animal who is 100% animal and hasn’t forgot that stuff running at you probably means to kill you. It’s sitting there in their primeval memory waiting to pop out when you startle them. It even comes back to you too when a dog charges at you. Suddenly, your primitive old ape brain says “Run!” and you do. Exactly the same for dogs. Except we are so very, very human-centred that even though that dog might startle and scare US, we can’t possibly comprehend that we just might have done the same to them. Talk about a need for empathy….

Dogs ARE different than bulls in that they are much more used to our human ways, interlopers as they are between the animal world and the human one. Many dogs will blithely accept your sweatpants and your yoga pants, your neon trainers and your waterbottle obsession.

What about the times they don’t? Part of it comes down to poor socialisation and lack of exposure. For dogs who aren’t taught that people do insane things like cycling, jogging and walking with weapons (aka walking poles) then they just haven’t learned that people might do such crazy things. Then, woe betide both of you if you startle them the first time they learn about such things. My dog Heston is like that. We have literally seen three joggers in a year. People just don’t run at us. Normally we see no joggers in a year, but lockdown put paid to that.

Some of it, even with very well socialised dogs who are used to jogging, scooters, cyclists and pram pushers, is about the startle response.

The startle response is that primitive mechanism that takes over when predators run at us, too, or scary big edible things that could kill us, like bulls. We still have one. So do dogs. Don’t tell me, if you are a jogger or a cyclist, or even a walker that you have never come up behind someone and given them a bit of a shock. Unless you are very bad at jogging and you pant like you’re in the process of dying, you’ve probably made at least one person jump, right?

The startle response is heavily implicated in fear learning, which is the best and most successful learning of all. Take that, Hamlet. It wasn’t your fault I couldn’t memorise more of you for my A levels and that practically all of you has vacated my head (or at least all the neural pathways have died). It was just because I wasn’t afraid. The tiny amygdala takes over with fear learning sending very loud and immediate messages to the hypothalamus which controls all sorts of things, but most importantly the fight-or-flight response. Nothing controls the hypothalamus like the amygdala. The amygdala says “run!” and the hypothalamus doesn’t even ask how fast. It just says, “Yes, Chief!”

So there’s that.

Whilst the lovely, rational, sensible, evolved (and very small) neocortex of a dog is explaining that it’s nothing to be afraid of and humans don’t mean to kill them, the amygdala has already tripped the fight-or-flight response.

Fear learning has been so crucial to mammalian existence these last 50 million years that our lovely brains have made it the best learning of all learning. It’s why PTSD is so bloody hard to overcome and why scary experiences are so much more powerful than everything else. Like I’m here desperately trying to remember facts for an assessment and my brain is going, “Do you remember that time when that tramp ran out of the barn at you all?”

When fear has been involved in learning (and we’ve survived – fairly crucial) then we are sensitised to the same stuff happening again.

That’s often what happens with dogs. Especially youngish dogs who had never experienced a jogger before. The first one might have startled you and frightened you, and then you spend the rest of your walks for the next year thinking a jogger might leap out at you.

And you joggers with your lovely silent shoes and your headphones and your lycra that makes no sound and your efficient breathing and your bloody great speediness… if you haven’t made at least one person jump that you’ve run up behind, you’re probably just not trying hard enough.

So when a startle response is involved, then it’s very likely the next time a dog hears someone come running up behind him, he’ll go straight into angry defensive behaviour. And if it happens often enough, they’ll start listening out for you. This is especially likely if the dog is on a lead or the dog is on their territory or the dog is near their human. All three take that flight-or-fight response and rule out the ‘flight’ bit. Whether territorial behaviour or the lead or even the emotional bond they have with their guardian, it’s strong enough to make ‘fight’ the only option.

The problem is the whole “running towards”. Just as we can’t understand (and I count my former marathon-running self in here) that dogs might be as startled as we are, and afraid, we also can’t understand that we might actually slow down. It’s like it doesn’t cross our tiny minds to slow down any. In fact, if anything, we speed up to get past quicker.

Because that helps as much as pouring oil on flames.

Whether you sneak up from behind, or you come barreling in head first, you’re still an apex predator running at something much smaller than you who doesn’t have the faintest idea that you’re just trying to lose a few pounds before Christmas. Chimpanzees, and let me be clear on this, do not go running unless, you guessed it, they’re after something. Wolves might track and pace, but you see them running directly at you and you’re probably a deer that needs to think about bolting right about now.

So first let’s have a little empathy and understanding for the species around us that haven’t yet got their head around the whole recreational aspect of human behaviour. Understanding why dogs sometimes react badly to people running or moving, especially towards them, is to begin to understand why you might get into trouble.

Second, know how to deal with it when you do.

I’m going to get absolutely serious for a moment. If you continue to run at a dog who is already alarmed, do not be astonished if you get bitten. If you walk too close with sticks and weapons and you just keep approaching, with a smarmy, self-righteous “right of way” thought in your head, you’re very likely to get bitten at some point. Just as you’d be likely to get head-butted by a goat or gored by a bull.

And yet you still do it.

Yesterday, I saw a guy running straight down the road at us. I’m going to stop saying ‘towards’ as that’s a very human word. I knew he was jogging. He was wearing lycra. Clue number 1.

This is what a dog might see…

Yep. You are Pennywise the Clown just running right as us.

Now I try to be a good citizen and I know dogs and joggers. I try to get out of the way, but that means literally stepping into a cornfield and not as much distance as I’d like. Joggers and cyclists are often moving so fast that they don’t give dog time to get out of the way.

Does the guy slow down? No. Does he move over in the slightest? No.

Now he’s a nice guy and he’s a neighbour who obviously thinks jogging is a good way to pass a Saturday. So be it. But I’m the one trying to manage animals and I’m the one changing MY behaviour.

So I say this with kindness, but I’m serious. Change your behaviour and stop selfishly fixating on your run or on keeping up your pace. So you slow to a walk for five minutes – or, heaven forbid, you jog on the spot a little. It won’t kill you.

Instead of sticking to your guns and thinking about you and your run, shift your thinking just a little and it’ll be easier for everyone.

That said, I do understand what it is like to run through a dog’s territory, to run past people with dogs on leads and how scary it can be if you feel like you’re not safe.

So now I’m going to give you some tips as to what you can do, what you could do and what you might do in three different situations if you feel a dog might attack you if you are running or walking. These three situations include off-leash dogs who are running at you and look like they might attack, dogs on home turf whether they are fenced in or not, and moving past people who have got their dogs on a lead.

First. Dogs on leads.

Dogs on leads have nowhere to go. They are literally attached to someone who often doesn’t even realise that their dog can’t cope. Not every guardian will take their dog into a maize field so you don’t have to slow down. Dogs on leads can’t run away and so out of fight or flight, that dog has one option as you approach. Slowing down might take the threat off, but even walking towards an alarmed dog risks a bite, so the best thing to do is find somewhere to screen yourself from them and wait for them to pass. Stop by a tree and do some jogging on the spot. Take it as a moment to pop onto the other side of a parked car and do some burpees or full bastards if you don’t want your heart rate to drop. Don’t do those, of course, if you haven’t seen a doctor recently or if the people and dogs are passing at that moment. Burpees are WAY more alarming than joggers. The main thing is not to continue on that trajectory directly towards them if the dog is already barking and alarmed. Change your route temporarily. Take five minutes to do some on the spot. As soon as you are out of sight, the dog will relax.

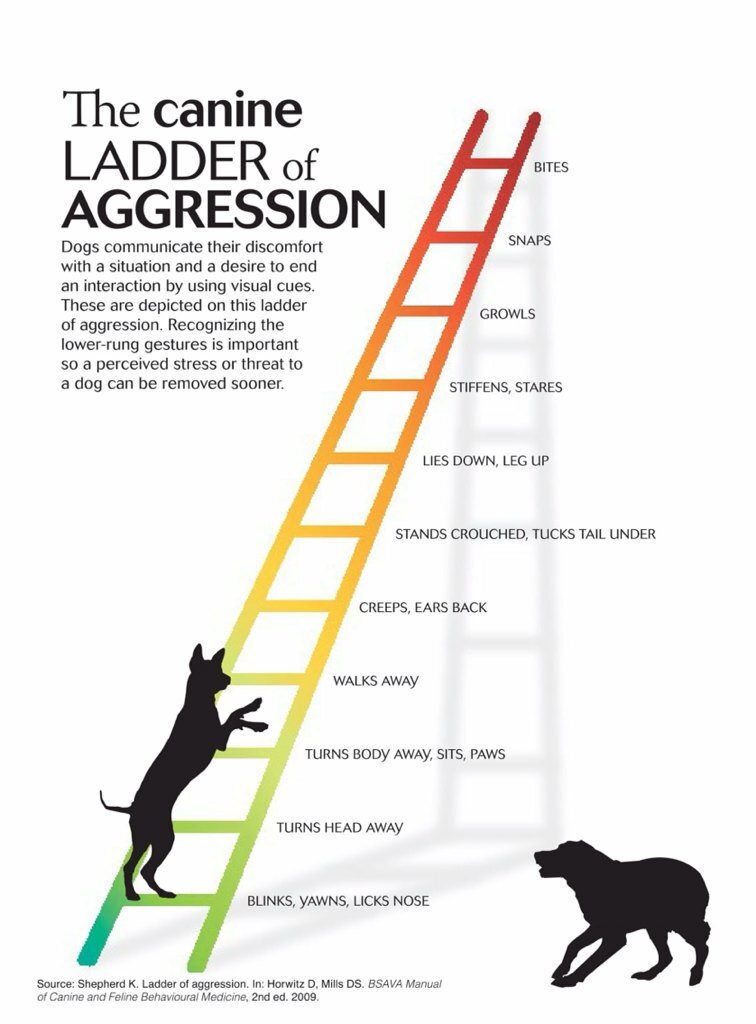

This excellent guide from Dr Kendal Shepherd gives you signs to watch for. If you see a dog slow down or stiffen, good chance it will escalate if you keep running towards them. If they’re barking or growling and you keep going, then snapping, snarling or lunging will likely be next. Don’t think that once you’re past, you’re safe. Plenty of joggers get nipped on their backside and plenty of cyclists find their bikes get bitten on the rear tyre.

Under no circumstance run within the distance of the lead and the owner’s arm and the dog’s mouth. If the lead is 2m and the owner’s arm is 1m and the dog’s head is 25cm, then know you need to be at least 4m away at all times, and probably more since they could lunge. If you absolutely have to run past (and really, do you?) a dog who is already standing like an enraged Cujo, make as much space as you possibly can.

It is absolutely possible for you NOT to continue your jog for 2 minutes. It is absolutely possible for you to let them pass.

Want more? Don’t eyeball the dog (you wouldn’t eyeball a bull… tell me you wouldn’t eyeball a bull!) keep your gaze averted, body at 45° from the dog, be slow and still and wait until they’re at least 10m past you until you move again.

And once you’ve passed, say thanks. That dog owner standing in a ditch with two big German shepherds has put a lot of work into getting them like that. They’re also stopping so you can pass. It’s just rude to keep going as if you don’t even give a stuff. Yesterday, my neighbour was very chatty and decided to stop 5m on the other side and jog on the spot. Don’t do that either. A simple thank you and a smile from both sides would be just lovely. Remember that 13000 years we’ve just had as a species? It was engaged in learning this.

Second scenario. Dogs in yards that aren’t attached or may come over a fence to get you… don’t think that you’ll be able to run up to them and just run past. You are literally threatening their territory. You don’t stop being a threat just because the dog is behind you.

Beautifully trained attack dog here, but ALL dogs can do this and if you carry on running, your motion sets off all kinds of other primitive hardwired patterns. If you’re running up to what a dog considers his territory, you don’t get to have property law discussions about where the boundaries are. Like it or not, we bred dogs to be territorial because our ancestors thought that would be kind of cool some 5000 years ago. We purpose-bred some dogs for that exact behaviour. If you lock your house to guard it from intruders and would take offence at people traipsing through your garden, please don’t judge a dog for guarding his home from intruders.

If you really feel that the dog is escalating in behaviour, slow down and back off. Don’t turn your back on the dog, but know that the dog is unlikely to come off his or her terrain if you’re no longer advancing. I know one or two dogs who might come over property lines but most dogs will make very big and noisy displays if you are coming towards their property (the same if you run at them) and they just want you to stop. When you do, then they don’t need to keep doing it any more. Territorial behaviour is about a threat to their territory, and once you stop being a threat, then the behaviour subsides. If that means you have to get your phone out and choose another route, so be it. It may save you from a very nasty situation.

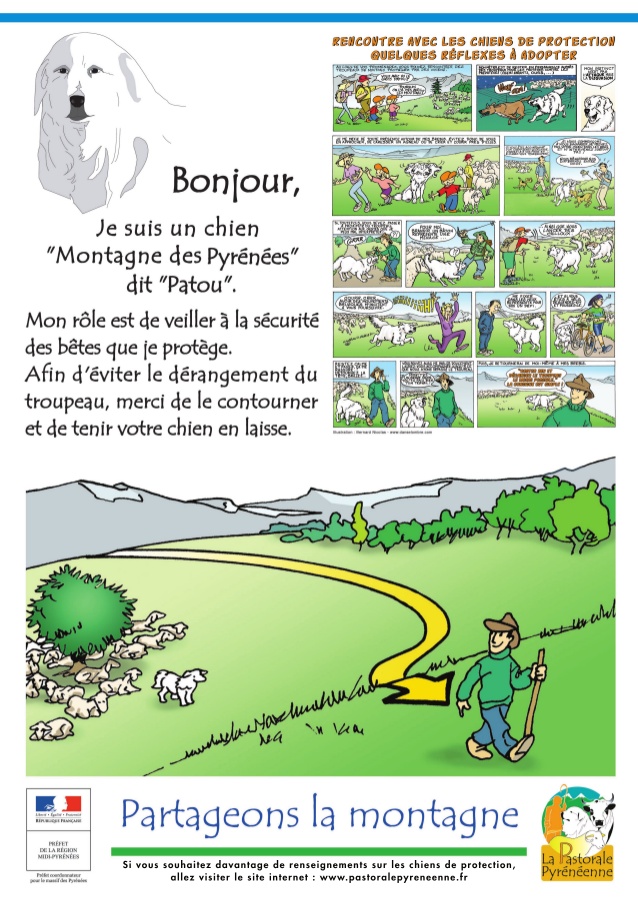

By and large, the situations I deal with where dogs have bitten or tried to bite joggers, walkers or cyclists have been because you’re near their territory or they’re on the lead and the human attached to the other end didn’t read the situation well enough to keep you and their dog safe. Or you got much closer than they could have anticipated and can’t manage their dog. Some – very rare – dogs are also protective of their guardians and might issue a silent bite as you pass. The situations you should be most able to cope with as a jogger are dogs on leads, dogs not secured in gardens and dogs who are with guardians. But you may still be worried about loose dogs running at you if you are running. Round here, it’s kind of rare, but go 300 miles further south and you may find the formidable Chien de Montagnes des Pyrénées or Pyrenean Mountain Dog also known as the Patou. These dogs who look like polar bears got busy with golden retrievers are there to protect the flock from wolves, bears and men. You’ll often see signs that they are working, and information about dealing with them.

What is says is essentially this:

* Do a U-turn or make a very wide arc. The same is true with a loose dog who doesn’t seem to have a human attached.

* Don’t scream, shout, flap about or panic.

* Don’t wave a stick at the dog or a walking pole – it’s an act of aggression.

* Likewise with throwing things.

* If you run away or towards, both actions will likely incite the dog to engage with you.

* Don’t stare at the dog.

* Turn slightly away, continue slowly, staying calm and passive.

In the thousands of dogs picked up by our pound every year, all loose, the only time they bite is if they are approached and someone is trying to restrain them. That also doesn’t happen very often. Loose dogs, off territory, without owners, in full daylight (don’t jog in the dark like I used to – that’s just silly) are not likely to be that bothered by you if you don’t bother them. Slow down, turn away, stop running and arc away from the dog if you absolutely have to pass them.

Sadly in my work with dogs, I do know dogs who’ve bitten both joggers and cyclists. It’s usually that rare combination of circumstance: the owner was coming out of the house with the dog and the jogger was just there… the owner came round a corner and found themselves face-to-face with a cyclist. Sometimes, it’s stupidity on behalf of naive owners who get a rude wake-up call because their dog isn’t as capable as they think they are. Other times, it’s because joggers have determinedly tried to run too close to dogs. One jogger I know got bitten because he ran through a group of people walking their dogs on a social activity. I don’t do victim blaming but I struggle to think of many dogs that I’d 100% trust to have a stranger run less than a metre from them.

You may think about carrying deterrents like airhorns or pepper spray, a spare lead or whatever, but I’d advise you not to. If you’re thinking like this, you’re thinking of running too close to dogs still when really you should be aiming to understand that it’s your behaviour that’s triggering the dog and that small changes for a few minutes will reduce your risk to zero in most cases. This is not to say that you’re giving in to dogs who should have been better socialised or should have had better breeders or whose owners are idiots for thinking a walk around joggers and cyclists is something their dog can cope with. See the dog as an angry bull and you’re probably going to find it a lot easier to remember what to do.

Hopefully that helps. It’s not to say joggers are demons or that dogs are bad, just that life is what it is and we all need to live harmoniously. I’m a big fan of both joggers and dogs. But I know how scared you both are of each other.

And if you’re a dog guardian reading this and you know your dog can’t cope with moving people or machines, get in touch with a qualified trainer.