One of the reasons many people come to Woof Like To Meet is to read about my disasterous experience with an adoption that inadvertently brought me, three years later, to a point where I not only – finally – understand it, but can work with dogs to help them overcome their emotions and deal with their triggers.

Dogs, much like toddlers and teenagers, have emotional brains. Their emotions are often sudden and intense, primitive and uncontrolled. Where we might be able to swallow our bile when we see a politician we don’t like on television, a dog is less likely to be able to control its urge to get up close and personal with an offensive act of aggression. Where we might be able to control our happiness upon seeing our friends, and where we are bound by social convention that makes it unacceptable to hump our friends if we feel anxious or jump all over them if we’re glad to see them, dogs don’t always have that level of control. That’s even though it can be just as socially unacceptable among dogs to hump or jump. A trip to the dentist may be a real fear for us, but a trip to the vet can be the Sum of All Fears to a dog. Without an intensely reflective neo-cortex override to remind them of things like manners, necessity and restraint, it can be harder for them to manage their emotions than it is for us.

Don’t get me wrong. Dogs do great at sorting it out one way or another. Few dogs end up biting and dogs who live in homes with rules know that humping, bouncing and jumping are not appropriate ways to greet people or other dogs. Sadly, more dogs bite groomers and vet staff, or find these experiences to be ones filled with horror and trauma for mildly uncomfortable procedures, although more and more vets are aiming to make the experience a fear-free one for pets, For most dogs, they handle these things with an amazing self-control.

But for some dogs, they have a tougher time overriding their impulses. That can end in a burst of behaviours that can be alarming, upsetting or dangerous. Where a degree of reactivity is normal dog behaviour, when a reaction is disproportionate to the environmental threat, our dogs may need a bit of help getting past this.

Lidy, the dog in the photo above, handles stress very badly indeed. This post will largely explain the things we do with her to ensure that she is safe and the people and animals she comes into contact with are safe too. She is currently in our shelter, having been surrendered last year. Her behaviour in and around a number of things leaves a lot to be desired. She is a dog who has little impulse control: the firstlings of her heart are the firstlings of her mouth, to misquote Macbeth. In other words, she goes quickly from stimulus to reaction in a fraction of a second with no orange warning light in between. She is the Ferrari of reactions. In this post, I’ll look mostly at over-arousal, impulse control and aggressive behaviours rather than fearfulness, and pick up the thread in the next post for fearful trigger responses.

For dogs who are trigger-reactive (be that a fear response, an aggressive response or a defensive-aggressive response), they can exist in a happy state of equilibrium most of the time. For Lidy, in a stimulus-free world, she is a happy soul. For my reactive dog Heston on his walk this morning, he had no cause to react because there were zero things to set him off. These stimuli – whatever they may be – are also known as triggers. For dogs in a trigger-free world, they are in a happy place. No stimulus, no need for reaction. The purpose of their reaction in face of a stimulus is mostly to make the stimulus go away. In fearful dogs, they will seek to flee in order to make the stimulus go away. On the flip side of that, some dogs will make an awful lot of noise to make a stimulus disappear. And yes, they will attack if necessary. Or they’ll just make a lot of noise. Introducing two dogs to each other a couple of weeks ago, one of the dogs barked for twenty minutes every time the other dog came near. For any pet owner, I am sure that you want the best for your dog.

When we deal with reactive dogs, it’s important to remember one thing…

No dog is aggressive all of the time. And no dog is completely aggression-free all of the time. All dogs exist on a spectrum.

Aggression, excitement or fearfulness are just responses, reactions. They don’t exist in a vacuum. Knowing that your dog is reacting to in the environment is vital.

A dog who is reactive has just not yet learnt appropriate ways to deal with the world around them. It’s our job to help them learn. It’s our job too to understand their triggers and what stimuli affects them as best we can, whilst understanding there is a world of smell, hormones and sounds that we cannot hope to identify.

For Lidy, she has a number of triggers: exciting or emotional events, environmental energy levels, other dogs behind barriers at the shelter, cats behind barriers, free-roaming cats, pushchairs, wheelbarrows, wheelchairs, children, strange humans, people who walk too close to her and other dogs. Like many dogs, she finds other dogs’ behaviour to be both stimulating and contagious. But in a world where those stimuli don’t interfere with her existence, she’s not fussed by them. Being in a shelter is overstimulating for her and often means that excitement and lack of impulse control tip over into overt aggression. There are times when this is more overt and there are times it is more manageable.

For most people, they have scant knowledge that their dog is going to react. For them, it seems to come out of the blue. You’re walking along, someone’s walking towards you, and boom! That is Lidy all over. Forget all the ostensible warning signs you might expect – a freeze, a growl, a bark, a snarl, an airsnap. She goes from 0 to lunges, circling and snapping often in one fell swoop.

So has a dog like this got any hope at all?

In fact, she has made lots of progress. Actually, that’s only partly true. It’s me who’s made the progress in understanding her triggers. I manage to keep her in the learning zone for 80% of our time. Sadly, the rest is not easily under my control in a shelter environment. There is literally no way at all to avoid unexpected stimuli when you are surrounded by dogs, cats, moving things and people.

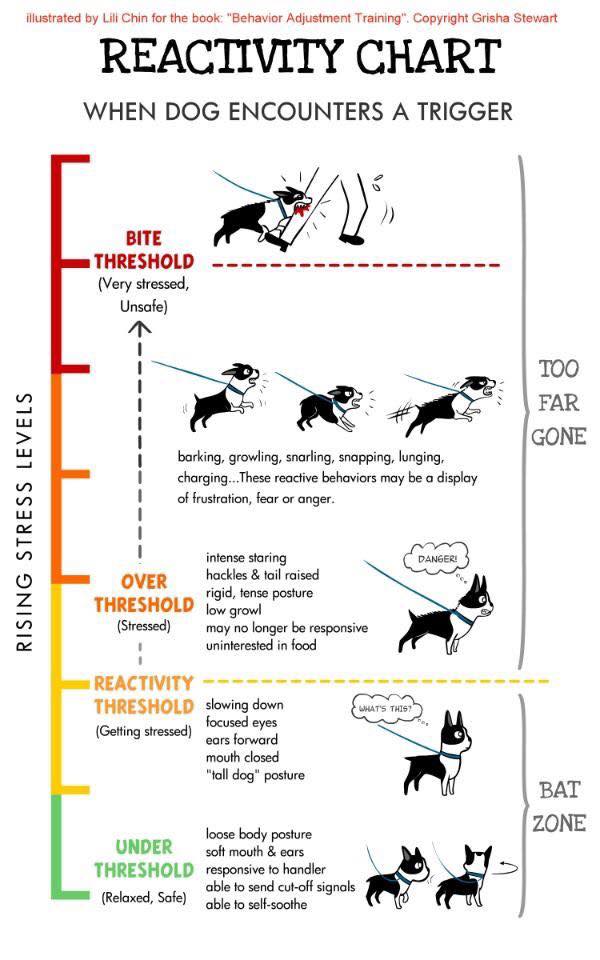

Keeping dogs’ in the learning zone is vital to help them overcome their behaviours. By the time most of us realise that our dog has tipped over, they are already reacting to the stimulus and they are no longer listening or learning. To help them learn a new response, the handler or owner must keep them below what is known as ‘the threshold’ – ie keep the dog in a state of relative relaxation where they haven’t been hijacked by their emotions.

Lili Chin & Grisha Stewart

Although Grisha Stewart picks up some of the more obvious clues that a dog is getting aroused, there are others you can explore too. Lidy, by the way, goes from 0 or 1 on this scale to 7 or 8 without very much time lapse if she is surprised by a stimulus. The more something startles her, the quicker her reaction. Knowing her triggers means I can keep her at 0 or 1 and help her begin to manage her reactions.

So how does an over-aroused or defensive-aggressive dog look when it encounters a trigger?

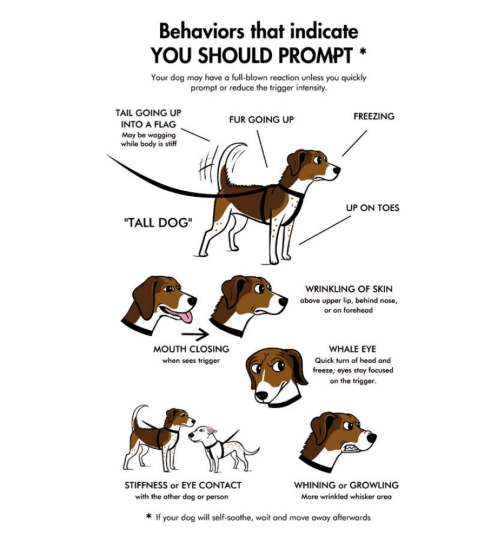

At first, they may stare or even avert their gaze. Their bodies will either stiffen and lean forward, or move away and turn away. Many reactive dogs will slow down to gain more information about the stimulus. You may see their nose squash up and wrinkle, their whisker bed get all lumpy. Mouths close. Their eyes open wider and fix hard. Some dogs stand their ground whilst they make a decision, staring dead on at the target. I noticed Fiesta, one of our other dogs doing this to Lidy when approaching us on a walk. Lidy was more interested by a mouse in the bushes, but I could tell trouble was ahead because of Fiesta’s confrontational posture. Hard, diagonally side-on, blocking the way, eyes hard, not moving, ears forward, mouth closed, tail high, leaning slightly into the lead. She had simply stopped dead.

All of this behaviour is communication. The desired recipient was not me, it was Lidy. It was a message that clearly communicated something. Now whether it said, “I know you, you ratbag. Behave yourself around me!” or whether it said, “My pathway!” or whether it said, “You steer clear of my handler!”, we’ll never know. But what it did say quite clearly was, “my intentions are hostile – don’t come any nearer”. Even I could see that.

Would I have been able to walk Lidy towards her when Lidy does exactly the same thing? Not on your Nelly. Not without the pair of them lunging at each other on the lead. Not a chance this was going to end peacefully unless the monkeys holding the leash took control. With a bit of negotiation from a distance, we went our separate ways with Lidy blithely unaware that she was about to cross a very hostile dog.

But what would have happened if I’d moved forward? For Lidy, she lunges until she is at the end of the leash, and then she jerks in a 45° arc trying to get away from the leash towards the target. When she can’t get to the target and the target hasn’t gone away, she generally keeps jerking at the leash, front legs off the floor, back legs low, springing in, staring. She doesn’t growl, snarl, bark or snap. If Lidy snaps, it’s because she is in range of something to bite. Her intention is very clear.

And what happens if they move in?

I have to have her on a shorter and shorter leash. She will then circle back to me and turn and jump up on me in frustration.

This happens too when there is no direct target in front of us, by the way. It can happen after all the stimuli are behind us. When all those triggers have stacked up, she can make it through to the home stretch before turning it back on me. Knowing her triggers is absolutely fundamental in avoiding an accident, but also in helping her overcome them and learn a better response.

Sadly, Lidy has a lot of triggers. Some are more important than others. Not lunging or charging other dogs is pretty important. It is absolutely vital when we walk that she is not practising this behaviour and that I am engaged in eradicating any situation in which she might feel the need to do so. Whilst I can’t avoid every trigger in the shelter, I know that the more she practises a behaviour, the more she will think that it is her behaviour keeping the stimulus away from her.

So… where do you start?

First, you start by knowing what your dog does at each of these points on the threshold. What does your dog look like in the milliseconds or seconds before they bark, growl, snap or lunge? This is where a friend with a video camera can really help you. Video your dog in a safe situation with the approach of a known stimulus. What does the dog do as it approaches? You need to video those moments from ‘innocuous, minding my own doggie business’ moments to ‘hey, there’s something over there!’ and a little beyond. Probably, you won’t need to get your dog to a point where they are shouting to the other dog: you’ll have seen that bit often enough.

What we are interested in are the behaviours before.

What do they do?

Generally, it’s pretty standard. They’ll notice the stimulus and turn towards it. They’ll stand still and stare. Their body may become stiff and rigid. Tails may go up. Ears may go forward or prick up. They may begin to lean into the pose. I often look at the mouth, as their mouths often close. Your dog will have personal clues – for Heston, it’s his tail and mouth. For Lidy, it’s her mouth alone. Heston’s doesn’t flag, like the illustration below, until he is much later into his reaction. A high tail means I have no chance of getting his attention back on me by calling him, but a low tail and a closed mouth mean I can usually get his attention.

If I get to wrinkling around the nose, whining or growling, it’s too far for Lidy. She rarely vocalises anyway. Heston does, but if he is at the whining and growling point, he is too far gone for me to get him back. In the photo below, he’s still deciding. Interested, but deciding.

If Heston’s tail is my cue for his over-arousal, Lidy’s ‘sit’ is. She will quite happily park her backside. It’s not a calming signal. It’s a rather clear, ‘I’m just waiting here until that thing gets close enough’. If I see her sit, I know it is absolutely time to move her away.

At this point, I’ve got a few choices of things I can do. I also need to have a few well-taught rock solid behaviours in advance.

The first is ‘Sit!’

My dog’s ‘Sit!’ has to be pretty rock solid. I should be able to ask for a sit and get it if the dog is under threshold. If the dog is too aroused or overstimulated, it’s a good gauge that I need both more teaching of a sit and less arousal. If your dog does not have a rock-solid sit, start at home or in the garden, in the park, on lead… everywhere. Many of the exercises are going to depend on a sit or a down, so it’s vital that your dog has mastered it. Sit is a great behaviour because it means your dog is not pulling towards or making lunges at other dogs.

I also like to encourage my dog to learn ‘Look at Me’, building up the length of time they can focus on me. Although this can be difficult for some dogs, you can make a lot of progress. Lidy doesn’t much do eye-contact, so I just want her to orient towards my face and focus on me. We’re working on eye-contact, but it’s tougher to get past two or three seconds at the moment, most especially when she is surrounded by things that make her react.

You can also teach other obedience behaviours alongside this. Down, High Five & Hold (where the dog gives both paws and sustains it) and sit-at-side can also be really helpful behaviours for a reactive dog. They break the behaviour and ask the dog to do something that is incompatible with looking at or orienting towards the other dog. Sitting and lying down are also calming signals for dogs, so for any dog who is approaching, it gives the impression that your reactive dog is calm. This can be a really important factor as to whether your dog chooses to react or not. I’ve seen Lidy literally going ape at a barking out-of-control dog as well as size up to a shih tzu who turned away and stopped Lidy in her tracks. For Hagrid, a shepherd I walk regularly who is very aggressive towards other dogs, he walked past a dog getting a tummy tickle (because lying on their backs is a diffusing submissive posture) when he had been pulling at the end of the leash and airsnapping at the same dog who’d sized up to him. Don’t overlook the body language of the target dog or person.

I have also thrown a handful of treats on the ground if other dogs approach by surprise. It doesn’t always work with Lidy, but it mostly works with Hagrid (and never works with Heston who is not food-orientated on the whole) This makes your dog sniff the ground, another diffusing behaviour. I work on this alongside ‘Drop!’ and as soon as the dogs hear the word, they are expecting treats on the floor, so they start sniffing the ground, an excellent diffuser of tension.

Another way that you can also avoid your dog giving off hostile vibes to an approaching dog is to use a squeaky toy to attract your dog’s attention. Where treats on the floor don’t work with Heston, he goes all playful and floppy when he hears that sound. For Lidy when she is lost in tracking a moving cat, a squeak is a great disrupter. Not only in Heston’s case does it disrupt their focus, but it also means you can keep it on you as you hold the toy. When your dog appears playful and relaxed, approaching dogs will be relaxed too. Whilst Hagrid may be happy to let dogs past if they are polite and non-vocal, letting any number of big, over-excited dogs go past, his focus is broken by barking dogs coming his way, as you’d probably expect. But sitting, lying down or getting playful are good signs for your dog to give to other dogs.

Teaching your dog to touch your hand is also a useful skill. A dog who can touch the owner’s hand when asked can be directed away from looking at the stimulus. It’s not so easy to look at an approaching child in a pushchair if you have a hand in front of your face directing you away.

The next is loose-leash walking and a “Let’s go!”. Being able to make a U-turn with your reactive dog is the best way to be able to put some space between you and the thing that’s setting them off.

There are lots of other things you can also do to help your dog build up a better listening relationship with you on a walk or out in public.

Emily Larlham’s Attention Games are really good for this.

Leslie McDevitt’s Pattern Games are perfect for this. A smooth U-turn/sit can also help. Leslie’s ‘Up/Down’ game and the ‘Engage/Disengage’ game can also help alongside the ‘Look at that!’ game. I’ve been playing this with Lidy to get her to look at and not react to dogs in the distance. She can manage about 10m for a 2 minute presence around non-reactive dogs. Once we’re past dogs, we’ll be on to people and pushchairs, wheelchairs and buggies, before trying it finally with cats.

All of these things are things I practise at first in a safe space where I get really good focus from her. The more I do it, the more she trusts me and the more habituated she is to the fact that when I ask her something, more times than not, there’s something in it for her. Two months in, and I don’t reward every sit – sometimes I give her a jackpot for a sit, or I’ll reward the most difficult ones she does.

How do these things help you when you’re faced with a reactive dog?

The first thing to do is assess whether the stimuli is something you can control, or is moving in slowly enough that you can practise the other things.

Sometimes, it’s just too difficult and you know that your dog is going to fail.

In this case, escape and evade are my best tactics. If the person/dog/cat in the distance is moving in, I need to put more distance between us first before I can ask for the other stuff. At this point, I need to have taught the “let’s go!” cue when my dog is good and relaxed. People, dogs and cats are unpredictable things. Even if I have shouted a warning for people to stay outside Lidy’s 10m radius (for their own safety!) people still come too close. They sometimes tell me she is a sweet dog before seeing her jump ‘out of the blue’ (which never is, to me) and sometimes make contact with them. What makes me most angry with some people is that they know she does this and yet they still insist on moving in, even if I am yelling at them to stop so I can get away. Unless they are people I have deliberately asked to be involved in her training, I tend to treat others approaching as a situation she can’t yet handle. I’d rather back up than let her practise poor behaviours.

It’s really simple. I don’t pull or get tense. I react way before she sees the target. I say, “let’s go” or “Allez!” and turn in the other direction at a fairly brisk pace. Though you may find from time to time that your dog looks back, keeping them moving away helps them get what they want: space.

If I’m totally not in control of the situation about to present itself, I will do nothing other than walk away. With a reactive dog, you have to pick your battles.

If I can put sufficient space between us so that both go back to “mouth open, loose body, checking out the environment” and she is no longer fixed on the thing approaching us, and I know I have a bit of time to work, I’ll use it as a learning opportunity.

This is where I’m going to pick up on my pre-teaching. I’ll sometimes ask for a sit and then play “Look at that!” ten or so times as the stimulus approaches. This works doubly well if high-quality treats only come out when the triggers are about. If Lidy realises that other dogs = treat time, it’s helping counter-condition her response as well as teaching her a new one. I’m also going to put into practice other pattern games we’ve been playing so that Lidy gets used to the fact that every time there are other dogs about, we have our routines. This is exactly what I did with Hagrid to the point of he is always ready to focus on me and to work with me.

From here, it’s easy to slip into Behaviour Adjustment Training, where you use stooge people, stooge dogs, stooge pushchairs, stooge cars and even stooge cats. Grisha Stewart’s excellent programme works with your dog under threshold to help them learn better behaviours around their triggers. In the past, a dog’s behaviours have caused them to think magically – to make a connection between what they did, like barking – and an outcome, like a person moving away. Behaviour adjustment training is about working with your dog and understanding your dog as well as teaching them new behaviours around a trigger. This is why it’s my absolute go-to favourite for reactive dogs. It is so simple, so easy to follow and so effective. Sure, it takes time. There are no miracle cures with dogs if you want the learning to come from within. Sure, you can ‘impose’ learning through managing the environment or even punishing a dog for their reaction until it stops, but it is ineffective in terms of helping a dog make sense of the world by itself and make good decisions. Here, they learn gradually that the cause of their reactivity is nothing to be over-aroused over, fearful of, or aggressive towards, by keeping them always in a learning zone and controlling the environment so that the dog realises their previous behaviour is ineffective.

There are other methods you can also use, such as Constructional Aggression Treatment, which involves a dog learning that when they are calm, they get what they want. Here, through controlled environments, the dog learns that their stimulus or trigger goes away when they are calm. Why I prefer BAT when you’re working with dog-reactive dogs is that it is kinder on the dogs who are being used as a stooge dog. To expect a stooge dog to remain calm in the face of aggressive displays is too much for me. Often, dogs actually worsen their displays as another dog turns and walks off (and the same for a human too) so this technique involves the stooge dog having to stand and wait until the reactive dog realises its behaviour is not causing the other dog to leave. Whereas Grisha’s methods can easily be accomplished by an interested person who understands a bit about dog body language (like me), Constructional Aggression Treatment should only be done with a trained professional.

So with air-snappy dog-reactive Hagrid who would lunge and snap at any dog who passed, he can now offer a sit, a down, a look at me. We’re working up to walking past calm dogs who are displaying peaceful behaviours. The reality is for Hagrid that he may never cope with a young male dog lunging and yapping less than two metres away from him, but he finds it much less traumatic to walk on our high-traffic walking routes around the shelter.

With leapy Lidy and her over-zealous mali mouth, who is physically easier to restrain than Hagrid, weighing in at half his size, she is still learning. People are more likely to take risks around her even though she is more explosive, just because she is smaller. Because of this, she gets more frustrated. We’ve not yet mastered human beings walking past yet. Dogs and cats are a bit of a way off. But today she successfully navigated a cat walking across the courtyard, one asleep under a bush, one peering at her from under a trailer, one running into the cattery. Two weeks ago, she would no doubt have turned and jumped on me. She could still yet. But we’re making progress every day. So she lunged at Gilda and let Kayser pass without reaction at around 15 metres distance. The best bit is that there is much less redirected energy and over-arousal. She may never be able to master the multiple triggers the shelter throws her way, but where she is not surrounded by things that overwhelm her, she is a most marvellous dog. She will never be able to walk through a crowd of people at a market. She will never be able to sit and watch a cat saunter past. But as long as her future owners understand that she will probably always be an on-leash kind of girl, there’s no reason she wouldn’t make a loving house guest. There will always be considerations in situations she finds overwhelming: greetings, crowds, moving people, excitement, energy, dogs and small furries, but were she to live in a home like mine as an only dog, I think she would make amazing progress.

And for my handsome, shouty Heston? He whined a little in the vets. Once or twice he pulled towards a playful bichon on heat. He even smelt a lady’s hand. He coped with a dalmatian who arrived and bundled in through the doorway less than a metre away, and he deals with my ever-changing houseguests with much less stress. His final challenge are visitors: this place is very much HIS. I don’t get enough visitors to work with him on it, but to tell the truth, it’s always handy to have a dog who is suspicious of strangers and who makes a fair bit of noise. His bodyguarding isn’t always merited, and he is quicker to turn off the offensive barking, especially when asked. His dog-dog reactive days are restricted to dogs behind fences or dogs alarm barking in the distance, perhaps the occasional sneak-up dog who takes him by surprise when we’re out on a walk. His human-reactive days are restricted to guests in the home and a rather persistent power walker who likes to wear a full ski suit in June. I kid you not. I’ve told Heston I find that pretty freaky, and he agrees 100%.

Whilst reactivity in dogs can leave us all feeling embarrassed and apologetic over our dogs’ emotional behaviour, it is one of the easiest behaviours to address with a gradual programme. It might take some time and commitment, but it is easier to overcome than out-and-out fearfulness, separation anxiety or compulsive behaviours. For the best programme to help your reactive dog, find a BAT-qualified dog trainer, a force-free trainer or an experienced behaviourist to guide you through a personalised programme and help set up your learning events for the dog so that they are not too challenging yet help your dog make good progress. For further information, you can also read here why reactivity can be challenging to overcome with fearful dogs, and how a long exposure to a weak trigger can ensure you see the most progress.

In the next post, how to deal with fear-reactive dogs in ways that help them understand the universe is not such a bad place.