Global lockdowns, decreased road traffic and non-existent air traffic meant that for many of our dogs, March 2020 to June 2020 were peaceful times. I know for many anxious dogs, it was a break from the daily grind. It wasn’t a surprise then to find my books filling up with anxious dogs post-lockdown. It seems strange now to think back to those times without traffic and planes disturbing the peace.

For anxious dogs who returned to normality post-lockdown, it seems to have hit them really hard. The only equivalents I can really give are where you give something up and then find you can’t cope with the levels of whatever you used to do.

For example, I gave up drinking alcohol little by little over the last fifteen years or so. It wasn’t planned. It wasn’t something I purposely quit. I just started drinking less. Now, half a glass of wine makes me sick, beer bloats me in ways I don’t want to describe to you and even half a glass of cider makes me hugely inappropriate.

It’s the same with many things I’ve quit the habit of in the last few years. I used to always wear perfume. Five or six squirts every day. Wrists, neck, clothes. I had so many different bottles and I was never without. Now, I can’t even tolerate the slightest spritz – it seems to follow me all day and give me a headache.

And don’t get me started on traffic and city life!

Like the proverbial frogs in hot water, we habituate to noise, smells, experiences, tastes and even our daily activities. Take us out of the water for a while and we find it impossible to tolerate when we’re immersed once more.

And I think this is what happened for a good number of dogs. Add more regular walks, anxious guardians, families off work, changing routines, people at home more and a beautiful spring, and it’s not a surprise to me that our dogs found it difficult to tolerate what they’d previously habituated to in the past. For our anxious dogs, I think this was particularly marked.

In the past few months or so, there’s definitely been something in the air about the use of predictable routines and objects in dogs’ lives. First, it was a little-shared study in by Joke Monteny and Cristel Moons in Animals back in January: A Treatment Plan for Dogs (Canis familiaris) That Show Impaired Social Functioning towards Their Owners.

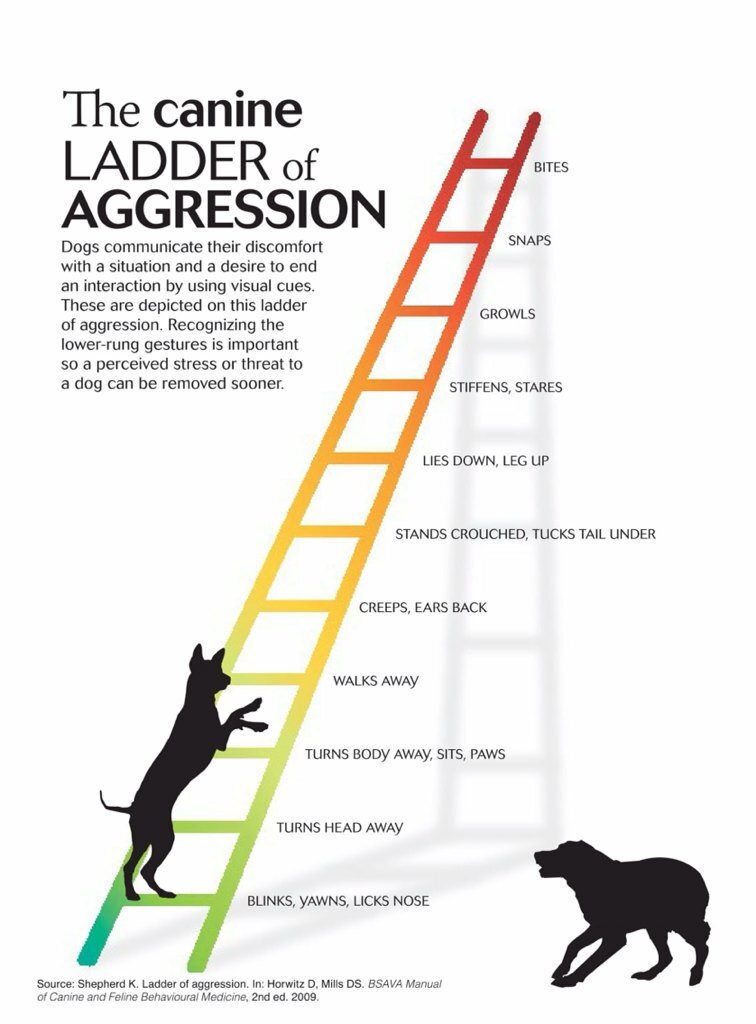

The paper is very nice, discussing the effects of modifying the environment and lowering stress in dogs who are reactive to their guardian’s behaviour. I read it nodding sagely at the parts that informed guardians about thresholds and low level behaviours. They used Dr Kendal Shepherd’s excellent Ladder of Aggression that I shared a couple of posts ago:

So far, very straightforward. Recognise the lower level stress signals and notice how your dog is feeling. That’s always my starting point with anxious dogs.

Then they suggest education, and explanation, giving reasons for the dog’s behaviour, explaining things from the dog’s point of view. Yes, yes. Always good. The paper’s authors suggest going back through the guardian’s behaviours to explain to clients what the dog is doing at each point, and the effect of their behaviour on the dog.

They go to explain how to manage the environment and avoid stress, as well as avoiding punishment.

Finally, just when I was thinking they’re simply describing a very simple procedure, some 2500 words in, they hit me with two descriptions. One is something they call The Predictability Game. The second is something they call a safety cue.

The predictability games are great. They tie in to lots of other things I do with the guardians of anxious dogs, from Leslie McDevitt’s Pattern Games to Chirag Patel’s Counting Game. As Leslie McDevitt often says, they teach the dog rules and predictable patterns. It doesn’t matter what is going on in the world around us, the dog and I are involved in a relationship, we’re doing stuff. We’ve got our routine. We’re undertaking easy, fun, reliable, predictable, reinforcing activities that normalise the unpredictable and help dogs cope. I’ve been doing a few of these with a couple of clients, and one said to me this morning that their dog has become more affectionate and more relaxed as a result. The dog knows the routine. It brings safety. The dog isn’t spending all day scanning the environment for threat and they trust their human to keep them safe. For me, I’ve used these hugely with Lidy – she comes out like Kato in a Pink Panther movie, attacking everything on site. Pattern Games are our crutch for when the world gets tough. We go back to our really simple ‘one – two – three – drop’ food game. We play ‘ping pong’ where she shuttles back and forward for treats. I use these to vary the pace and to bring down her energy levels and to provide a reliable routine. I also love them because they’re moving games. So many trainers ask dogs for stillness when threats are approaching, especially when the dog is on the leash, and it’s just creating a lot of problems because the dog has nothing else to do. So they go back to relying on predictable behaviours like barking that get them what they need – safety.

That tied in to listening to Leslie on Hannah Branigan’s great Drinking from the Toilet podcast, where again, they were talking about predictability and routine. I highly recommend this episode if you haven’t already listened to it. I’m on my fifth time through and still it’s giving me more. You can find the podcast here.

I’ve also used Chirag Patel’s Counting Game for the same kind of purpose. To be honest, I don’t think it matters what you do with your dog as long as the dog enjoys it, it’s not adding to their cognitive load by being too difficult and it’s getting the nose down and breaking up the dog’s visual scanning of the environment. When I say “one – two – three” my dogs are back with me, no matter what, because what I’m about to ask will be easy and it will be routines we’ve practised a thousand times in a very large number of situations.

I find that this just builds up so neatly to Leslie’s ‘up-down’ game and to ‘ping pong’.

So the Monteny and Moon study really reassured me that this was a useful kind of approach to take.

But it got better. These safety cues. I mean, this was something I had to go away and sleep on, then come back and get my head into again.

So for Monteny and Moon, a safety cue is “a novel item for the dog without any previous association”. They give the example of a mat, and I think that is genius for a number of reasons, not least because it’s portable and you’ll be able to work with it in a variety of places. The process they explain involves working to create an association between positive experiences/lack of stress and the mat. So you’d start in a quiet environment where you are still and the dog is calm, where you’re not likely to be disrupted by television noise, music, doorbells, people arriving or other dogs. And you just sit whilst the dog does something fun. So you might give them a chew or a lickimat and just let them get on with it. If your dog is fearful around you, you do absolutely nothing other than give them a cue to announce the arrival of the mat, like “here’s your mat!” and give them a toy, puzzle, chew or food game and go and sit down. You do absolutely nothing. You don’t make sudden movements, you don’t play noisy games on your phone. You just sit.

This happens over a few times (and I’d vary the games/chews/puzzles so that the mat is the announcer of good stuff, not the toy or chew or whatever) and you need to do five trials where you can see the dog relaxes within five minutes of the mat going down.

Then the mat gets picked up and put away until next time. What you want is a positive association with the mat, so that just like Linus in Peanuts it comes to signify something pleasant and can induce a state of relaxation. To finish, throw a couple of treats away from the mat, say something like “mat time’s over!” and put the mat away.

If you use the mat often enough and gradually enough, it comes to help your systematic desensitisation. If you remember, that relaxed state is vital for desensitising a dog to things, so the “safety cue” is a way of inducing relaxation and calm.

Now I know objects can be a great talisman for dogs. For instance, for one very territorial dog I worked with, whoever had his bowl did not get barked at. If you arrive with a bowl, you are a welcome guest, whoever you are. It doesn’t make the dog feel better about YOU until later, but it does not evoke the kind of barking and aggression they were getting without it. Same thing in shelters for people who arrive with leashes or other recognisable “goodies”. It can also work the other way too. You may remember my saying about my dog Amigo who had quite clearly been trained with a fly swatter. Seeing him trembling to see one on a table told me all I needed to know. So these kind of items with a positive or negative association can induce emotional states such as relaxation (and fear, unfortunately, if they aren’t used correctly).

So I chewed this study over for weeks as its implications sank in.

When Hannah mentioned “certainty anchors” very briefly on her podcast, though, it sent me on a bit of a search to find out what she meant.

So a certainty anchor is exactly this: a learned process in which we use predictable factors as a crutch to cope with the unpredictable. Not unlike Monteny and Moon’s ‘safety cues’. Now in another life, I was involved in change leadership and working with organisations involved in a change agenda. Sometimes, we call this the Red Queen hypothesis, that we’ve got to always keep moving just to keep up. A kind of use-it-or-lose-it mantra. What I learned from my 4 years in consultancy was that some people find it hard to change.

We started with a really simple game – one I still play in group classes. The presenter pairs you up and asks you to stand back to back. You then have 30 seconds to make 5 changes. Then you turn back and your partner has to work out what you changed. The first time, invariably, people take things off. Sweaters, earrings, bracelets, watches, glasses. It’s fairly liberating. That kind of change I think we can all deal with – removing the extraneous. Nobody, by the way, ever removes the essentials. Interesting. I’m sure there’s something profound in that.

Then, without prior warning, the presenter tells you to turn your backs again and change 5 more things. Now people start to use the environment to pick things up. They pick up cups, binders, stand on chairs, put pens in their hair. I think generally speaking people do that too – abandon the extraneous and then add on new things.

Finally, once more without warning, the presenter asks you to do it again. Now this is where it gets fun. People get creative. People are liberated. I’ve seen shirts come off, or shoes. I’ve seen people make impromptu hats out of bags. I’ve seen them fashion earrings from pens.

But two things also happen. As soon as the presenter tells you the game is over, invariably, people change back everything to how it was. That says a lot about habit. And the second things is that people usually have a few things they’d never do. Like remove a wedding ring or change the finger they’re wearing it on. We don’t change our core values.

So all this is interesting, but out of four years’ work, if you ask me what I learned is that adults will invariably groan and shut down any time any change is proposed, even if it removes work from them. I also know they go back to default as soon as the pressure is off unless the change was wanted and it came from within. Change is hard, even for humans who seem to be one of Nature’s most adaptable species.

Change, at a biological level, is threat. Mice and rats who’ve been habituated to a new environment for five days are more likely to survive when a predator is then introduced, compared to mice and rats in a novel environment. Novelty is not good, especially when we’re under threat.

So this is where certainty anchors or safety cues come in. Author Jonathan Fields in his book Uncertainty says rituals help ground us. They help us find equilibrium. He says they’re powerful as tools in ways to help us deal with uncertainty and anxiety. It adds something known and reliable to your life at times of change. Their consistency is the crucial element – that we can deal with the cognitive load of change without it throwing us off balance. They’re a bedrock or foundation that allow our brain time to process the other things. Fields says these ‘anchors’ secure us and help us cope during times of stress and change. He also says that when we have these, we are then able to take risks. They give us some control over the uncontrollable. They build structure and build practices that allow us to cope in constantly changing circumstances.

Now for anxious dogs, we know that predictability and certainty help them cope. Routine, ritual and predictable patterns help them cope with the uncertainty of everyday life. They free up brain bandwidth.

Chirag Patel’s latest Domesticated Manners presentation makes good use of those anchors… the items in a dog’s life like bowls or blankets. I highly recommend everyone watches the whole video. If you’re just a beginner, it’s easy to follow, but for those of us who like the subtleties, there’s so much going on underneath the hood there that I watched that at least twice too.

Now a lot of these things are about props. Leslie McDevitt’s Pattern Games are about routines. For dogs who are anxious, I’d argue that both of these things are essential. But I think there is one more element.

Ourselves.

More precisely, our relationship and interactions with our dogs.

Now most of you will know my journey with Miss Lidy, my reprobate shepherd. About four years ago, I made her a promise. I promised that I would keep her life predictable. That I would be predictable. I didn’t say I’d become her certainty anchor, because I didn’t know such words then. I didn’t say I was her safety cue for the same reason. But I wanted her to know that when she was with me, none of the scary stuff would happen. Her voice would be heard and respected. She’d no longer have to rely on her teeth. I would be her routine and her regularity. I would always be 100% reliable. Our relationship would be based on consistency and safety.

Much of her first ten months here with me has been about the small routines of an ordinary life. It’s been about restoring predictability. It’s been about creating routines that we both abide by that help us both cope when the unpredictable happens. Sometimes, unpredictable things happen, but I’d like to hope that she knows that as long as she is with me, I am her certainty anchor and that I can generate for her those feelings of safety and security. If you’re well-versed in attachment theory, no doubt you’re reading this thinking about how we can be a secure base for our dogs, and I think that is exactly what I try to provide for her.

If we have anxious dogs, creating routine, regularity and structure can help us for those times of change. They help us cope. They may well be crutches, but nobody said the only way to live is to be completely self-reliant.

So what can we do to help foster a sense of predictability and build that foundation onto which change can be built?

First is to think about our daily patterns. That means regular times and sometimes even regular walks. That means being routine and teaching dogs patterns to cope when things change. I’m heavily reliant and massively indebted to Leslie McDevitt on that score, but I also use a lot of Deb Jones’s focus games from Fenzi Dog Sports Academy for exactly the same purpose.

Second is to teach a safety cue. Work on building up an association with a mat or an item like a toy. I do a lot of freework as well with anxious dogs, and having reliable, known toys and surfaces in there can also help dogs have an environmental base to explore the novel items in the activity.

Third, and perhaps most crucially for me, is to build up your relationship so that it becomes the safety cue, the certainty anchor. I’m sure you have friends or family members who act in that role for you – 100% reliable, you know you can trust them instinctively and completely. When you have that, you realise that you’ll always have that solidity from which to explore, to experiment, to try out the new. Of course, we need to make sure we’re fostering independence too – Lidy panics if she can’t find me in the garden once she’s spent her time exploring – and that’s something I’m conscious of too. All that remains to say about that is to make sure that we have a solid range of certainty anchors, including ones from within. Some of what we can do with anxious dogs is certainly help them know how to cope on their own and find their own anchors. Sadly, when I see ritualised or compulsive behaviours, I often see dogs who are using those in order to cope. Finding pleasurable, functional and productive behaviours that help dogs cope is part and parcel of overcoming anxiety.