No, I’m not talking about wafer-thin ham or lion cuts in grooming, I promise!

One of the things I find to be absolutely true is that guardians have already tried to do what I’m proposing. I never turn up and propose something they’ve never considered. If they have a dog who’s wary of strangers, they’ve tried to expose their dog to strangers. If they have a dog who barks when people come in their house, they’ve tried to expose their dog to people coming into the house. If they have a dog who’s chasing cats, they’ve tried to expose their dog to cats.

And so it goes.

So when I say we’re going to try it again, they’re all: ‘Tried that. Didn’t work.’

The main difference between what I’m proposing and what they did is that I’m going to do less of it over a longer period. Much less of it. Much longer period.

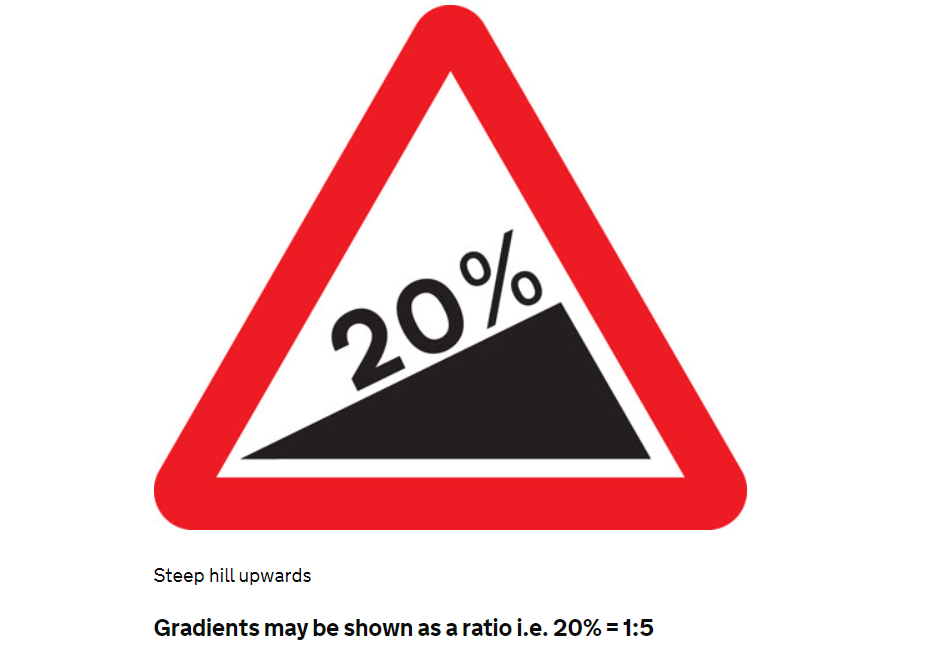

When we’re working with dogs to expose them to things they find exciting or frustrating, or when we’re working with them on things they are afraid of, then we use a planning tool called a stimulus gradient, like those road signs you see to show you inclines and declines.

It means instead of exposing our dogs to things they’re scared up right up close, we’re going to take our time and work further back. We’re working either to train them and teach them new skills, to desensitise them or to counter-condition them. We can, of course, do all three.

So why am I doing exactly what the guardians have already done, knowing that it will work?

Basically it comes down to understanding and expectations.

Lidy, the recalcitrant malinois, has recently discovered pigeons. We’ve never known pigeons, other than the wood pigeons that lived in the garden and were much more wary of other species. At the moment, we’re living among cocky, well-fed pigeons who have never met a Lidy. She’s never stalked birds, but now she’d decided she’s a pointer, she’s in full-on stalk mode around 200m away.

Now we will be working on this once life settles down for us again. Right now, we’re just getting by.

When I start working on her with it, though, that gradient will be so gentle and so ridiculously slow. We’ll start over 200m away, where the sudden flight of a flock of pigeons isn’t likely to set off all her chase mechanisms.

Where most guardians start, though, is when the dog is so aroused that they’ve no chance intervening when the pigeons all decide to fountain up into the air. Often, they will tell me that they’ve had loads of space. And when I ask them how much space that is, it turns out to be 10m or so.

Not only that, but they’ll also lump the distance and increase the challenge too significantly. I may well do a couple of days around 225m and then 210m for a couple of days. This is shaving. Slicing off such fine, fine tranches of the distance that it may seem barely noticeable.

Generally, I tend to work between 5% – 10% off the gradient. Any less and progress will be frustrating. If I’m doing 3%, for the sake of argument, over 225m, by day 21, I’m going to be around 125m away still. It could take me 3 months of diligent work. For most guardians, that can be very frustrating. It can also be frustrating for the dog too.

Yet most guardians shave off too much distance or add too much time. For instance, even a 25% gradient will take you 17 days, shaving off 55m on that very first day, and if I’m working on Day 1 at 225m without reaction and I dip down to 170m on Day 2, it’ll be unlikely my dog will be able to cope with such a big dip, especially at the beginning. If she’s stalking them at 200m, I’d be silly to think that one day of training will be enough. The gradient is too steep.

In fact, most guardians aren’t always aware of the point at which a trigger becomes noticeable. We call this salience. Last night, hot night, windows open, some neighbours were out late in the garden drinking and chatting. I was trying to drop off to sleep. Most of the time, their voices were background noise, and once or twice every two or three minutes, the decibels would increase. Background noise became salient.

Now I was a long way from yelling at them out of the window but two hours of spiking did test my patience. Yet most dog guardians do the equivalent of waiting until their dog is leaning out of the window yelling obscenities. If you wanted to work on my tolerance of night-time noise, then waiting until I’m involved in blue-faced yelling about respect out of a window at one in the morning is never going to work.

So partly we have to notice that point of salience and work at that point. Not the point of reaction.

In other words, we want to know when the trigger becomes noticeable, not when is the dog out of control. The salience point for Lidy is around 200m. The out of control point is around 10m when the pigeons all decide to take off. That’s the first thing we need to do if we’re going to start shaving off thin slices: work out the salience point and the reaction point. When does it become noticeable? When does the dog react?

When we’ve got the point of salience, that moment the trigger slips from the periphery into relevance, that’s where we need to start the gradient. As you’ll know from my other blogs, that can often be around 500m sometimes.

But that’s where we start planning.

A stimulus gradient is basically like any other gradient. It can be steep or it can be really shallow. Our dogs’ exposure to things that excite them or things that make them afraid is most likely to fail when we expose them on a steep gradient. That 25% gradient is too steep. Even a 15% change gradient is too much for most humans involved in achieving goals – let alone a dog who feels murderous around pigeons. Think of us going down a steep hill in our cars…. We know the steeper it is and the more pressure we put on our brakes, the more likely they are to overheat and fail. The same happens to our dogs’ control mechanisms.

Making the gradient less challenging without making it frustrating is where the shaving and fine slicing comes in. The better we are at this, the more likely our dogs will be able to cope. Too big a gradient over too short a time and we’ll lose. Too small a gradient over too long a time and we’ll lose. We’re looking for the Goldilocks gradient: just right.

Once we’re working at the point of salience, not the point of reaction, and once we’re working on the Goldilocks gradient, the animals we work with will find life much easier.

Now I could take you through the complex maths and pyramid sets I do with clients, or the occasional variable sets that average out to the set increase for that day, but most of my clients find that too precise and overly complex. I find that, as long as they’re keeping an eye on body language and they’re working roughly around the Goldilocks level, things usually go just fine. It doesn’t need to be planned in compulsively inflexible mathematical steps. In fact, I think most of my clients would give up if I expected this. That’s not to say I don’t expect journals and logs along with rough estimates of distance, but I don’t expect them to get their measuring wheel out, glue some pigeons in to place, measure out exactly 169m, do five trials that average out to 169m and repeat the next day at 162.5m. That’s where frustration lies.

I have found, though, two other techniques that can help. The first is to keep to a short number of trials.

I know people who’ve shaved their gradient so finely that they’re doing eight months on a programme. Not only that, they’re starting at reaction point, not salience point, and they’re still battling the dog eight months in. If you’re doing it at that beautiful sweet spot, you’ll find that five trials that finish on a win is more than enough.

You don’t need to be doing twenty or thirty minutes. Everything we know about Pavlovian conditioning says that associations should happen within a brief number of trials. We do five trials and we go.

Of course, my clients think this is madness at first. We rock up, we do five trials, we go home. What kind of trainer is this?!

And this is why I need them to be able to do most of it themselves. I don’t expect to have to go and hold their hand over this once they know where the dog notices the trigger and they’re making sure their next-day goals aren’t some enormous and unreachable challenge.

We turn up, we do five trials. We go home.

Dog working on fearfulness around people? See five people, go home.

Dog working on predation of pigeons? See five flocks of pigeons, go home.

In fact, it may even be five repetitions of the same trigger. That’s fine too.

That’s my first piece of advice. Keep training sessions ridiculously short.

My second is to finish on a win.

Humans are terrible at pushing things too far. We always do it. ‘Just one more!’ we think to ourselves. Our hardest habit to break will be getting over that just one more mentality. When we finish on a loss, not only is the dog rehearsing a behaviour once more, but they’re also strengthening the link between doing the behaviour and what comes next. One loss and we’re then fighting to try and get a win. What happens if we have to go through fifty repetitions to get that win? We’re at 50:1 in terms of practising vs learning. I want zero practising.

So when I finally get around to working with Lidy on her pigeon fancying, we’ll be doing those four things: starting at the point of salience where she notices them, not when she’s leaping after them… planning a ‘Goldilocks’ gradient to make sure I’m not asking too much or too little… keeping sessions short… finishing on a win.

Once those four rules are in place, the progress made is astounding. Those four rules are the difference between trying a technique and failing, and trying a technique and succeeding.

In other news, my new book came out on Saturday. It’s a book for trainers who are looking at ways to increase client engagement. If you’re a dog trainer who wishes that you just had to work with dogs, because they’re easy, but their humans are a challenge, this book is for you!

Find it on Amazon or click the image!

If you’ve ever felt like you know how to train dogs but you’re missing out on key skills on training people, if your clients testing your patience with their weird and idiosyncratic ways, then this book is made for you.

‘Owner compliance’ is often seen as the magic ingredient where successful outcomes are concerned in dog training. Yet the concept of force is at odds with how many of us work with animals in a compassionate and cooperative way. In this book, you’ll find 30 lessons to sharpen your skills in taking a compassionate and cooperative approach with your human clients too. Make no mistake, though: it’s not tea and sympathy! It will also give you a business edge too!

Client-Centred Dog Training by Emma-Jane Lee: Out Now!