When we adopt a dog, what we expect is for them to be happy. We like to think that they get what’s happening and that it’s all blooming marvellous. We tell ourselves that they know what’s going on and that they’re going to love it. Many of us are guilty of thinking that love will be enough and how we handle things after the adoption is unimportant. We’re guilty of thinking that all we need to do is buy a new dog bed, and get a new collar, harness and lead. We concern ourselves with the physical aspects of adoption, not the emotional.

I know. I’ve been that person.

When I adopted Amigo, what I told myself was that he was thinking:

Lady, you are the best person I ever met. I’m going to be such a good boy! We are going to have the most amazing adventures together! I’m just going to lick you and lick you and lick you. Thank you! Thank you so much. See my waggy tail? That’s how happy I am!

What we don’t think is that really, they’re most likely thinking:

Who the hell is this woman? She seems very nice. I wish she’d stop looking at me. Please don’t touch me. Don’t touch me… Don’t touch me. I don’t even know you!!! She’s touching me. I don’t like hands. Hands hurt. Why is she touching me? Where are we going? What’s going on? What’s this tiny thing? What’s that noise? What’s she doing? Where does she want me to sit? It sure smells funny in here. What the f@*&’s that noise? Why is the seat moving? OH MY GOD this thing is moving!!!! I want to get out. Can I get out. How do I get out? Where is the door? How can I get out? Stop touching me! Stop looking at me!

Not only did I pop him in the car, I took him to a new house. I introduced him to new animals. I set him up to be stressed and without really considering it (he was the fifth dog I’d adopted) I didn’t think about the stress he was feeling. It took five months to wrestle him back to a place of calm. Sorry Meegie. I wish I could start again. Luckily, he forgave me for this and the rest of our days were spent building his trust.

The modern world is stressful to a dog. They are living in a world that does not always make sense to them. It’s akin to moving to a different country with a different language and very different customs. Notch that discomfort up a little and you get a sense of what it must be like to live in a dog’s world. If your dog has ever barked at anything new, you may have laughed it off, because we simply don’t know what will freak our dogs out. Tilly spent a good five minutes barking at the washing basket in the garden yesterday. I don’t know why. She’s seen it before. It’s been in the garden before. Nothing was different in most ways than every other time the laundry basket has been in the garden. But yesterday it spooked her. Heston once spent a good while barking at a sieve. A stone cross also freaked him out. Amigo doesn’t like to be inside during storms. Molly used to bark at snowmen. It’s common for dogs to bark at hoovers, lawnmowers and other animals. These are fearful responses to things that don’t make sense to dogs.

But barking is not the only way that we can see an animal is stressed.

Creatures feel fear and have a stress response. This we know. When something makes us feel afraid, our bodies have surprisingly similar responses as a dog’s. Adrenaline is produced. Our heart rate increases. Our brains become less capable of making choices as our fight-or-flight response kicks in. Once the brain says, ‘hey I don’t like this!’ the thalamus gives us a shot of hormones that set us off on a very typical “stress pathway”. Ever tried to reason with someone who’s red in the face? Ever tried to get your dog back under control when they’re barking at a stranger? You’ll know how hard it is to overcome the stress response. It’s not that they’re not listening; it’s that they can’t listen.

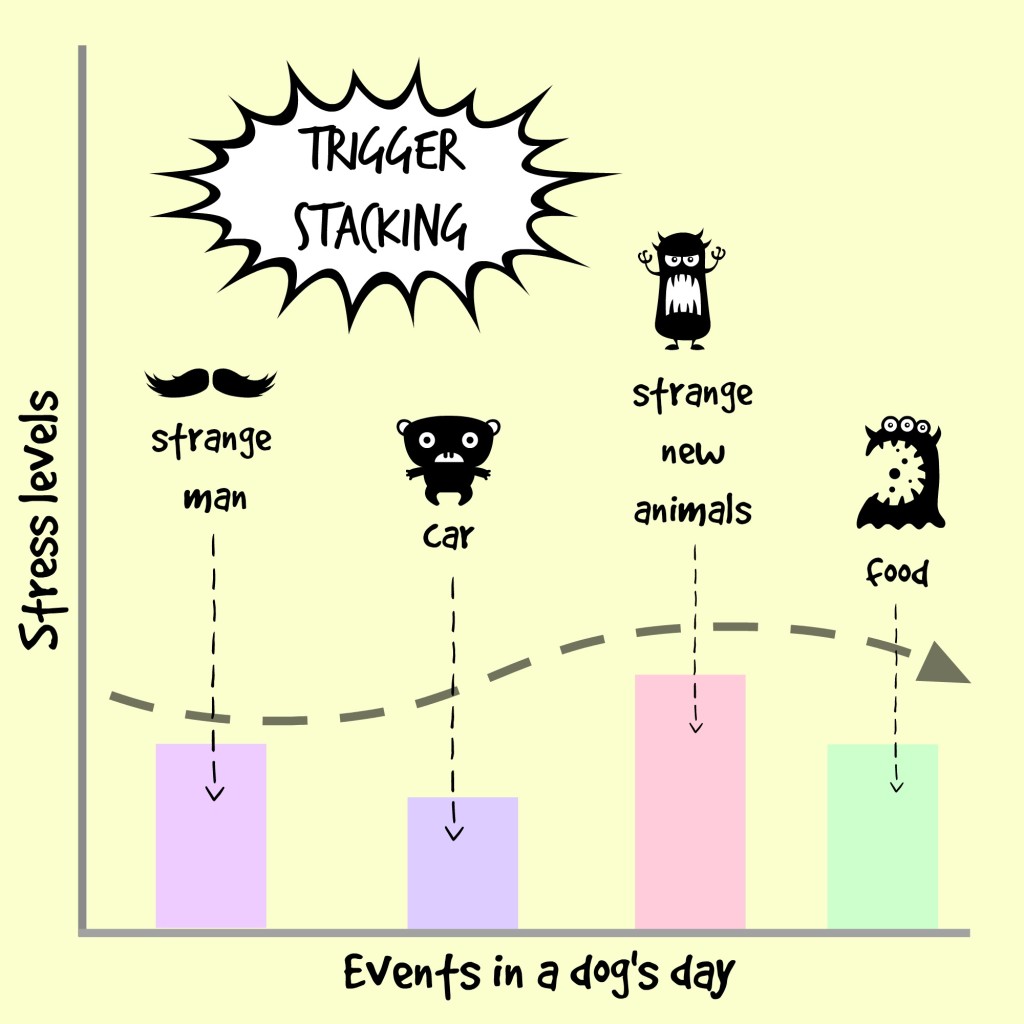

What normally happens in a dog’s ordinary day is that they meet a series of stress-inducing triggers. If you’ve socialised them well and habituated them to these triggers when they are young, they will most probably learn that these things are nothing to be afraid of. If you don’t, you’ve got an uphill battle to show them that a strange man in a hat is nothing to be afraid of. When we adopt an adult dog, we have no idea what they have been socialised with and what is a trigger that sets off that stress response.

For the most part, our dogs meet an unfamiliar trigger and then they move on. They may growl, show their teeth, snap or bark at it as they attempt to “fight” the trigger, or they may run away to a safe distance and hide if they are in “flight” mode. The other week, someone dropped a sack of fertiliser by the side of the field. Heston did both of these things: he stood, he stared, his hackles went up, he growled. The thing didn’t move. He went a little closer and growled more in case it hadn’t heard him. Then he barked at it. It didn’t care. He went closer, barked and then backed off. He did this progressively, getting gradually closer until he’d decided that it was nothing to be scared of, barking, retreating, barking, retreating.

When we start down the stress response pathway, adrenaline is produced to help us run or fight. Cortisol is also produced. This is important and we’ll come back to it later. Normal responses to stress include avoidance (not looking at it, backing off, seeking shelter) defense aggression (growling, snapping, barking) looking for contact with humans or other animals for reassurance (hiding between your legs, often!) seeking attention from a bonded human or animal. When dogs can’t escape or attack, you will see other behaviours too. Lip-licking, flat ears, tense faces, panting, low body posture, seeking escape, slow movements. They may be reluctant to take a treat or they may snatch when they normally wouldn’t. This clearly has implications for positive training and counter-conditioning to overcome the response.

Normally, the trigger goes away and the situation returns to normal. The body stops making stress hormones and within minutes to hours, most of those hormones have dissipated. The dog learns to tolerate these small events and episodes. Cats in the garden, postal workers, teams of cyclists going past… they’re strange and unfamiliar events and your dog will have periods between them to recover.

But what we do with a shelter dog is take an unfamiliar dog and give it a short, sharp shock of everything we know to be stressful. We take a dog who is already stressed. Even two weeks in the shelter is enough to have long-lasting consequences on the stress hormones and body, especially if they have been kept on their own.

Shelters are good at recognising unnatural stress responses for dogs, but there aren’t often solutions to this. Displacement activities may be evident (licking, grooming and eating stuff they shouldn’t) as well as stereotypical responses such as circling, excessive grooming, tail chasing, tail biting, excessive drinking, fence-line running, anorexia or excessive eating (yes, dogs comfort-eat too) and dogs may even hallucinate, chasing imaginary flies or staring into space.

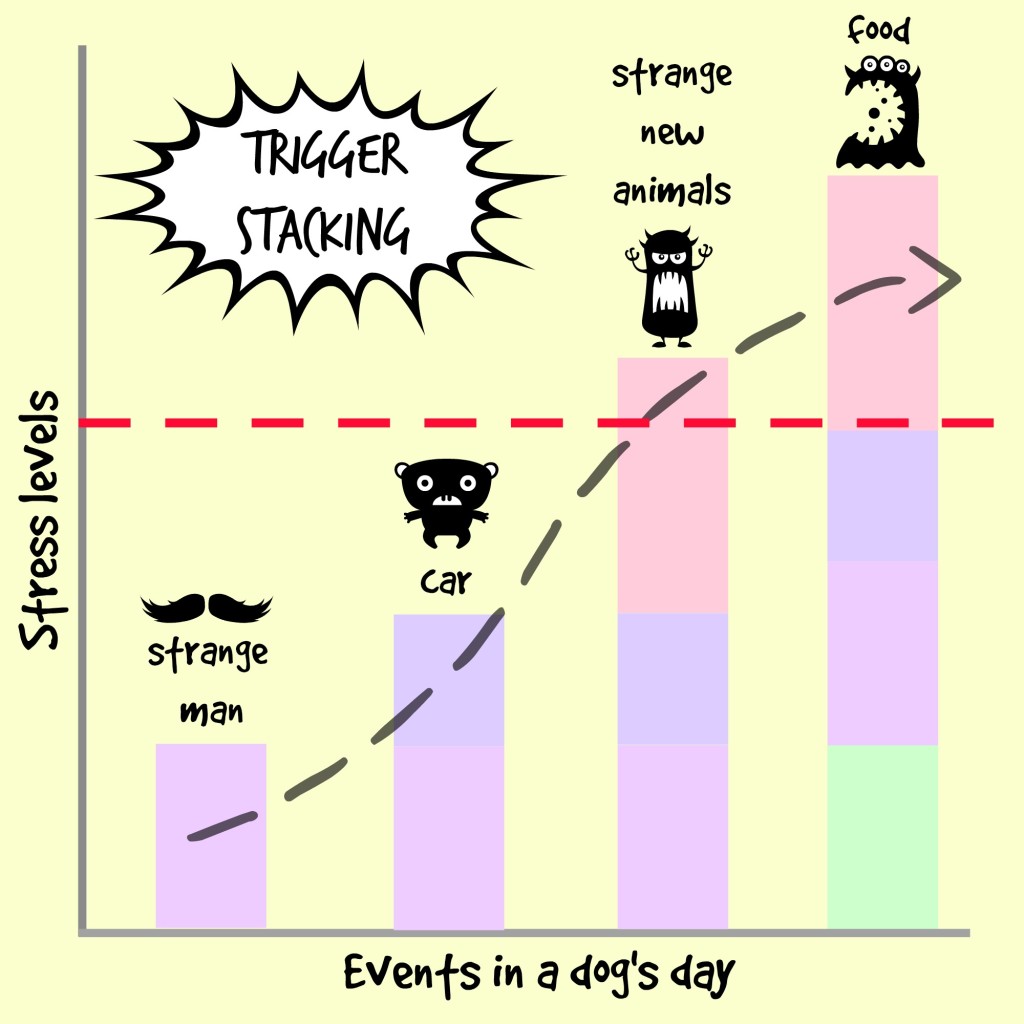

But there are many dogs who do not exhibit such behaviours in kennel environments, and we may be unaware that they are very close to the point at which they cannot control their responses or when it all becomes too much for them. We call this point the “threshold” and it’s marked in red on the diagram below.

When we take a dog and subject it to a range of new and stressful experiences, we stack those triggers all together, and we are not allowing their bodies to deal with the triggers we are subjecting them to. In one short hour, everything changes. They go from an austere environment where the majority of dogs show some signs of stress, and we think that what we are doing is comforting and reassuring. It isn’t. We introduce them to new people. We may put them in a car, which they may never have experienced except for a brief trip to the pound or their journey to the refuge. We take everything in their world and turn it upside down.

And instead of being able to tolerate the stress, we don’t allow sufficient time between all of the changes, and we stack the triggers so that they build up, one on top of another.

Once they pass the red line, you are going to see exaggerated stress responses. Stares and teeth displays or pinned ears and avoidance techniques can turn into defensive attacks. This might just be a good old bark or grumble. They may urinate (I showed Tilly a new dog coat once and she did this…. I called her Tilly Piddle for a reason!) They might “give in” completely, overwhelmed by fear. They may try to run away or hide. In French, we say se sauver, which literally means they try to save themselves. Shutting down completely, trying to escape or behaving offensively when they can’t are all ways dogs can try to deal with threats.

There are lots of things you can do to avoid this situation.

Visiting the refuge often to meet the dog and spending at least an hour with the dog before you adopt them is one of those things. For dogs showing signs of an unnatural stress response (licking or circling, bark displays) you may want to sit in with them for a couple of hours, doing absolutely nothing. Sometimes just being around the dog is enough. Give them time to get used to your smell. Leave some clothes if you’re sure that they won’t shred them, or take some of your dirty laundry and give them time to investigate your t-shirts and pillowcases at a distance from you. We know smell is really important, and we often put our hands out for dogs to smell. Whilst this is incredibly unwise and dogs have absolutely no need for us to put out our hands to smell, the principle is the right one. Quite often, when I meet a strange dog, I just stand and let them give me a very good interrogation. I don’t speak to them. I don’t move. I just stand loosely and neutrally and let them sniff my boots, my jacket and my trousers if they want to approach me. If they don’t, as long as the dog is not likely to take your clothes and tear them apart, putting down some items of clothing or bedding and letting the dog investigate in their own time can really help them get to know you.

You might not want to use food at first. Food can often bring dogs closer to us than they would naturally choose to be. That said, it can speed things up with the right dog. Rather than offering the food from your hand which has the tendency to bring dogs in closer than they might naturally choose to be, try things where you leave the food and where you move away, or where the dog has a chance to move away.

If you’re going to use food, games like ‘Party in my footsteps’ or Suzanne Clothier’s ‘Treat and Retreat’ can help.

Giving them a small amount of high-quality treats will show you that their stress levels have gone down enough to think of moving on to the next stage. You might even want to continue these routines in your home when you get back. Heston accepting treats when he met Tobby was my cue that he was sufficiently unstressed to move in a bit. But take your time. Though the adrenaline will have dispersed, the cortisol will not.

I was also really glad to see a lady taking the time to introduce her new dog to her car, spending a good few minutes over a few days getting him used to being in it, then turning the engine on, and so on. Not all dogs will need this if they have been used to getting in cars as a puppy. I’m pretty sure Heston would hop in anybody’s car given the chance. Cars mean adventures to my dogs because what happens after being the car is 99% good (except those vet trips!) But for a fearful or anxious dog, the guidance she’d received will certainly help the dog feel more comfortable.

If you have other dogs, be careful how you introduce them and take your time. When Tilly and Saffy arrived here after their car journey, I just randomly let them meet Molly, the new house, a whole load of strange men… no wonder Tilly quickly turned to submissive urination and excessive drinking. I’d say it took a good four or five months for her behaviour to return back to “normal”. You know my story of Amigo already. That ended with five months of serious retraining. Ralf… I got smart. Tobby… even smarter. And guess what? Those dogs weren’t stressed out. I doubt whether Ralf ever got stressed, since he was a big, chilled-out mattress-back. Tobby certainly has stress responses: he is happy to run away and he has the potential to bite. But I like to think that I did everything I could to avoid walloping those triggers one on top of each other that first day home.

There is no better guide to introductions than this one from Roz Pooley aka The Mutty Professor, and Rachel Trafford.

It works just as well with newly adopted dogs, with dogs on their own and with dogs who you’re fostering. I really can’t recommend this video enough. It should have two million views by now.

Avoid stacking those triggers and you’ll avoid pushing your dog to the limits of its tolerance. Time and calm is your best friend. Although everyone will want to come round and say hi to your new dog, what is best is a recovery period. Although you may want to give your new dog toys, treats and love, what they need is calm. Perhaps the very best thing you can do is sit very quietly for a couple of hours and read a book whilst they make some sense of their new environment. It’s not exactly what you envisaged, I’m sure, but it’ll help break up those triggers into manageable blocks.

For further guidance you can read:

10 tips to dog-proof your home.

And if you want to know a little more about trigger stacking, this video from trainer Donna Hill will help

If you’re noticing problems like fearfulness, suspected separation-related behaviours, reactivity or aggression in the first few days, make sure you get in touch with a behaviour consultant who can help you out. The shelter may have their own team to help you out, but you can also find reputable trainers through the IAABC and through the Pet Professional Guild as well as the Association of Pet Behaviour Counsellors. There are many good organisations alongside these three. Just make sure your behaviour consultant is committed to the least intrusive and least aversive training methods. Punishment has no place in working with newly rescued dogs. Coercion doesn’t have a place in the training of any dog, but this is especially true of newly rescued dogs.

If you’re a dog trainer and you’re looking to work in more cooperative and less coercive ways with clients, you might want to check out my new book. It’s available on Amazon. Leave me a review if you’ve already read it!