In the last post, I took you through the essentials of respondent conditioning. We looked at how our brains streamline sequences of events to help us predict what will happen next and prepare us for these events. I took you through some common examples and explained how these associative learning mechanisms help our bodies prepare for things that will happen next.

Just to recap…

By and large, the method of respondent conditioning is how many troublesome behaviours start in our dogs in the first place. A certain feline smell comes to predict the presence of said animals, perhaps preparing our dogs for an exciting game of ‘spot the cat’ or ‘chase the cat’. When I had cats, Fox and Bird would often turn up miaowing. That miaowing came to predict yummy cat food leftovers for my dogs, and so my little cocker spaniel became delighted by the sound of my two ginger reprobates showing up first thing in the morning. Later, when I lived with a house-bound blind cat, the sound of him scraping his litter box, and, inevitably, the scent of freshly laid cat turds meant the all-you-can-eat hot cat turd buffet had just opened, and my irrascible little cocker high-tailed it to the litter box, as surely as if a bell had rung to say it was lunchtime.

It wasn’t all about food, either. Neutral signals like a cat miaowing or a scraping of litter came to predict the presence of food, for sure, but they also come with emotional valence. That’s to say if you find freshly-laid cat cookies yummy, then the sound of scraping will come to elicit a positive emotional response too. And if you are trying to stop your cocker spaniel eating cat turds and harassing your blind cat, then the sound of cats scraping in litter will come to elicit a feeling of dread and disgust.

Much of the work of dog trainers is about reducing the effects of this respondent conditioning. Dogs who are over-excited by a walk or by a food bowl can be troublesome. Being ruled by our emotions makes us forget our learning, and so it’s not unusual to find dogs struggling to cope with very basic instructions when their heart is ruling their head. Likewise, the sign stimuli that provoke predatory behaviour like absconding to chase a deer or a hare can be the very bane of your existence if you’re working on recall.

Other times, the emotions elicited by those stimuli can be negative ones like fearfulness. A dog who has learned to be afraid of car journeys or muzzles because they predict vet trips, a dog who has learned that the sight of the lead predicts a loss of freedom or a dog who has learned that hands coming towards them when they are restrained is a dog who knows exactly what will happen next, and may take some evasive action to avoid said events.

As we know from the previous post, these emotions are elicited. That’s to say there’s as much chance of your dog being able to switch off those emotions as there is for me to switch off happy feelings when I eat cake or see blue skies or smell suncream or to switch off bad feelings when I see an email from the tax authorities. Whether they are simple reflexes or they are more complex action patterns, the power of an unconditioned stimuli is not just hard to ignore: often it’s impossible to ignore. Likewise, conditioned stimuli can be just as powerful. You can’t tell someone with a PTSD response not to have an attack; you can’t tell someone having a panic attack just to calm down. In fact, much of the continued work on respondent conditioning in humans is looking at its role in overdoses, in addiction, in PTSD and in phobias or panic.

Overcoming respondent conditioning

Human therapies can move on in ways that animal therapies cannot because of one simple fact: language. We know humans can use language to elicit memories in others and we can also use language with ourselves to change things. Some of the work on reconsolidation of memory, for instance, asks you to recall a time when you felt one thing or another so that then the therapist can work with you on reframing that memory. I do a lot of this with dog bite victims. I can’t ask dogs to remember things and I can’t work in the same ways and with the same breadth as I do with humans.

This means that those of us working with species with whom we cannot communicate are stuck working with some techniques that seem a little dry and dusty to human therapists. That’s not to say these are not useful techniques or that animal emotional and behavioural modification hasn’t moved on, just to say that the communication barrier makes it harder to change how animals feel about stuff that excites them and about stuff that makes them afraid.

Respondent counterconditioning found its beginning with a student of John Watson’s, Mary Cover Jones back in the early 1920s. She worked with a number of children who had fears, including one boy who had a fear of rabbits. She paired up the rabbit with food, gradually moving the rabbit closer to the boy as he ate. Originally, she called this ‘direct conditioning’ but it later became a foundation stone of what counterconditioning would become: taking something that had already been learned by respondent conditioning and pairing it up with an unconditioned stimulus of the opposite valence.

What does that even mean?

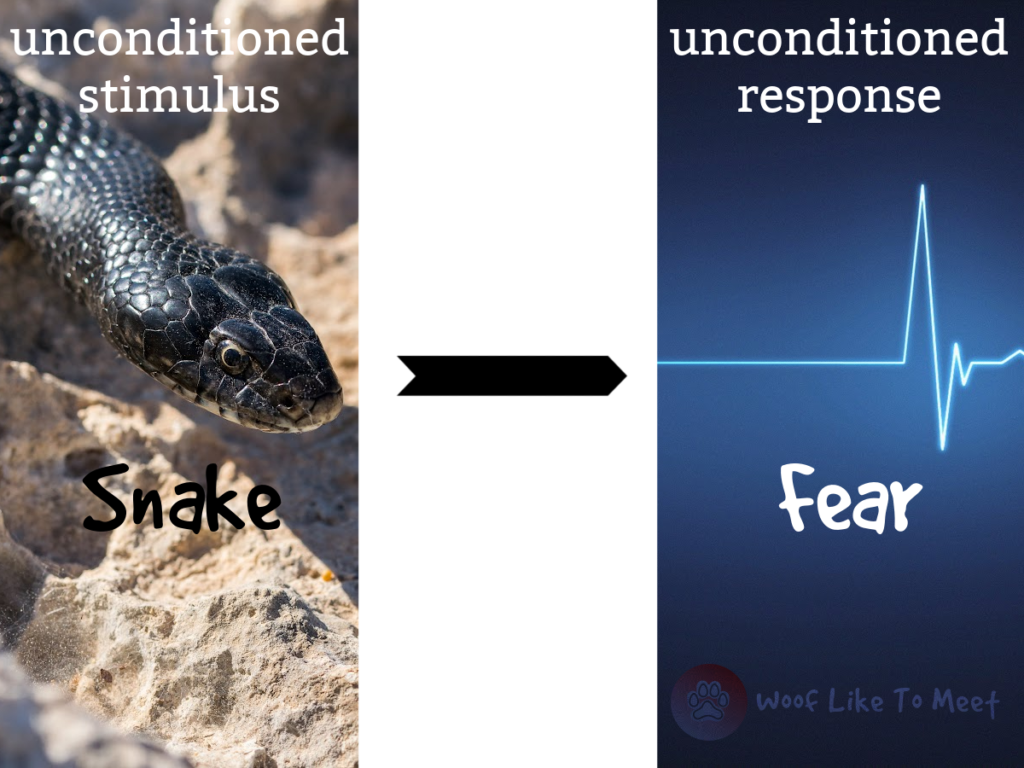

Well, as you learned in the last post, there is stuff we’re born liking, usually that meets our basic physiological needs like food and safety, and there is stuff we’re born not liking, such as pain, nausea-inducing stimuli and disgust-inducing stimuli. Some stuff, as you read, is actually fairly easy to condition.

You simply pair that up with things we’ve learned.

For instance, and I kid you not, when I was an early dieter back in the nineties, some therapists were working with forms of aversion therapy to make food less yummy. One thing to do would be to imagine your favourite food, and then to imagine something disgusting straight after. Like pizza? Imagine it with slugs crawling on it. Like bacon? Imagine the scenes of slaughter that put it on your plate. Like chocolate cake? Still feel the same if you know it touched dog turds? Honestly, I was put off Weetabix for good by the boy over the road telling me they were made with elbow scabs and crusty snot.

Aversion therapy sadly still has its fans in the human world and has been used in long-term captivity and brainwashing as well as in so-called conversion therapies. It also still has its fans in the dog training world, with people who try to use shock or pain to stop dogs chasing things. One old-fashioned treatment to stop dogs chasing creatures was to tie the dead creature around the dog’s neck. I’m guessing the principle at work was trying to make the dog feel nauseated by the smell in the hopes they’d never chase the thing again.

Do they work?

Not often.

Why can respondent conditioning be so tough to change?

The problems with respondent counterconditioning are manifold, not least that we don’t actually really know what it is doing and we also know that respondent conditioning in many circumstances can be surprisingly resilient, as many addicts will attest.

For instance, respondent conditioning can be spontaneously recovered. What that means is that if you give it a gap between extinction or counterconditioning protocols, it’s likely to pop back up. I had many years of extremely healthy eating after learning to rely on chocolate and junk food in my teens when I needed a pick-me-up. What happens when an unpleasant situation re-occurs after years? Boom. Back to relying on chocolate and junk food. Healthy eating is a conscious process for me; eating junk food is an unconscious habit I return to time after time when my brain is occupied by other things. Time is not kind to attempts to remove that original conditioning.

Respondent conditioning can also be renewed. What this means is that if you go to a new place, the old associations can pop right back up again if you did all your behaviour modification in a different place. This is especially relevant for animals whose learning is so much more contextual than ours. In other words, if you are working on processes with your dog to change their behaviour towards cats, bikes or human beings, don’t expect that learning to be as solid in a different venue. Really, what I’d say we’re doing when we engage in processes to change a learner’s feelings about stuff is we’re teaching them exceptions to the rule, little by little. Oh, not that one. Oh, not that one either. I’ll explain why I think this shortly, but suffice to say that respondent conditioning can easily be renewed when you go to a new place. My dog had a phobia of one vet to the extent of I went to another vet. He was absolutely fine in the second vet for years and years until they did the same thing: lifted him onto the table. And that phobic, panicked response was right back again. You might, therefore, think you are in a new environment – and you may well be! – but if the dog doesn’t have the same stimulus – in this case, being lifted onto the table – there’s no reason for the emotional response. And another vet was ruined.

This may actually be a better example of a reinstated response. The dog met the unconditioned stimulus again and the uncontrollable fearful response popped right back up again.

Respondent conditioning can be very, very hard to kill in many circumstances where emotions are involved, especially if those emotions were particularly pleasurable or not.

Why does this have relevance?

Problems in application

Well, let’s take an example of an aversive counterconditioning programme I would never use myself but is used to cause conditioned aversion towards things. Say for instance your dog has been bitten by a venomous snake and you want your dog to find snakes so aversive they don’t chase them and try to bite them. You might pair up the snake and follow it with a shock. Likewise, you could do the same with chickens or cats or whatever. Chickens = shock. Cats = shock.

The first thing is that the unconditioned stimulus (shock, in this case) needs to be so powerful that it will outweigh the positives of chasing things. I know dogs hit by cars who enjoy chasing cars that much that they’d run through the pain of it. I know dogs who’ve arrived in the shelter with three shock collars on. I’ve worked with dogs who found biting so pleasurable as part of bite sports that the handlers had used two shock collars AND a prong collar…. it’s pretty hard to know how aversive something would have to be for it to outweigh the positives.

The second thing is that I’d argue the brain is learning exceptions. Oh, not that one? So every time you have a gap in your training, you’re going to have to know that the behaviour will likely come back again. Thus, you may think that your dog now finds snakes aversive, but after a delay, that pleasure can come back again. Likewise if you change the context. Also likewise if they find the snake again without the shock.

Obviously, this works the other way around. I may be using food or safety with a dog who is fearful of humans. I shouldn’t be surprised that I may feel like I’ve made loads of progress one session, but then the next, the emotional response is right back up there. Or, we go to a different venue and – boom! – fearfulness all over again. Or, we hadn’t really got to the true problem, such as the dog not liking people moving towards him with their hands out, and we might have done loads of work with people moving towards the dog, or standing, or putting their hands out, but none with all of them, only to then find we’d never really, truly, addressed the problem in the first place.

So respondent conditioning is surprisingly durable and treatments notoriously open to failure unless you know the pitfalls.

What is respondent counterconditioning?

So what is respondent counterconditioning then, and how do we use it with dogs?

At its most simple, it’s just pairing up bad stuff with good stuff.

Scary person appears > predicts the arrival of yummy food.

Scary dog barks > predicts the arrival of yummy food.

Scary vet visit > predicts the arrival of yummy food.

Unpleasant car journey > predicts a great walk afterwards

Scary person appears > predicts a great game.

That’s all there is to it. Pair up the bad stuff with the good.

It doesn’t involve clickers, reinforcement, marker words or anything more complicated than bad stuff > good stuff. That’s all.

Some people believe this causes an incompatible emotional response. In other words, play is incompatible with fearfulness. Eating is physiologically incompatible with fight-or-flight responses. Other research suggests that during counterconditioning activities, the neural pathway which stores the memory in the first place is re-opened and re-laid, a process called reconsolidation. In other words, when we remember stuff or relive stuff, we’re actually in the process of rewriting our memories about it. For instance, my brother reminded me of an event some years ago and I struggled to recall the details of it. Later, as we recalled the events, we were actively in the business of making those neural circuits work again and this reconsolidation is actually when the neural circuits are weak and open to being laid in a slightly different way. Imagine, if you will, a piece of countryside with a train track laid across it. Imagine that in the process of the train going across it, shortly after, the track itself becomes easy to relay, so that you can push it ten metres to the left, add a kink or a bend, even, gradually, relay it completely. When the track hasn’t been in use, it’s just fixed and solid, needing a team of twenty to come in, remove it and relay it. When the track has just been used, it’s malleable and plastic. Normally, under normal circumstances, the more that train runs over the track, the more fixed it becomes in position. This is why, when I changed the password to this site, I accidentally chose a new password with the same starting letter, and even though my brain was saying ‘WRITE THE NEW ONE!’, because that first little letter cued me to write the old one, my fingers followed the pathway of the old password. Things become fixed the more we use them. The more we remember something, the easier it gets to do it. Likewise with memories. Those often recalled become more fixed the more we remember them. What the science of reconsolidation suggests is that just after we’ve remembered it, there’s a short window where we can mess with the circuitry. These techniques are used frequently in treating PTSD and also phobic responses to situations.

Consolidation and reconsolidation of learning

Now we can’t ask dogs to recall a time they felt afraid when a big scary teenager appeared on a scooter. We can, however, put them back in a situation where there are teenagers on scooters. As they relive the experience slightly differently, it makes that neural circuit malleable and plastic for a short time, allowing us to change how they feel. With humans, this alters how they felt about the initial event. We can’t know that this is the same for animals, although lots of work on the reconsolidation of fears in animals has been done and would suggest that the same thing is true.

So whether it’s the reconstruction of memories or whether it’s simply an incompatible emotional response, something is going on during this process that affects how we feel in the moment.

Years ago, I had a pretty bad car crash where I was shunted into a junction by a lorry who crashed in the back of me on the way to work. For a good few months, I was having panic attacks when driving, and my panic was starting to generalise to other roads and other times. I started a course of medication, and like all good behavioural medication, it also needs a concurrent modification programme. I worked with a psychiatric nurse and we almost did exactly this process… remembering the event and reconstructing it, remembering the journey and pairing it up with positive feelings of safety and control. We were, neuroscience might suggest, rewriting the memory itself. What that body of work might suggest is that animals also do the same. We aren’t unlearning… We are reconsolidating.

Before we even start to think about respondent counterconditioning, we need to bear these things in mind.

It’s not just SCARY STUFF > GOOD STUFF.

Contingency and contiguity

First, the good stuff has to be contingent on the scary stuff. In other words, the dog has to be aware that the good stuff IS ONLY happening BECAUSE OF the bad stuff.

Second, the good stuff has to be linked in a timely manner to the bad stuff. It should lag slightly behind the bad stuff, overlapping or having a tiny gap of less than seconds. Let’s not get into the fact that Mary Cover Jones’s experiment with the boy and the rabbit actually was backwards conditioning…. that’s a whole enormous contrary bag of unpredictable science to wrestle with… let’s keep it simple and say that it’s very useful indeed if the bad stuff is followed almost immediately by the good stuff.

Contingent and contiguous.

Third, the good stuff has to be exceptionally good stuff. It has to be more powerful than the feelings elicited by the bad stuff.

Improving your respondent counterconditioning

There are two ways you can really help this. The first is ridiculously clean set-ups and staging. Why do I find remarkable success with respondent counterconditioning when other trainers have already tried it? Because I manipulate the situation so that it is incredibly clear to the dog that BAD STUFF > GOOD STUFF. There is a very, very clear connection for the dog between the two things. Nothing else is going on. It’s not sloppy. I’ve not got hundreds of competing variables. My sessions are constructed so that the training is so flipping obvious to the dog that they get what’s going on in a couple of trials.

Here are two posts to help you with that:

I want no other distractions. Just the bad stuff and the good stuff.

I have exceptionally good quality good stuff. Paté usually. Black pudding. Tripe. Stinky, yummy, amazing good stuff that I know is the highlight of the dog’s life. Lidy doesn’t like crunchy stuff. She likes easy to swallow yummy stuff. Heston prefers meat to cheese. You’ve got to know this stuff. Don’t, please, start with carrots, even if you could.

Also, keep the sessions short. Respondent processes aren’t hours long. We get in. We do 6-7 trials. We leave. We finish on a win. I want the whiplash head turn within a couple of trials, so I’ve got to know where and how the dog reacts, and work under that threshold.

I’ve got to have a good understanding of threshold. Camhi (1984) points out that reflexes are a gradient response and action patterns are an ‘all-or-nothing’ thing. That’s to say that if my dog starts salivating when I get their bowl out, they’re not at 100% salivation mode straight away. It takes time to amp up to full drool. If there’s pepper spray in the air, you might feel your nose being a little itchy as the pepper intensifies or as you walk further towards the source, only then to do your sneeze. Action patterns, on the other hand, are all or nothing. We don’t know enough about how to divide these seamlessly into two piles, but it suggests that if you’re working on predatory behaviour, if you’ve triggered it, you’re in the full thing. You can’t be a little bit chasey. We don’t know enough where emotional responses sit to know if they’re ‘all or nothing’, but a rough survey of my colleagues who deal with separation-related behaviours suggests that might well be ‘all or nothing’ – it doesn’t kind of build up as time goes on. Your dog isn’t a little bit panicked. This is important because we might feel like we’ve been changing our dog’s emotional response to stuff when in fact, they just weren’t triggered before. We need a good understanding of how thresholds work.

We also have to have a good understanding of when to switch to operant mechanisms – something I’ll share with you next week. Knowing the moment to switch is crucial.

Other posts about respondent methods

I’ve written extensively about improving your respondent counterconditioning techniques because I’m often dealing with emotional dogs or predatory dogs. It’s important to know:

How to set up training scenarios cleanly

How to use a stimulus gradient

How to work under threshold

When to use desensitisation (a form of respondent counterconditioning, where the unconditioned stimulus is calmness or safety) and when to use respondent counterconditioning. They are not the same thing. I need desensitising to the number of times trainers are implementing a stimulus gradient and thinking it’s desensitisation. It’s not. Desensitisation is particularly useful when your dog is sensitised to particular triggers that you need them to ignore. I use it most often with predation but it has its uses with fears too.

How to use a conditioned safety cue with fearful behaviours.

You also have to have a good understanding of what ‘good stuff’ means to your dog. That’s very much up to your dog. I use food because it’s convenient and it also works on the autonomic nervous system where play doesn’t. Play can also increase arousal and sometimes I don’t want that. Food can too. That’s another reason I need to know the dog I’m working with. Keep sessions short, clean, clinical and efficient with a carefully constructed stimulus gradient and a pairing that is so obvious to the dog that it gets their attention. Repeat often. Repetition in different contexts is how you get over the challenges of spontaneous recovery, renewal and reinstatement. You’re not unlearning. You are reconsolidating. Yes, there will be set-backs, but you are never back at square one. There are days when behaviour that I thought to be long dead comes back and I’m all Really? Really? This? Now??! But why??!

When to use respondent counterconditioning

Another thing we’ve still much more to learn about is WHEN respondent counterconditioning should happen in relation to the original event and then any recovery, renewal or reinstatement. What we know is that those memories have a short window in which they can be reconsolidated differently.

Lidy gave me an excellent example a few months back. She’s never been much of a car or bike chaser, thankfully. Plenty of malinois who can’t resist the lure of the wheels, along with their herding brethren. Given her predatory and aggressive behaviour, this is somewhat astonishing to me. However, we were caught out by a rogue cyclist who whipped past us on a pathway in the forest and she lunged at him.

What did I do?

Well, we had a thirty minute break and we drove to a place I knew I’d see cyclists in ordered and neat distance. We drove to a popular lakeside walk and we watched cyclists from the car. We ate snacks contingent on the cyclists and we did so for a brief ten minutes. We saw six cyclists. We ate six bits of chicken. Then we went home. Yes, it took us an hour to get there and back… the set-up is so important. It was worth it.

When she had a reaction to a lorry that drove past too close and too fast (and, I have to say, nearly headbutted the stupid thing and surely would have sustained some terrible injuries) we did the same thing… we went and we watched cars for ten minutes in very controlled circumstances. We ate sausage. We went home.

Not only that, we then had a sleep on it (guardians need respondent counterconditioning too) and then before we went out into the real world the next time, mindful of the knowledge we have about spontaneous recovery of behaviour after a time lapse, we went and we did the same thing we’d done the day before in a different place. We watched the cyclists. We watched the cars. She got chicken or sausage. We then went on our walks. I’m not taking a dog right back into the world the next day without a carefully-constructed trial first.

Be mindful of the bounce-back. Be mindful of what memories you want your dog to lay down from one session to the next. Be mindful that sessions should be controlled and sharp.

Working with multiple triggers

One thing people often ask me when they have a dog with multiple triggers is which do you countercondition first. Actually, what you want is a dog who is savvy to the process, as mine are. You also want to start with the trigger or stimulus you can control the most cleanly and to which your dog has the least response. If I have a dog who is fearful of multiple things, I’d also be thinking about a chat with the vet about behavioural medication to run alongside the programme. But if I had to choose between the stuff Lidy is afraid of – people and dogs, on the whole – I’m taking people first. People are way more predictable than dogs. I can co-opt them into the process as a stooge. Quite often, I ask my clients who are doing respondent stuff with their dogs to be the stooge. Nothing makes you understand the needs of your dog better than watching the needs of another dog. But it depends. Her response to dogs on walks at the shelter was so pronounced that we started with people and dogs as a unit. At least people walking dogs on leads are predictable, not least in the shelter where they’d happily walk another way. I’m pretty aversive, I know. So you work on one thing. When you do it with the next, it’s easier. All the dog is learning is Oh, that works HERE too? With THIS?

In those conditions, I feel like we can really use respondent conditioning much more powerfully.

Troubleshooting

There’s a lot we’re still learning about what respondent counterconditioning actually is and how it works at a neural level. We’re still learning about the precise triggers that elicit responses from dogs. We’re still learning in real life because these are not often things studied in the lab or in applied scenarios. We’re also navigating the ethics and the fallout of such methods because no behaviour change protocol is without consequence. In any case, where clients have already tried it and it doesn’t seem to be working, I need to ask:

Is the unconditioned stimulus strong enough?

Is there a suitably gradual stimulus gradient in play?

Is the situation clean enough?

Is the set-up short enough?

Is the dog at the right point of finding the stimulus salient and noticeable, yet not responding to it?

Does the session finish positively and allow the dog to rest, play and sleep in order to ‘fix’ or consolidate these new memories?

In the case of multiple triggers for impulsivity, fearfulness, aggression or reactivity, has the guardian discussed the appropriate behavioural medication with a specialist who understands that fear and impulsivity may need treating differently?

Has the trainer or guardian picked off a trigger that does not cause too strong a reaction and that can easily be controlled?

Has the guardian or trainer practised in different contexts, remembering to lower the difficulty each time they begin again?

Has the guardian prepared the dog for the next session in a fresh, well-prepared, controlled environment?

Answering no to any of those questions shows me the area where I need to work.

Respondent counterconditioning is also helped by having an operant dog. But that is something I’ll leave for the next time!

Not got my book yet? Check it out on Amazon!