Most of the time, we shelter folk have to exercise a higher level of restraint than the general public. Most of the time, we manage. We manage to grit our teeth and not let the emotions spill out when someone says they’re surrendering their dog because it snapped at their child. Perfectly reasonable. Until you hear the circumstances. The child was pulling the dog’s ears to get the dog out of its bed.

All you can do is nod politely when in your head you are looking at the dog thinking, “You amazing creature. You could have bitten the child and you – you! – showed restraint! I’m so sorry that it ended like this for you, but I promise to do my best to find you a family where nobody will pull your ears and where there are people who understand animals.”

That’s hard for most people to get their head around.

How could life in a cold shelter be better than life in a home?

Until I tell you that many of the animals surrendered to us have lived with mindless, thoughtless, brainless excuses for humans who have some mysterious misunderstanding of the fact that the dog in their home is a domesticated wolf, complete with a domesticated wolf’s set of specialist killing tools… teeth and claws. Yes, even your shi tzu. Respect for that has usually been sadly lacking.

Add to that all the people who really don’t seem to have been expecting a dog to do, you know, dog stuff. Digging, barking, whining, crying, wanting to be with people, killing kittens, wanting to run, licking their arseholes, eating from dustbins, digging up guinea pig corpses… all par for the course for your usual dog.

That aside, other than momentary explosions behind closed doors, we manage to restrain ourselves pretty well.

You might overhear us having conversations that go like this…

“Well, I wanted to tell him that he should tell his kids the facts of life… Daddy was too stupid to keep the guinea pig away from the dog… the dog killed the guinea pig… now Daddy’s taking the dog to the vet to be killed.”

“That couple that surrendered the labrador on Tuesday? Have you got their address? I need to add them to the black list because they’re now looking for a German Shepherd.”

“That dog that just came into the pound? Was it identified? That’s the dog that came from that farm I was at in June to investigate. Under no circumstances give that dog back to the guy without sterilising it… if he bothers to claim it.”

“Please can you add her to the black list? She’s just picked up two dogs from another shelter, including the five she already has and I’m worried about a hoarding situation.”

And that’s just in our shelter hours!

Some of us come home only have to rein in our tongues on Facebook as well.

With the lady advertising the four-year-old poodle of an 87-year-old neighbour…

With the woman who wants a “cheap” miniature pinscher (or a giveaway if possible)…

With the woman giving away a Malinois puppy…

With the people asking for 50€ for unchipped, unvaccinated labrador-mix puppies…

With the woman who wants a cheap or free French bulldog…

With the woman who says she can’t possibly consider a six-year-old dog, because that dog might die…

With the woman giving away free, unidentified, unvaccinated kittens…

With the person looking for a free puppy…

With the person who says they want a cheap or free puppy because they don’t have loads of money…

With the person who’s lost their six-month old unidentified puppy…

With the person who is pissed off that they have to pay to identify their puppy…

With the person who paid 50€ to identify a kitten and then the kitten disappeared, so they think they wasted 50€…

With the woman who always has four or five kittens to give away each year, but “they’re not her cats”…

With the woman asking for 700€ for her French bulldog puppies… who don’t have pedigree papers…

With the people who never go to shelters but happily post ‘Adopt, don’t Shop’ stickers on everything…

You just have no idea what is going on in their tiny, tiny brains.

Our work at the shelter is quadrupled because of people who have not identified their animals. In 2014, 22 cats were returned to their owners out of the hundreds that passed through our doors. Sure, you may very well lose an identified animal. It may be stolen. It might be expensive. Your dog might never go anywhere without you. But if you don’t identify your cat or dog, be prepared for the fine you’ll get when we pick it up. That’ll be the price of the chip AND vaccines AND a fine for letting the animal stray. And we might also charge you kennel rates too. That’s going to work out a lot more expensive than the amount it cost to identify your animals.

Poverty does limit animal ownership, no doubt about it. If it didn’t, I’d happily keep Effel my foster dog for ever and ever and ever. I’d have kept Mimire and Vanille and Fripouille instead of finding homes for them. I’d have adopted Hagrid and put him in a big pen in the garden that was all to himself. I’d have my full quotient of nine dogs. I’d have whipped Amon and Aster out of the refuge and given them a home. Four is my hard limit, and when Tobby goes, I’ll probably stick to three for a time. Between specialist foods, dental hygiene, bedding, leads, blankets, medicines, vaccinations and regular check-ups, pets are expensive. If you can’t afford a cat or dog, get a gerbil. I had a gerbil. He was great. He was also cheaper to look after. But don’t go on Facebook and ask for a cheap puppy if you don’t have the means to look after it. You certainly won’t have the means to sterilise it. Don’t ask me to get out my violins because you’ve not got the money to own a dog. Most of us would have more animals if we had the means. Yes, being too poor means you shouldn’t own a dog. There, I said it.

Age should also limit animal ownership as well. Who on earth sells a puppy to a senior? Someone actually said that they couldn’t bear it if the animal died before they did the other day. There is something disgustingly selfish about people taking on young animals knowing that they will outlive the animal, that no provision has been made for it after the owner dies and that whoever clears up the estate will become responsible for taking the animal to the shelter. I am always gentle when I say “Do you think this dog is right for you? He’s very young and very strong.” but inside I am furious. What life is it to offer to a young dog? Even poodles need exercise. Really, what I am saying in my head is “selfish selfish selfish selfish selfish” … and that’s just the nice stuff I am saying inside my head. Yes, being too old means you shouldn’t buy a puppy. Glad to get that off my chest.

Your means and lifestyle should also influence your animal ownership too. If you don’t have time, don’t get a dog. Get a cat maybe. Many cats can tolerate a more independent life. Or get a fish. Unless you are dedicated to walking the dog before and after work, and sometimes in lunch-times too, don’t get a dog. Don’t assume that a garden is sufficient exercise for a dog. It’s not. If you want to get a dog and keep it in a room whilst you work, or keep it in a garden pen whilst you go about your daily business, don’t get a dog. Dogs are social creatures and they suffer when we deprive them of companionship. Yes, you are a knob if you expect a husky to be happy with a tiny back yard.

Don’t get me started on the people who feed “feral” cats. First, if they’ll approach you, they’re not feral. They’re people cats. If you feed it, that cat is now your cat. I don’t care if the law makes it your cat after one meal or fifty. Feed it once and you’re encouraging it. Feed it twice and you’re creating a habit. Feed it three times and the cat has certain expectations. If you are feeding it, it’s your job to also ensure its other physical needs are met, including sterilisation. Please don’t give me the “it was starving” line. Unless the cat is too weak to move, it’s not starving. Feed if you like. Trap and take it to the vet if you like. But above all, know that the food you give it has strong implications and that nobody in rescue will pat you on the back and say “Wow! Well done!”. If you feed stray cats and you want gratitude, you’re miaowing to the wrong person. What you are doing, and let’s not mince words about this, is creating and encouraging the baby steps of a giant ownerless kitten community who, given two or three years, will be plagued with diseases and illnesses from interbreeding. Unless you want to end by feeding twenty ill and yucky cats, don’t start feeding one. If you have genuinely found a cat you think is lost, please please call us BEFORE you feed it. Yes, lady, I really do think you wanted to have a pet, not pay for it and wash your hands of any responsibility when the inevitable happens. Don’t tell me you do it for kindness.

And puppies… oh, puppies. First, there’s a law to stop you selling your puppies. No good telling me that the 50€ from each of the puppies will be used to castrate dad. A castration is around 110€ for a big dog. That’s the profit from a couple of puppies. Shelter workers are not stupid. We can do adding up. Or you’ve got another litter due by the end of the year? You’re not a person who has accidents with your dog, you are a feckless breeder who has netted almost 1000€ without paying out. Selling a non-pedigree puppy for 600€? That dog is a mutt. A mutt! Look at the other people selling mutts. They sell for 50€. They shouldn’t, because it’s illegal, but they try. That is the going price for a mutt. A puppy without papers is not an Amstaff or a bulldog, it is a mutt. A mutt who looks like a bulldog or an Amstaff, but a mutt nonetheless. Yes, you are far too money-grubbing to be involved in dog breeding.

And the people who say “Adopt, don’t shop!”. Not every breeder is a back-yard breeder. If nobody took cautions with dogs, there would be more dogs abandoned at the shelter. The simple fact is that indiscriminate breeding leads to Marleys who eat plasterboard, have excessive energy or unmanageable character flaws. Do you think shelter pups are the best option? Sure. I like the idea that pedigrees should be done away with, but the pups that result from accidents, where dad isn’t known… they’re the pups that turn into mastiff crosses rather than boxers, who take “bounce” to the next level. Don’t even get me started on the science of stress for in-utero pups, for inherited fear or aggression, the science behind orphaned puppies and the risk of becoming a reactive, fearful dog as a result. The refuge is not bursting full of pedigree dogs with paperwork who are identified and vaccinated on arrival. That tells you all you need to know about the correlation between breeding and rescue. There isn’t a correlation. The dogs who stay a long time at the refuge are not ones born with papers. They are crazy, unregistered offspring of random dogs, sold for 50€ to people who didn’t bother to get them chipped or vaccinated. If you want to see what orphaned puppies without parents turn out like, I want you to meet my dog Heston. He is super-smart. Just so you know, my whole day is arranged so that he gets the stimulation he needs. The world doesn’t need a thousand Hestons. So what do I really think? I think you should stop being a Facebook warrior and get yourself involved in rescue. Properly. You should understand personality traits that are inherited and how stress affects canine foetuses, the difficulties of raising a dog whose very DNA demands something different. You should understand the uphill battle it can be to adopt a puppy whose parents are not known. Hestons are not for the faint-hearted or the weak of spirit. Be smart. Or be quiet. The last thing we need is to close the dialogue between breeders and rescue.

Rescue dogs are not for everyone. Dogs are not for everyone. Dogs are not really even for most people. You are not entitled to own a dog. It’s not some right you have. If you do own a dog, you owe it to that animal to look after it, to consider life from its perspective, to be respectful of its physical and emotional needs. That’s not to say there aren’t tragic or sad circumstances where people are forced to surrender a dog that they can’t handle through no fault of their own. There will always be dogs who need owners with a skill level that surpasses our own or who need a home which we can’t offer.

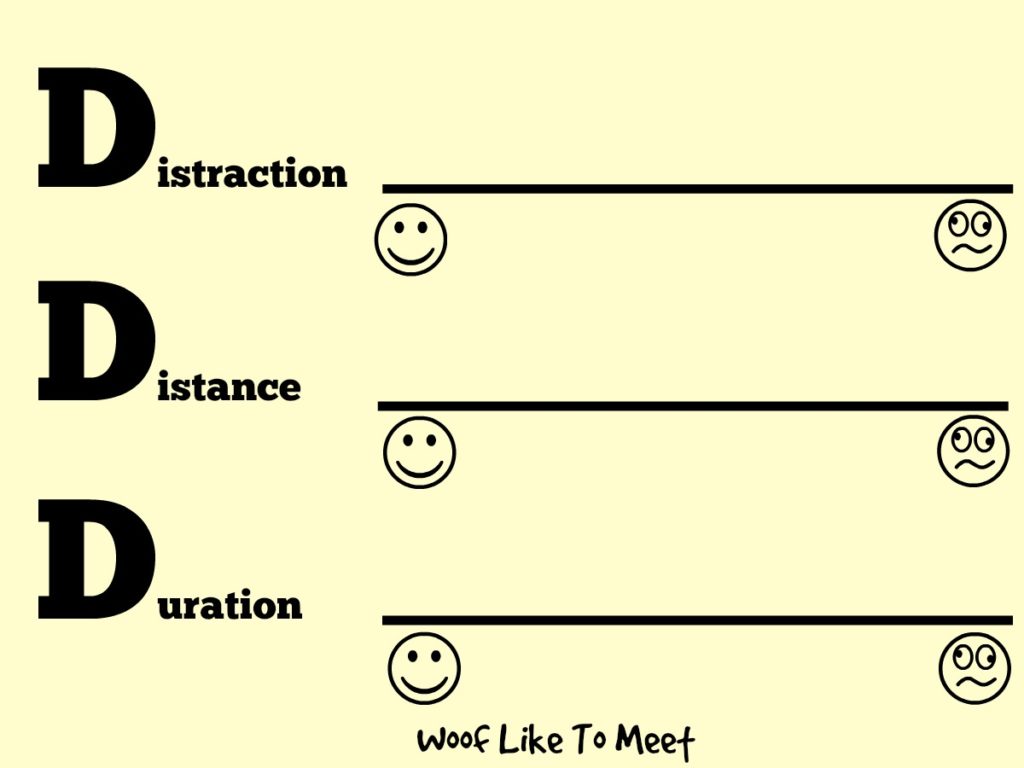

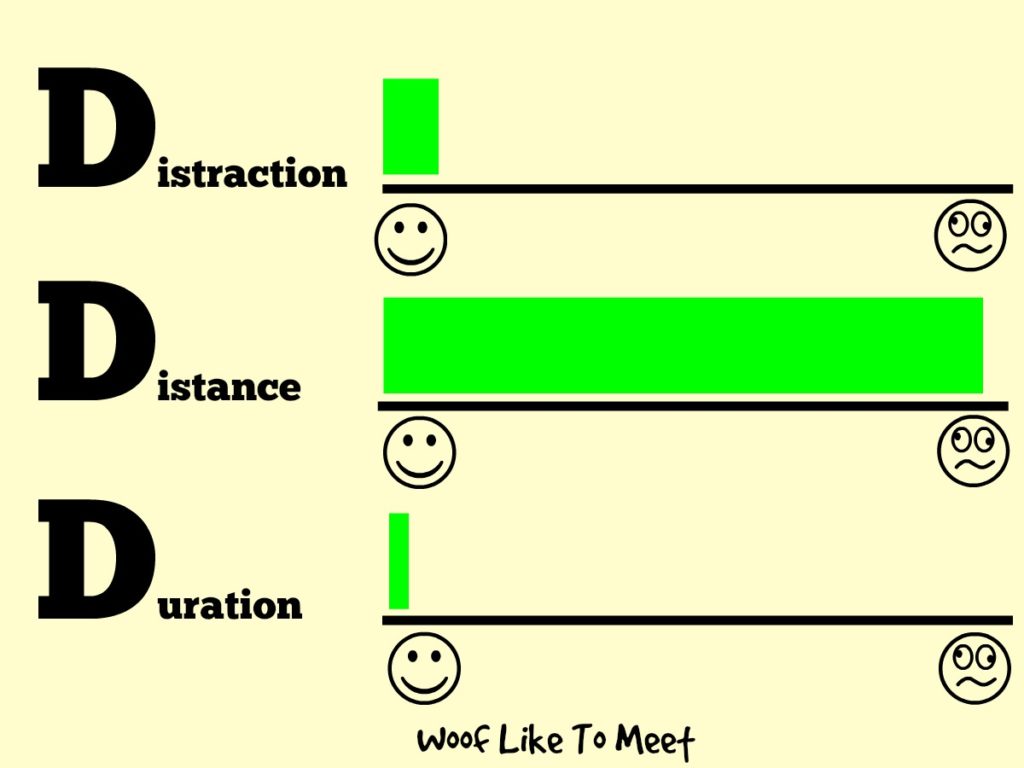

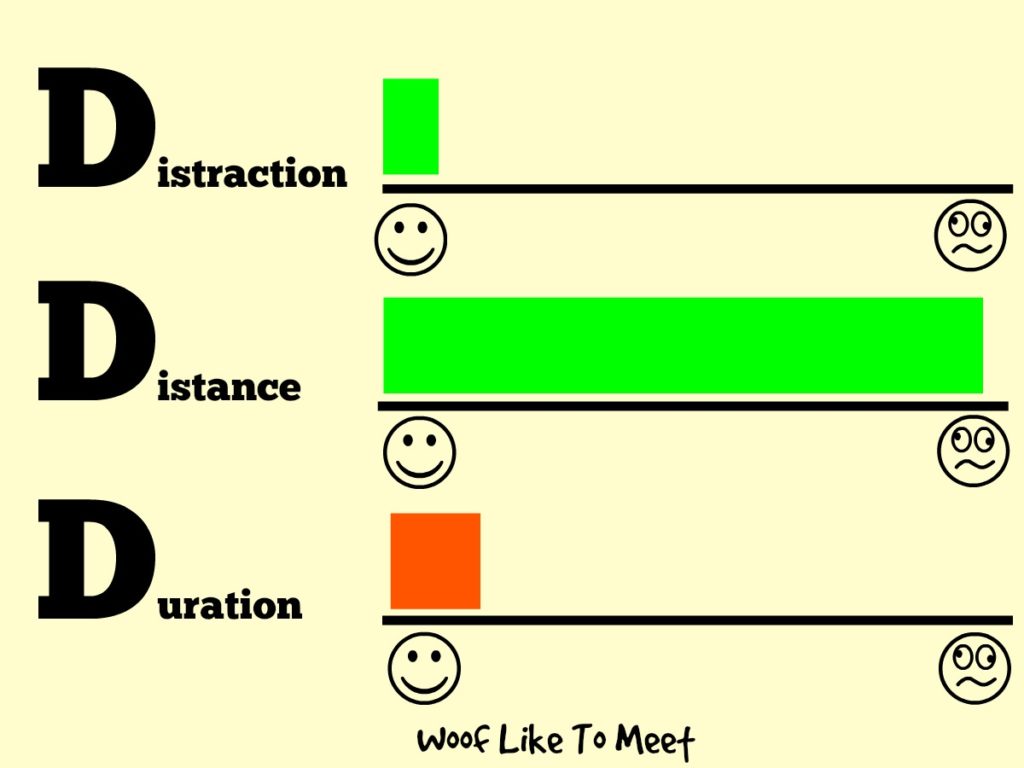

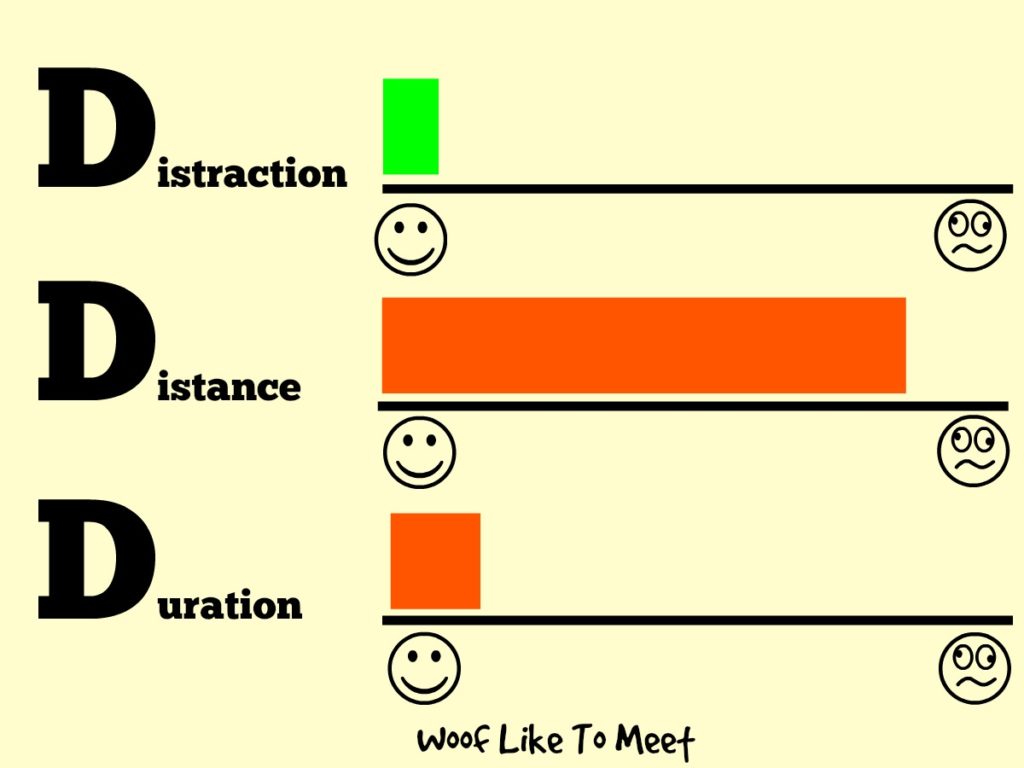

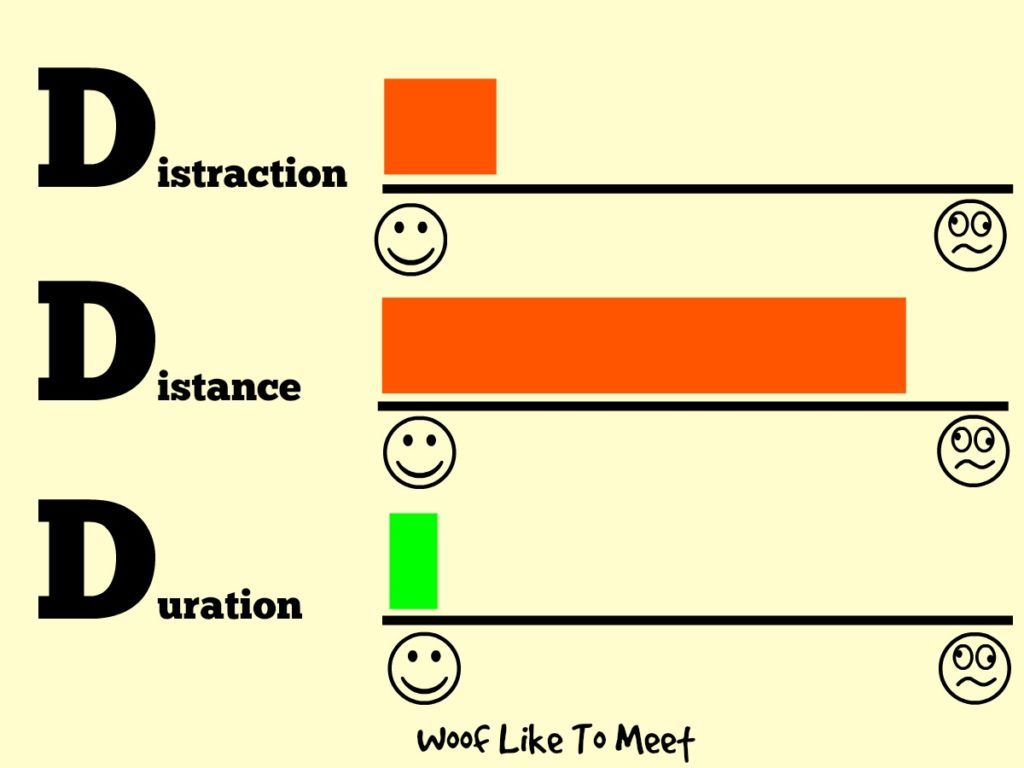

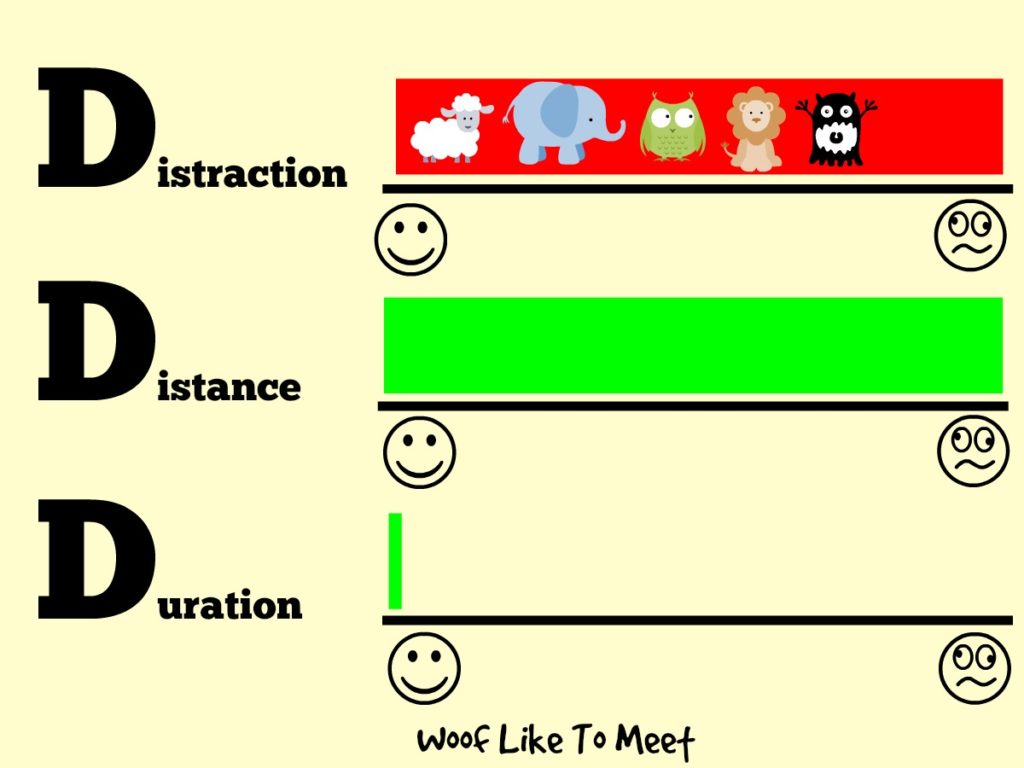

That said, if you live in an apartment and you want a husky, if you live in town and you want a pointer, if you work long hours and you want a shepherd, you are buying into a breed who have basic needs that you are never likely to be able to give it. No wonder so many shelter workers end up all…

and

Luckily, there are plenty of people to keep us from going completely insane, from the foster families who take on a mum and her puppies to the people who come and adopt an ancient German shepherd even though they’d only lost theirs a few weeks ago, or volunteers who bring a packet of biscuits with them as well as a smile.