I’ve been having a very serious think about a problem recently. I said in the first of these two posts about responsible sheltering practices that these were probably the two most important posts I’d ever write.

Last week, I took you through the problems. Today, I take you through some solutions. Grab a brew and a snack – this is going to be long.

In the last post, I took you through some of the cultural and social practices that create specific problems in certain Westernised countries, meaning there is a demand for dogs and that would-be adopters are then pushed into adopting a puppy or adult dog from abroad that they can be ill-equipped to cope with.

Ultimately, animal adoptions are a supply-and-demand market like anything else.

There are so many problems that have contributed to the current problems as I see it from my own understanding of European shelter systems and our management of roaming dogs.

Firstly, the cultural and sometimes legal situations that mean there are high numbers of certain breeds that are often considered undesirable by the adopters in the area.

Shelters may be full, but just not with the kind of dogs that people want to adopt. That in itself is a perception issue deeply rooted in cultural beliefs. Shelters try and change this sometimes but all it leads to is mythologising about the ‘couch potato’ greyhound and the ‘nanny dog’ pit bull or Staffordshire bull terrier. These myths often contribute further to the problems that dogs have by making people forget that dogs are dogs.

Some US-based studies have therefore suggested de-branding dogs and stopping labelling them as This X or That X, and that this would improve adoptions. These studies are all very well but they run against common sense. They assume people can’t recognise scenthounds or shepherds or lurchers or staffie crosses or pit bull mixes when they see them. In my view it’s akin to people saying, ‘I don’t see colour or gender or sexual orientation’.

It’s like that Magritte image of a pipe under which he painted ceci n’est pas une pipe. This isn’t a pipe. Clever, artistically, but we all know it is a bloody pipe, if not an image of one. If you don’t bother saying the dog you have is a setter, people will know anyway.

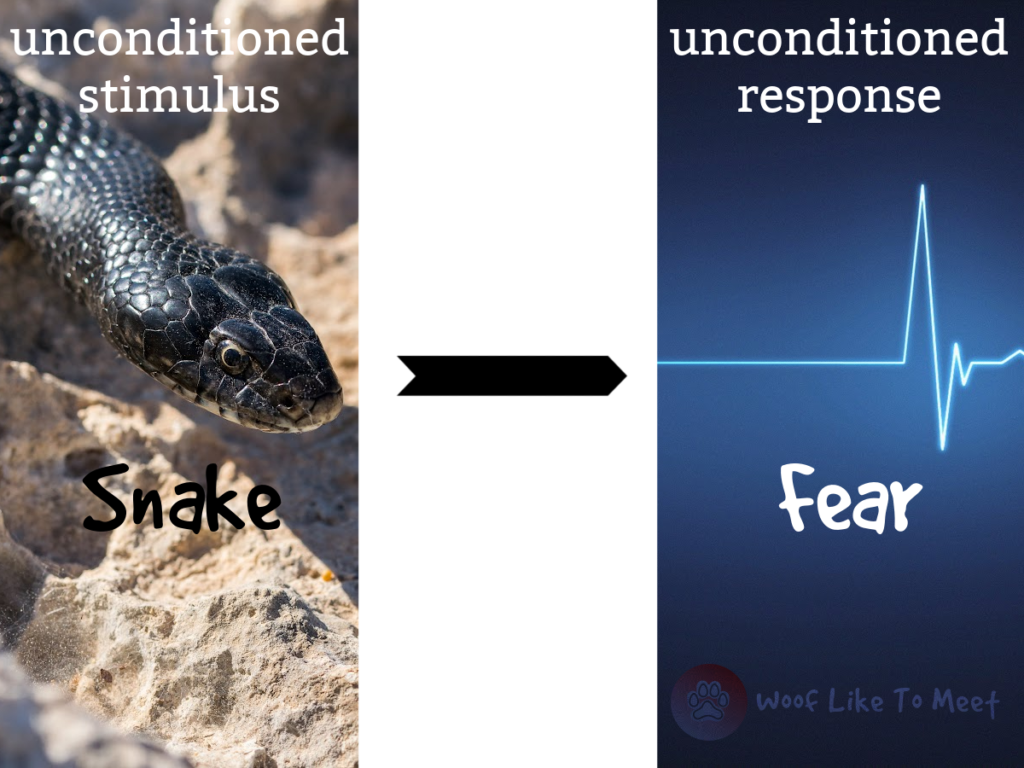

Also, I’d argue very strongly that people do need to understand that human beings have spent a long time tinkering with canine behaviour. The in-breeding that has happened as a result has messed with dogs’ inherited behaviours. No good someone in a shelter saying, ‘Oh, he’s just a dog’ when you’re just about to adopt a working collie with a hundred generations of genes selected for controlling the movement of other things. In Europe, where few dogs exist simply for being dogs and where every country has its mastiffs and livestock guardians, its herders, drovers, protection dogs, hunting dogs and terriers, I’d argue hugely and strongly that it’s actually harming dogs’ welfare not to place such dogs with people who don’t understand that, although not all greyhounds are going to chase small furries, that they’re more likely than your average bichon, especially when they’re stressed. If you don’t understand that a couple of thousand years of loose genetic selection and then a couple of hundred years of very intense genetic selection went into creating a mastiff or a terrier, then you’re going to cause a lot of problems placing these dogs in homes with naive guardians who have no idea that a malinois may struggle with passing cyclists or with people outside the property.

For me, it’s dangerous to pretend all dogs are the same. Fine if they’ve been left to make their own reproductive choices in a free-ranging population for the last hundred years, but that’s not most of the dogs in our shelters in Europe.

Tempting as it is to get rid of breed or type labels, people will recognise they’re looking at a hovawart or a Britanny spaniel. Not only that, I’d argue that, as shelters, we’re doing both our dogs and our adopters a disservice to pretend otherwise. Sometimes, it’s part of careful adoption procedures with certain dogs whose breed-specific traits are very strong that they go into homes with experienced guardians who know what they’re getting. Breed-specific traits are all a bit meh until you get a dog having problems. Then, I’d argue that the way those problems are exhibited are very breed-specific. Most of the time, they’re just ‘dog’ like every other dog. When they’re struggling, they suddenly become much more German shepherd or podenco than they were.

Secondly, we need to accept that there are now social pressures that mean adoption is now seen as the ethical way of sourcing a dog. These social pressures are compounded by social media campaigns encouraging adoption as if it is the only acceptable way to acquire a companion animal. We like living with companion animals. We just feel uncomfortable about buying another soul. I’d even go as far as suggesting breeds and breeders have image issues themselves which is perhaps why so many people – including many very good friends of mine – have opted for modern hybrids.

The increasing costs of adopting dogs with kennel club papers or even just your average run-of-the-mill dog without a pedigree can also mean families are then pushed towards ‘cheaper’ dogs, be they from a shelter or from a backyard breeder hoping to make a quick buck. Again, those are social and cultural issues, since cockerpoos and £4000 pointers don’t exist in France. Well, there may well be cockerpoos, but they’re not a ‘designer’ breed… and a 4000€ dog would have to be really, really good at their job. That said, your typical non-pedigree bichon from a backyard breeder in France is now pushing 1500€ – hence why I have a list of about 50 people waiting for a ‘small, young female’. The cost of dogs reflects their increasing scarcity. You can only sell a puppy for £4000 if people will pay that.

Couple rising costs with increasing pressures about ethical ways of finding a companion, and you can see the issue.

These are not easy problems to solve. Some of them would involve systemic legal change at a governmental level and would be almost impossible to police. They’d also involve cultural change from the ground up, and that’s hard to engineer. Imposed change, like the UK 1991 Dangerous Dogs Act laws can be undertaken quickly; with a Parliamentary majority, they can be passed quickly. However, top down legal impositions that force citizens into compliance can’t always fight easily against culture. If it could, there’d be no banned breeds or types in the UK, as in the other countries where breed-specific legislation exists.

So there’s that. 30 years of BSL tells us that imposed compliance doesn’t work against cultural values.

We need both to make an impact: top-down laws and grassroots cultural change. Shelters can’t do anything other than mop up if laws are not in place and there are also overwhelming cultural pressures that work on the other human behaviour lever: social conformity.

There are huge demands in some Western countries for dogs, and a limited supply. Despite recent laws in the UK such as Lucy’s Law, now also finding an impact in French law too, cultural pressures mean that people still find it desirable to want certain types of dogs and dismiss others. Even though there are strict importation laws across Europe, the fact that there is a higher demand for dogs than there is a supply means backyard breeders will find legal loopholes or straight out break the law, and importers will do the same. Laws will never fight against cultural pressure.

On the other hand, where cultural tastes change, laws don’t need to be implemented. Take, for instance, the fact that many British people stopped eating rabbit and goat in the 1950s and 1960s, and no law had to be passed in the UK to make that so. Gradually we stopped eating bunnies. No laws required that. There’s now a bounce-back for trends in eating rabbit and goat in the UK as niche markets grow again. Culture matters hugely, much more than laws. Ultimately, conformity trumps compliance where humans are concerned. We do what other people do, not what the law requires us to do.

Given ethical, financial and legal issues in the ways in which dogs can be acquired, it makes it harder and harder for families to make the right choices when finding a family companion. With legal changes to make it more restrictive for breeders and importers, demand outstrips supply more than ever. With cultural pressures making adoption more fashionable, that’s another added problem, especially where local adoption practices are overly restrictive.

Couple these issues with problems in other countries and you can see how foreign adoptions intensify to meet market needs.

Shelters in Westernised countries can also worsen this supply problem by overly strict adoption policies with blanket policies regarding how long dogs should be left for or how old children in the home should be are often met with an outright ‘no’.

This too has complex reasons underpinning it. If the shelter is part of a franchise, sometimes they have to follow in line with franchise policies. There are legal issues to consider along with the social media storm that would inevitably arise should a dog from a well-known franchise be involved in an incident that catches the attention of the media. No shelter wants to be at the centre of a media storm involving one of their adopted dogs.

For us in France, most of our shelters are independent. That means, should the shelter change tune this afternoon on adoption policies, they can enact it this very afternoon. Franchises are often beset by complex issues that mean it’s complicated to do so. The advantage of belonging to a franchise is financial. It also provides a support network. The disadvantages mean supporting pessimistic and restrictive company policies at times, and risking losing your franchise licence if you don’t. But it’s harder and harder for independent shelters to stay afloat in an environment swamped by well-paid professional marketers from large franchise shelter chains.

Reputation can be a tension for all shelters, franchise or not. It may not surprise you to know that some franchises or large well-known independent shelters euthanise almost all dogs who enter simply because they daren’t risk a story about one of their dogs biting. Not only do they therefore have to be really selective about which dogs they adopt out, but which people they adopt to. Any risk at all is a barrier.

Reputation also affects marketing. Franchises usually have marketing and social media teams in paid jobs. Independent shelters rely on people donating their time and services. Thus, independents tend to be poorer and have less impact on social media, but at the same time, their reputation can also be affected by public opinion. The more staff you pay to be in the public eye, the more you need your dogs to be easy adoptions, your families to be easy to adopt to and the more the press matters. These all affect the shelter or rescue’s choices.

Where reputation matters to large franchises in the public eye and might lead them to blanket refusals to certain members of their community who rent, who don’t have much disposible income, who work out of the home or who have children, smaller independent shelters suffer from a lack of resources.

Having blanket policies is necessary if you don’t have the resources to ensure that you can manage case-by-case adoptions. If you haven’t time or resources to match up adopters to dogs, then you aren’t in a position to do case-by-case, and that’s fine.

Ironically, shelters or rescues in this position would probably rehome MORE dogs if they stepped away from blanket refusals, but at the same time, there are also independent shelters or rescues who rehome many dogs because they don’t have any barriers to adoption at all, and probably, as I explained in the last post, operate more like Ali Baba and Wish, making it hard to return dogs who aren’t fitting in. This isn’t helpful either.

Operating with no returns and no comeback is easy to do if you’re some kind of nebulous, faceless organisation that doesn’t seem to have any physical structure, and it’s easy to do if you’re abroad. It’s not so easy to do if you have a physical structure and actual people the public can make contact with.

If we have a ‘problem’ dog and the adopters want to make a fuss, for instance, they can simply come down to the shelter with the local press who are always happy to join in. Instead, where there are no returns, adopters are often left with euthanasia as their only option. There is very little data about how many foreign rescue dogs are euthanised, or the problems they encounter. We simply don’t know how big this problem is. Lack of data is in itself an issue. It could be a tiny problem and people’s perceptions about foreign rescues might be completely out of proportion with reality. Ironically, foreign rescues are often tarred with the same brush as foreign migrants. The media (and social media!) goes nuts when any foreigner transgresses, failing to see how susceptible humans are to ‘in-group/out-group’ biases. On the other hand, what behaviour consultants, trainers and vets suspect about the failure of foreign rescue dogs to integrate might be only the tip of the iceberg. We don’t know and the sparsity of data is a real issue. This is an issue that actually has a simple solution, as you’ll see.

For many reasons, then, that are much more complicated than I could every say in some post here, shelters have blanket policies that end up with people looking elsewhere who are then exploited by less scrupulous organisations.

Ironically, if local shelter adoption policies were more liberal, there would be less room for exploitation of dogs from other countries, sold on to people thoughtlessly to fill a need.

It can feel like a Catch-22 for many shelters. You’re damned if you have a liberal adoption policy and you’re damned if you don’t.

How can shelters and rescue associations cope better then, so they have time to move to case-by-case?

First is for shelters to stop running around like your hair is on fire and helping when you don’t have capacity.

Most of us in shelters don’t have capacity. Most of us are indeed running around like our hair is on fire and we’re trying to put out fires in other people’s hair. We don’t have the money to have as many staff as we need. We don’t have the money for big enough kennels. We don’t have the money to hire dedicated marketing and social media presences or people to go round suggesting people leave us stuff in their will. We don’t have the money for vet bills. Yet we feel like we should do something to help if we can. Catch 22. The idea that we can help seems preposterous.

Building capacity can feel almost impossible for shelters.

Shelters can build capacity in two main ways. The first is to become a truly functional hub of the community. The more people who know about you, the more volunteers you get, the more donations you get, the more help you get, the more word-of-mouth you get.

Opening up to the community on your doorstep and working with them rather than cutting yourself off from them is vital.

Serving the community rather than saving their dogs actually ends up saving their dogs.

Sterilisation programmes run more effectively.

The shelter ends up supporting rather than mopping up.

It affords you the flexibility to be pro-active rather than reactive.

You have to be visible, friendly, open, caring, supportive and valued.

Good luck achieving this!

I say this knowing full well that it’s an aspiration.

Sometimes this means finding more central facilities in your local area to be more public. You don’t have to have dogs or cats present – that often ends up a liability. But you do need to be visible and to truly serve the community. Often, shelters are liminal structures, trapped on the outskirts of towns, hidden away as dirty secrets. That has to change. Walls have to come down, and I mean literal walls as well as metaphorical ones. Shelters have to be visible, and not just to people 5000 miles away on social media.

The other way you can build capacity is to work with other shelters, both near and far. I know a lot of shelters do this already. It’s one reason franchises can be popular if they encourage inter-shelter transfers. It really is a life saver. Being able to count on partners who can when you cannot makes a difference. Knowing that this type of dog or that type of dog will be adopted in an afternoon from X or Y shelter makes it a lot easier in many ways. If there are problems, the other shelter are there, on site, to deal with it. When you have reliable, trusted partners, you know that they won’t leave your animals in the lurch. Being able to hit a panic button one Monday afternoon and say, ‘We have ten dogs over capacity’ knowing that five neighbouring shelters will step up and say, ‘We can take three’ literally saves lives.

It can save you having to deal with problems with the community if you can send seized dogs 500 miles away. It can also help if you end up having to take on a lot of animals and you really do have your hair on fire.

It works even better if you know the other shelters and they know you. As a shelter, when you know that X or Y shelter is really, really good at moving on this or that type of dog, then freeing up space keeps things manageable. It stops staff becoming overwhelmed. It stops you using the kennel that really needs some maintenance. It stops you putting dogs in that kennel because you don’t have anywhere else, dogs that you then end up having to treat for injuries and keep longer because they caught themselves on some unfinished metal or something. Working slightly under capacity at all times makes things so much easier. Inter-shelter transfer can be a large part of that.

It’s ridiculous really. When I see all the lurchers and greyhounds in UK rescues, I know that many would be adopted in France in a heartbeat. I saw two whippets in a shelter the other day in France and I bet they went that afternoon. Also, I know that many dogo argentino are euthanised in the UK and are not subject to breed-specific legislation in France… sending dogs to places they are not stigmatised or overly-populous is one way shelters can support each other. We can all help with that.

It’s for this reason many French hounds find their way from French shelters up to German shelters. In Germany, there is no stigma to adopting a regal Anglo-Français hound, an Ariègeois or a Bleu de Gascogne. Shelters in France have the reassurance to know the dogs won’t end up in a concrete kennel outside and used for hunting ten times a year. German shelters have the reassurance of knowing our Anglos are robust, mentally sound dogs who take to German life as if they were born to it. They rely on us to send them detailed portraits of the dogs beforehand and they trust us not to send them dogs that will languish in their shelter for behavioural reasons. The Germans know what the French haven’t accepted yet: hounds make AMAZING house dogs on the whole. Our inter-shelter network depends entirely on trust, communication and collaboration shared by people chasing the same cause: the protection of animals, wherever they may have come from.

Having a good relationship with other shelters is vital. Thankfully there are hundreds of people behind the scenes oiling the machinery. Shelter-to-shelter, rescue-to-rescue, or well-educated foster networks are ideal. Actually, this is often the only totally legal way to act in Europe given the Balai directive and TRACES if you want to do foreign adoptions anyway. If we want UK vets to stop going nuts about the risks of leish or rabies or ticks or blah blah blah, then shelter-to-shelter makes that easier, since the shelter has the facilities to isolate the dog and should have disease protocols in place anyway. The sad fact is that one too many UK vets seem to think all foreign imports are bedevilled with disease or beset by behaviour problems. I know I’ve had UK clients whose vets have insisted on their French dog having thousands of pounds worth of tests for stuff that doesn’t even exist in France just because they were adopted ‘from abroad’ and all that was wrong with the dog was a food allergy. The Balai directive and TRACES is designed to function with disease management and clear pathways for animal transportation in mind. They are designed to function from institution to institution. This is another reason we need to step away from foreign-shelter-to-home direct adoptions, even if they are negotiated by associations who run without foster networks or physical structures. Obviously, this is a very EU-driven process, but other countries have similar import structures where shelters can perhaps act as quarantine kennels just as EU shelters sometimes do.

Another reason shelters should network is that when you have an influx of dogs, you don’t get overwhelmed. Having connections in-country and out-of-country is vital. We’re not working in isolation.

It’s not only the safe and legal passage of the dog from shelter to shelter, but also the passage of information. I can’t even begin to tell you how much work goes on behind the scenes from our multilingual supporters who make sure videos are passed on – nay, demand videos. They want inside leg measurements and the height of the dog and the dog to be measured up from every angle. I jest, of course, kind of. I’m not the only person to have a tape measure in my pocket because someone’s demanded measurements for a harness before a dog arrives in their country, or the transporter needs to know how big the crate should be. I’ve also translated veterinary documents, as have many of the other elves. Shelters hold enormous rafts of information on the animals in our care. Making sure the next shelter gets that information is crucial. It also helps them place the dog safely in their shelter.

When foreign rescues go from their shelter to a shelter in another country, it’s not just data about the dog in themselves, but the population of dogs. Shelters collect lots of data. We’re awash with it. When we act as a hub for foreign dogs coming in, that means there is an easier way of collecting data about health and disease, rather than trying to collect data from 4000 adopters who may or may not respond. It also means ease of collecting data in terms of how many dogs are returned to the shelter for whatever reason.

How can we know if foreign rescues are really a problem? We can’t when we’re just working off anecdote. People say the plural of anecdote is data. It isn’t. It’s anecdotes. We still don’t know. We need actual crunchable data that it’s impossible to get through owner-reported surveys. You want to know how many dogs are rehomed once they arrive on foreign shores? You can’t know through asking people to tell you. You want to know how many dogs of foreign origins are euthanised by vets as a result of disease or behavioural problems? You can’t know by asking vets to self report. Only the vets with a vested interest one way or another will reply. That data is so dirty and so flawed as to be useless.

Where dogs come into foreign shelters or are managed by robust foster machines, that data is much more easy to access. Want to know how many of our shelter dogs are returned in a year? I can tell you that. How many days they were in the shelter? I got that too. How many had a behavioural issue? I got that. How many just didn’t gel in their family? I’ve got that data. How many were euthanised for behavioural reasons within six months of adoption? I’ve got that.

Shelters can act as hubs for better data collection, not just in terms of understanding the problems with foreign adoptions – if there truly are any out of proportion with ‘homegrown’ dogs – but also in terms of health data on diseases such as tick-borne disease and leishmaniasis. When dogs are transferred across borders, there are many, many reasons that shelter-shelter transfers are a better solution. Or, at least, shelter-foster network.

It’s not just about data. Shelter-shelter transfers are also about support. When shelters act as a hub for dogs who’ve travelled from further afield, they also take charge of the after-adoption stuff. Dogs don’t always fit in. That’s a fact of life. I’ve taken back three fosters who just couldn’t live with my dogs or my lifestyle. It’s made me heartbroken to do it. Sometimes things just don’t work out. Returning a dog 10 miles to a place that has the capacity to take them takes a lot of the pressure off.

One thing is for sure: shelters need to be open to the community so that returns can happen easily. Better a dog has a short return to kennels before being rehomed than a long and miserable life with thousands of pounds spent trying to make a round peg fit into a square hole. That can’t happen easily if the shelter is 2000 miles away. That’s another reason shelters need more local hubs who have capacity to take dogs back if necessary. Again, if you’re running around with your hair on fire trying to put out other fires, you probably don’t have capacity to do that, and no judgement is intended. We’ve had Mondays where four dogs have been returned. If you can’t take in four dogs because you’re at full capacity – if you can’t even take one single dog back because you’re at full capacity – then you’re not positioned to be open. Networking would help with that.

Foreign adoptions can be just marvellous. Dogs who have no chance of a short stay in your shelter can find places where they’d disappear in an afternoon. There are literally waiting lists for obscure French hounds in Germany, so beloved are they. The main reason is they are amazing dogs who should disappear out of all shelters in a heartbeat. Those dogs would languish in the shelter in France.

However, it also depends on us knowing what kind of dogs are easily adoptable and also don’t have difficulty integrating into German life. If shelters and rescues just offload their most difficult dogs to adopt, then they’ll soon get a reputation and nobody will take dogs from them.

Inter-shelter transfers within or across borders can also help you develop capacity so that your own shelter can help. It doesn’t make a difference if that’s within your own country or across borders where the dogs won’t face massive problems adjusting.

If you’ve sent five dogs to another local shelter who can help, if you’ve sent ten up to another shelter across the border where they’ll be rehomed in an instant, then when your neighbour rings up with five staffies, you’ve got capacity to say yes. We can’t win the war if we’re all fighting our own battles. Easier said than done, I know. As I said, aspirations, on the whole.

Opening up isn’t just about opening up link from one organisation to another.

It’s also about opening up to your community.

Again, easier said than done. The good thing is that many European shelters are already dipping a toe in the water, if they aren’t fully signed up to the process. Many of us are building capacity little by little and helping out where we can. We can do more when we work openly and we involve the local community.

Serving the community and rehoming responsibly aren’t always easy. Of course you can create a presence and market the heck out of yourselves, but it’s also about being open. There are a gazillion ways people can support their local shelters and associations, most of which do not involve being physically present at the shelter. It’s easy to write off the community around the shelter as being irresponsible, causing all the problems you’re in the business of cleaning up daily. Yet engaging people in the shelter is one of the fastest ways to spread the message and to change people’s opinions, not just about the dogs that you have for adoption, but also changing people’s perceptions about the shelter.

Many shelters in the past were responsible for the management and death of stray populations; many still are.

It’s not that they want to be – nobody really wants to kill dogs for a living, do they? – but the image of kill shelters lingers to such an extent that people are adopting from noisy, social media savvy foreign ‘kill stations’ because they want to save the life of a dog without realising that the shelter just up the road from them is having to do the same.

It works in other ways too. If you’ve worked hard to move away from euthanising a surplus of animals, it’s soul-destroying to have community members who believe you’re still in the business of having to kill dogs and cats.

How do you help people in your community understand your shelter’s missions and stop populating myths?

You open your doors. Even just a chink.

That of course means opening yourself up to both scrutiny and criticism.

At the same time, it’s well known that it’s easy to live with irrational views when you aren’t faced with grim realities. For instance, I’m sure the myth about breeders being responsible for dogs in shelters would be soon put to bed in France if people realised that viewing dogs as a utility does much more damage. If only we were overwhelmed by ill-bred dogs with paperwork every day! I mean the Australian shepherd is France’s most popular breed right now. Last time we had one in?

Not to my knowledge.

I know we’ve had the accidental offspring of Aussies, but we’ve never had one in, despite the fact I know personally of one family who’ve had six ‘accidental’ litters of mixed breed pups by letting their unsterilised female wander around when she’s in heat. Not one of those dogs ever came into the shelter.

If you’re going to tackle myths, present the grim reality, and you’re really going to start bringing down the cultural institutions that truly put dogs in your shelters, you need people in your community to know what’s happening rather than pretending that it doesn’t or blaming people who contribute to the problem. It’s not just that countries need to fix their own issues before shipping off strays, but that communities do too.

If we want to change cultural values, we have to move out of the world of nebulous biases, prejudices and stereotypes that fester away causing fears to worsen. We can do that by being open and by being rational. Data helps us do that. Shedding a light on things and being open to what the real picture is helps enormously. The more people involved in your shelter, the more myths you can bust day after day.

Besides networking and opening doors, another thing that makes a huge difference is for shelters to take the view that they not only should serve the community but support the community.

Our shelter faces three groups of people who contribute significant numbers of dogs to our animal population for various reasons. Having close links with these groups can be mutually beneficial even though it’s tough. It’s easy to alienate and ostracise groups who view animals differently than you do, but many of the problems that arise are through over-population or lack of support, both of which can be helped by being in and around the community as problems emerge, rather than when problems reach a point where they can’t be easily resolved. Keeping dogs in their homes can be a really sensible way of keeping them out of shelters.

Being in touch and working as a multidisciplinary team with health professionals and social care teams can also help. If teams working to support the homeless know they can turn to the shelter for food, for low-cost veterinary care or sterilisation programmes, or even for temporary lodgings, that can also help fulfil a more supportive role. Shelters can lead by example rather than closing the door.

Of course, this can make people dependent on shelters to clear up after them… there’s people who argue that problems exist because shelters exist… children with elderly relatives will run the appeals and find their dog a home rather than letting the dog go to a shelter, or families will step up to help with vet care, but I think this harks back to days when shelters killed surplus populations and there weren’t treatments for various diseases. Society is more fractured these days and a wider range of people live with dogs. It’s not as simple as saying problems wouldn’t exist if shelters didn’t exist.

Generally things don’t happen overnight. Situations don’t happen overnight and trying to fix them overnight doesn’t help either. Often, when healthcare professionals can alert shelters and rescues before beloved pets are going to be relinquished it also makes the transition of the guardian into medical facilities or nursing homes much easier. Likewise, rather than having 30 puppies over 18 months, if social services let shelters and rescues know as soon as the first litter is born, shelters are better placed to rehome litters and to make sure sterilisations, vaccinations and microchipping can be carried out.

But, as the saying goes, it takes a village.

Shelters and rescues need to be a focal part of that village, rather than remaining on the outskirts, as liminal as the populations they often serve. It’s worth reiterating that sometimes things need to change at a national level otherwise we’ll always just be mopping up problems elsewhere on this planet, but the same thing is true of our own communities. If we’re having to rely on inter-shelter adoptions, we’re really just farming out our problems elsewhere. However, if you need to deal with problems in your own region, then you need to work under capacity as a shelter so you can get out into the community and spend resources there rather than on in the shelter. That may need a lot of support at the beginning.

When shelters have capacity and when they work as a network to move dogs to where they can most easily be adopted and supported, then that frees up other potential too.

What’s most important, I feel, is that we don’t pull the ladder up behind us having been given a helping hand out of the pit of despair.

You might be doing a very nice job of keeping your own fires under wraps and may not have run around with your hair on fire for many years. But if everyone around you is on fire, then there’s something of a duty to help out.

It’s never comfortable for shelters to look at their own populations and think they too can be involved in supporting foreign or even other local rescues. I’m sure our German, Austrian, Swiss and Luxembourgish partner shelters, associations and rescues could easily say that they don’t have capacity to help us out. If you ask me if I want to take five dogs a month from countries having bigger problems than we face, then if we’re in a position to, we absolutely would. That said, according to many media sources in France, France has the biggest shelter population in Europe, so we’re no role model. Despite this, there are still times we help out our neighbours. No reason those neighbours need to be on the same side of the border as us.

So shelters can work differently and can change. It would make a huge impact and reduce a great deal of problems if we did. Many, many shelters in France are already doing just that. I’m amazed by how much collaboration and support already happens within and across borders. I’m not writing this as some vague dream, but based on the practical experience of the shelters and associations around me who are already doing these things.

If shelters want to do our bit to reduce the pressure on the supply-demand market of dogs, we need to change our way of working. Hard as it is. Knowing full well we’re all still running around with our hair on fire most of the time. That’s a given.

Shifting to case-by-case adoptions and having an open door policy for trial adoptions makes a real difference.

This might begin to change things in our own locations as well as position the shelter more centrally in a post-humanist world. Who knows whether shelters will form part of integrated community support hubs in future worlds? I can dream…

It’s all well doing more within the community, but our reach might be better if it doesn’t end there.

I think if shelters were open to taking on inter-shelter adoptions, especially from other countries, we could really change things. Even if we’re all just doing a tiny bit.

Other things need to stop, though, in the rescue world. This is rarely of the shelter’s making, although restrictive adoption policies and an over-population of particular breeds or types of dog definitely create a situation in which other problems then occur.

What we know categorically doesn’t work (and is borderline illegal in the EU) is adoptions from foreign shelters direct to homes. Not by the intermediary of a physical structure; nor by the intermediary of an experienced foster network. From a foreign shelter or home direct into a home in a different country.

This system is the one most likely to fail. Like it or not, anyone can set themselves up as a rescue, can fundraise (and spend funds how they please) and can find some desperate shelter somewhere else on the globe to ship them dogs. While they might arrange transport and take payment from adopters, even passing on some of their funds to the original shelter, they don’t have the capacity to help when the dog arrives because they don’t have a physical structure or a foster network that acts as one.

They’re often not even there when the dogs arrive. They don’t know the dogs. They may have published stories about the provenance of these dogs in order to find them homes – often accompanied by KILL SHELTER!! and things in capital letters with lots of exclamation marks.

This is not responsible rescue.

At best, most of it loosely works out, on an Ali Baba or Wish kind of model. You weren’t really warned what you were getting. It wasn’t what you wanted. The dog copes if you’re lucky and there’s nowhere to return the dog to if they don’t cope.

Direct adoptions from foreign shelters might solve the occasional problem. They don’t solve anything significant and it mostly ends up mopping up some situations to help out shelters who appear to need it. At worst, it’s responsible for those countries letting dogs proliferate as a fundraising tool because they know some rescues act as if puppies are blank slates. It’s what causes fury over the abuse of international animal transportation, import, export and sales laws and leads to claims that such transport and transfer systems are unworkable.

It makes me sad because I know the vast majority of places operating a direct-from-rescue service mean well. I know most do. Sadly, many are run by people whose hearts are bigger than their experience or capacity. I’m sure they do not mean to put dogs into homes who are going to spend three months under the table, often needing extensive training and medication just to even cope with daily life, let alone to live a life worth living. Let’s be clear: our local dogs, even dogs from great breeders can suffer serious separation anxiety, fearfulness, aggression or extreme lack of socialisation. It’s not new and it’s not limited to foreign dogs coming to foreign shores.

The sad fact is, though, that many puppies from foreign shores are sold as if they are blank slates by well-meaning people who think that love is enough and if the dog has a roof over their heads, then the ends justify any means. When there are problems, they don’t have back-up and they don’t offer support, only condemnation and blame for their ‘failure’.

This is another reason shelters are often better placed to help: knowledge of dogs, puppies, socialisation, behavioural traits, training and handling dogs is a skill that direct-to-home networks don’t always have. Shelters are often better placed with professionals who understand that puppies aren’t blank slates and are more experienced at handling dogs as well as working with dogs with traumatic pasts.

The belief that love is enough and that puppies are blank slates is leading to a very high number of puppy adoptions that are just not working out, unfortunately. Don’t get me wrong: there are plenty of purpose-bred dogs that also end up in the wrong homes: the care to match people with dogs isn’t always rigorous, no matter where the dogs come from.

Sadly, though, in my opinion, there is little less responsible than taking a puppy with a genetic legacy of 3000 years of utility as a guardian breed and giving it to guardians who have no idea what they’re getting or why they’re having the problems they’re having. Having had clients who’ve never had dogs before, have never had guardian breeds before, who’ve never had a puppy before, the ramifications of selling puppies from foreign countries as if they are blank slates are enormous.

These are the clients I spend the first hour with giving them insights into the dog they just picked up. Welcome to life with a spooky Carpathian shepherd whose job it is to tell you that wolves are after your sheep and alert their family. Welcome to life with a GSD from very strong protection lines. Welcome to life with a working Labrit, an out-of-sorts Grand Pyrenean, an imported Akbash.

Nobody should get one of these dogs without at least knowing what it means or how dogs like this have mostly lived and what they may struggle with. The same is true with any dog to be honest. I look back at myself ten years ago and wonder what was going through my tiny mind to adopt dogs with such a blasé attitude. They’re just dogs, right? How hard can it be?

Luckily, the behavioural and medical problems that my adopted American cocker spaniel had were exactly the same problems that my Nana’s American cocker spaniel had some thirty years before. Like I said, breed matters, especially when it comes to problems.

Honestly, and I feel really strongly about this, if an adopted dog is placed in an inexperienced home, these clients shouldn’t be having to pay for my time. It comes back to shelters having the right to say no (and, perhaps, not exercising it quite so liberally at times, I know…)

The rescue should be providing support. I do it when other associations and shelters ask me to because I enjoy doing it and I’m glad to be asked. A dog from a shelter 300 miles away is no different than a dog from our own shelter. Just because the ink is dry on the contract doesn’t mean the relationship is over. Adoption should be a lifelong relationship, not a sales contract. This is also easier to achieve when you are working locally. I can’t tell you how great it is to see ‘our’ dogs out at the park, on hikes, on walks, at the shops, visiting the shelter, coming for open days. I also can’t tell you how happy I am to be involved in their ongoing lives should they have problems fitting in.

As I said, when we have capacity, we help. That can be as individuals or as a shelter.

Since I’m not needed so much, it gives me the flexibility to help other associations and rescues where needed. But I shouldn’t be doing this without the original rescue ‘negotiator’ admitting they need to change their practice. I totally understand why my UK colleagues are getting frustrated because there are unfortunately so many associations acting as nothing more than money-collecting middlemen who facilitate transport and nothing more. They’re procurers or brokers, not rescuers. I realise many mean well, but without a physical location or a robust team of fosterers where there’s slack in the system, meaning well means that many dogs are struggling in families that are ill-equipped to cope. Sadly, an enormous number of these dogs are then euthanised without the broker who brought them to foreign shores accepting responsibility or changing their ways in the future. I guess it can be difficult as well for such procurers to even know how big their problem is if they aren’t aware of how they compare to others

Responsible sheltering might ultimately mean that we’re all able to open our doors from time to time to other shelters who need us to. I have no problems with adoptions to foreign climes: many of the dogs I have known and loved have found homes through our German partners. In turn, we offer space for local shelters here who are overflowing and at risk of being requested to euthanise ‘surplus’ dogs as well as supporting 30 Millions d’Amis and One Voice among others when they don’t have space. If – and when – shelters have capacity, that means being able to act as a hub for dogs coming into the country. I know foster networks who do the same thing. At least there’s slack in these systems. At best, the experience is safer and much less traumatic. It’d be hypocritical of me to accept help from other shelters and not support inter-shelter transfers.

The dogs arrive into safe and experienced conditions. Of course it’s kennels. We understand that. But even from offloading, shelters are ready from the get-go. Who else has 3 metre gates and can find people to be there at 3am when the transport arrives? Who else has handled thousands of dogs both into and out of transport crates? Who else has the physical capacity to cope if the adoption goes wrong? Far better that the dog can be returned to a local shelter than end up on a dog sales site or being euthanised because the guardian feels that they have no options.

Things can be better.

Things are better when we reach out.

I see in the next twenty years that the grown-ups in the shelter world will be having conversations about responsible sheltering. We need to be visionary and we need to work more collaboratively in order to do that.

We can’t do it if we’re all fighting our own fires.

We’re all learning, all the time. We do that faster than any other species because of one thing: language. As one of the youngest species on the planet, our progress has been exponential because we communicate with words. We can use this to benefit the other species our lives have impacted, whose trajectories have been irrevocably altered through domestication, so that they don’t suffer as we all face further challenges in the 21st century caused by huge divides in equity and mounting climate change.

I think we should finish with a message of hope.

I can’t begin to tell you how many amazing people I know in rescue and rehoming. Sure, there are egos and there are people who seem to be scratching psychological itches they’ve not dealt with properly. There are crazy people and passionate people and argumentative people. There aren’t enough of either the amazing people or the passionate people, and shelter work can consume many, many of us and spit out our bones.

Even so… these conversations are already happening – have already happened. These networks already exist. Shelters are already moving to the centre of communities and taking a central role in welfare of all species. It may only be some 200 years since the earliest movements in animal rights and animal welfare began, but in 70 years, we’re already a long way from the dog pound and the mandatory execution of unclaimed strays.

As we climb that ladder of progress, there are two things I think we need to do. One is to share how we’re doing it as shelters and stop being so reticent about it. Others can benefit from our lessons – another great thing about being human. The other thing we need to do is to remember not to pull the ladder up after us. Responsible sheltering doesn’t mean cutting off our neighbours. It means remembering we’re all fighting the same fight and we’re all on the same side. When we work together, we improve our capacity. When we improve our capacity, we can help others. That help needn’t end at our borders. Arguably, it shouldn’t end at our borders.

Ultimately, shelters are one small piece in a very large puzzle. This puzzle is largely given over to legal and cultural behaviours that are beyond our control. That’s not to say shelters haven’t got anything to offer. I truly believe we can go a long way to addressing problems when we remember that borders are artificial constructs and that our relationship with animals is global. We do enough damage cutting ourselves off in human exceptionalism. It’s time to remember that we’re all part of a global system and we can’t just ignore our neighbours’ problems because we think our own problems are unrelated to theirs.

To all those involved who are already making this happen, may you be the vanguard for future ways of working. It’s true what they say: rising tides lift all boats.

Available in ebook form and paperback