Fact: it’s not just rescue dogs who can be off into the distance off-leash, but a rescue is perhaps more likely than most to lack this particular dog skill. The sad fact is though that a rescue dog may have the best recall in the world but if he’s a dog whose name or recall signal has changed, you’re likely to have a dog who has either not been given the right recall cue or who never had one in the first place.

And let’s be honest: 80% of our dogs come in via the pound. That’s a lot of strays. It leaves us with a conundrum as well – did the dog have poor recall in the first place and that’s why it’s in the pound? Is there some owner out there still shouting for their dog to come back?

If you’ve picked up a rescue, you could have a dog who had terrible recall in the first place, who’d never been taught, whose original name has been forgotten… there can be any number of reasons why your new rescue would be best to stay on a leash.

But if you’ve got your own dog and you’ve had them since they were a pup, you could have a potential pound dog just biding his time. There are many, many dogs I meet off-leash whose recall is shocking. Their owners are lucky they don’t go missing or they aren’t hit by a car.

Of all the dogs I have had, all of them are potential pound dogs in certain situations. Or proper pound dogs for three of them, picked up as strays. Tobby used to like to toddle off on his own – no surprise how he ended up at the shelter. Ralf liked to go for a wander and desert his guard dog post – and no surprise there either. Amigo is a pound dog whose hunting ways have left him with bullets and a habit of selective deafness where rabbits are involved. Tilly will happily chase cyclists down the road and ignore me if there’s a cow pat to be scoffed. Molly once disappeared into the bushes and wasn’t seen for hours. Heston has either perfect recall or zero recall and once went missing for four hours, and Effel chases Heston wherever he goes.

I’m pretty sure most households are fairly similar. Poor recall is endemic. If you ask me, it’s one of the most frequent problem behaviours.

Three of my current four here have lovely leash manners. Two of them are real homebodies who’d never leave the gates. Two of them are reactive around strangers. Two of them have house-soiling issues – one because he’s on cortisone and the other because she’s a monkey for forgetting. One of them jumps up from time to time. None of them chew anything they shouldn’t anymore. None of them dig (any more!) None of them escape (any more!) None of them bite or fight. But all four of them have poor recall in certain situations. That means it’s the number one issue in the Woof Like To Meet house.

Poor recall is also obvious in several viral videos on Youtube. You’ll remember Fenton, of course.

There is potential for every single dog to have a Fenton moment.

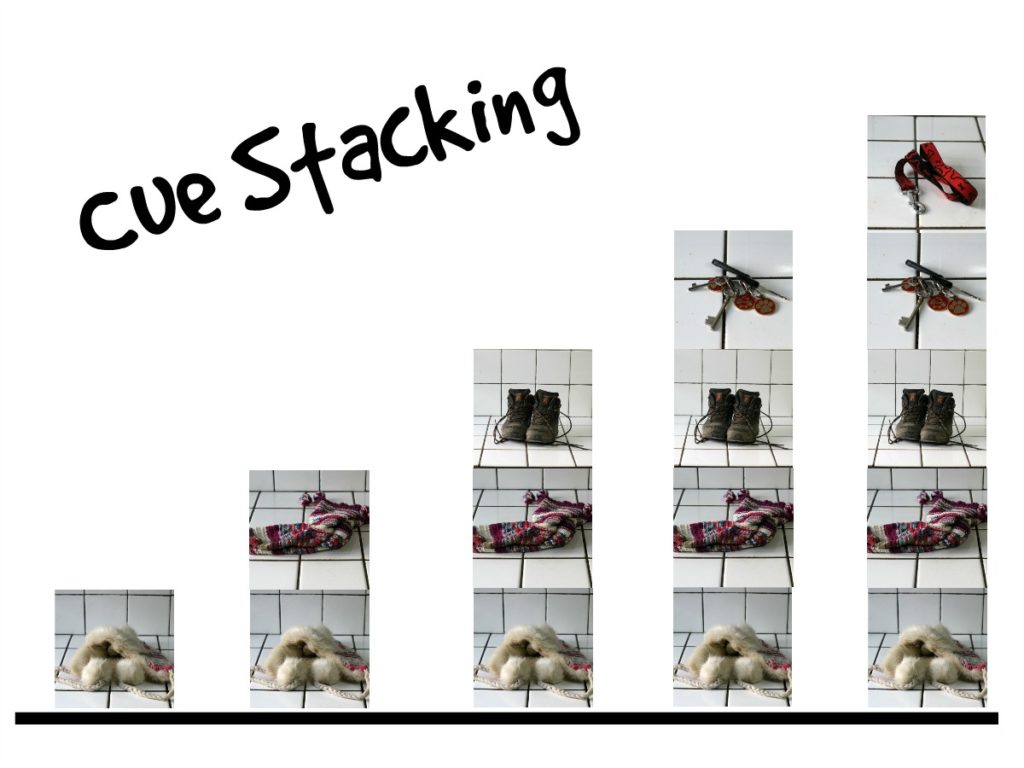

If we remember that recall is largely dependent on situation, you’ll understand that good recall depends on controlling the situation. Sometimes, recall is called “situational recall” for that very reason.

Why do dogs have poor recall? There are a number of reasons. But the main reason number 1 is that it is part-and-parcel of being a dog. What do dogs get out of coming back? A biscuit, some praise maybe. What do they get out of running away? A game of chase. Ten minutes of snouting out some amazing and wonderful smell, wrapped in the delight of a behaviour that is quintessential, hard-wired DOG. Couple that with the chase instinct and you’ve got a tough problem indeed. David Ryan’s very excellent blog post and book will help you if you have a hard-wired chaser. It’s a behaviour that needs more than this post can give you. But it’s not untreatable with dedication and commitment.

If you have a dog, however, who is just a bit haphazard rather rhan a dog who is completely obsessed, then this post is made for you

First you need to know how bad that recall is.

Think you’ve got a dog with poor recall? How poor? Completely zero? Want to put it to the test?

Wait until your dogs are in the house and they’re kind of otherwise occupied, like mine are now. I want you to get up, sneak off and go to a place where treats come from. Mine get home-made peanut butter for pills from the fridge, and occasional bits of meat and treats as I’m preparing Kongs and rewards. The fridge is a treat dispenser extraordinaire in my house. The shelf where I keep the Kongs is also a good bet. And the room where I keep the food.

I want you to sneak off to the spot where you dispense most of your really high-value treats from or the dog’s food and I want you to call your dog. Call them excitedly, like you’ve got something amazing for them. And give them some really amazing contraband from the fridge.

What happened?

Did your dog come? If not, it’s probably not a place with a strong enough appeal or your dog has very poor recall habits. Your dog may also have hearing issues. How long did it take your dogs to come? You can see from this that it took Effel 5 seconds, Heston longer (8 seconds and a second call – he needed the T word to break his usual ‘out of the kitchen’ habits) and Tilly even longer (12 seconds).

I apologise for the blurry low-light video. And you’ll see there’s only three dogs here too. This fridge test was actually a really good test to see how Amigo’s hearing is right now. Not working at all from five metres. He was asleep in the living room.

Now they’re a bit slow on the uptake. I don’t feed them often from the fridge and I’ve never, ever called them to it before. It’s not food time and my dogs (except Tilly) don’t come in the kitchen unless it’s food time. In fact, I’ve trained them to stay out of the kitchen unless I invite them in. I love how they all stand around like, “Put the Treat in the Mouth, lady.”

Now give it five minutes and do it again. Call your dogs.

It took seven seconds to get all of them in the kitchen. Tilly first. The Tilly is smart when it comes to food. That dog will do anything for a biscuit. Effel’s quick because he’s a beauceron shepherd and if you can’t do this with a shepherd, you need to give up straight away. They don’t have ‘personal time’… they have ‘stand-by time’ when they’re awaiting instructions from you. In fact, if you have a shepherd, you’re probably not reading this post unless their recall is poor when out on a walk and they go all “must see off the moving thing”. You’ve probably got bigger problems in the house in not being followed around by your dogs constantly! Heston’s a more independent kind of guy, but even he’s in there super-quick the second time.

If your dog was confused in the first test and took a while to come to you, they won’t be by the second, I guarantee it.

But if after four or five attempts, you’ve still got a non-existent recall, time for the vet’s for a hearing check or a great positive gundog trainer I think!

The good news is that if you’ve got recall with this test, you’ve hope of getting recall in other places too.

There are three factors that make recall good here: you’re close to your dogs, your dogs are inside (and therefore prevented from leaving or being distracted) and you’re asking them a thing that is not difficult. My dogs are all just waiting for their walk or snoozing, so they’re alert and doing nothing else. No real distance. No real difficulty. No real distraction.

I can do other things to reinforce recall as well. Social facilitation (peer-pressure!) is strong with dogs, so if you’ve got a multi-dog household, it’s more likely they’ll all run off after a deer together and ignore you, but it’s also more likely that if you call and one comes running, the others will as well. You could encourage speed among your dogs for recall by having one treat for the dog who gets there first, but that feels a bit mean to me. Dogs are very good at fairness and their obedience drops if another dog is rewarded more than they are. But it could still hone their competitive edge. More research needed on that!

Another thing that changed the difference between the first twelve-second recall and the second five-second recall is habit. The first time, that recall was slow because I don’t make a habit of calling the dogs into the kitchen. The second time it’s become a habit – albeit a two-time habit. I’m going to share a secret. I’m never ever going to call my dogs to the fridge to feed them again as I don’t want to encourage them to the kitchen. I don’t like them in there unless it’s meal-times. But I do use my mantlepiece as a toy/treat and Kong storage facility, so I guarantee I get quick recall if I stand there. Making a habit out of recall is vital to increase speed and reliability.

You should also think about your cue for your dogs to come. It’s worth teaching a new word completely from scratch if you’ve had a lot of recall fails. I use ‘doggies!’ and you want an excited, lively tone. What you want is that word to become associated with most wonderful, amazing, fabulous events. High-pitched, positive, giddy… it’s all good. How fast was your arse on the seat when your mum said “Dinner time?” compared to how slow your arse hits the seat when your teacher said “Spelling test!”. You want the ‘Dinner Time!’ response. No good if your “come!” makes your dog think a spelling test is on the way. If your dinner time has been seven days of sprouts and cabbage, you might be a bit reticent about coming to dinner.

Besides social facilitation and habit, you should also use high-value rewards at the beginning with your dogs. Be mindful that you’ll need to phase them out and have times where you don’t reward them for recall. After ten tries or so, have one or two where you call them and don’t reward them. Give them a fuss by all means, but no food. Variable rewards create a more reliable recall than a reward every time, I promise! You should start phasing them out quite quickly.

With these three things, I bet you can get a reliable, fairly instantaneous recall in the house in less than five tries over a day or so.

Next is the bit that people find hard to understand. Dogs don’t generalise well. When you cue a dog by standing in a regular spot and rewarding fairly regularly for them to come to you, it doesn’t mean they think they should do the same when you move to another spot. So you have to teach them. Time to move spot, improve the quality and reward rate of your rewards and try again. You absolutely need to use your dog’s food allowance for this as well, so stop feeding them from a bowl and make them work for it! See every biscuit in a bowl as a wasted learning opportunity. You’ll even want to space it out over a few hours because otherwise you will end up like the Pied Piper of dogs, with them following you everywhere, I promise you. That’s pretty annoying.

Once you’ve mastered that second spot inside, move again!

Remember… call your dogs (cue), get a behaviour, reward your dogs (and phase out the reward) so that eventually, you’re going from request to response without any need for a reward.

What you want is a 98-100% recall indoors in four or five different spots, over a range of distances and into places your dogs don’t usually go (or don’t like to go… the bathroom being one such place for my dogs!) with a variable reward schedule before you even move it outside. Over 100 trials, you can have a couple of mistakes. But if your mistakes are too regular, you need more work in the house first. You can (and should) also build in distractions in the home, like trying to do this when your dogs all have a bone or a chew. My test is doing it when the post lady’s van pulls up… not 100% there by any means, even in the house. Before you move outside, you need a rock solid recall in the house first. I’d also build in a sit-stay-release response, as you don’t want your dog running off the moment they have the reward. A sit-stay-release response is easy to teach here. Most owners should have a release cue. Mine is “Allez!”. I’d also build in a ‘look at me’ or ‘focus!’ response (Mine is “eyes!”) For me, my cue sequence goes: “Doggies! Sit. Eyes.” and then I give the treat. Then I say “Allez!”. No point giving a break cue and encouraging them to stick around for a reward.

Once your dog can come to their name (or a group name), sit on cue, stay on cue, release on cue and look at you the whole time, you’ve got a great in-house recall. You can even use your body language in there – what I call a ‘rolling recall’ – where you walk off and call your dogs to you. Patricia McConnell in The Other End of the Leash makes a compelling case for dogs interpreting our body’s forward motion. Calling your dogs (because they can’t see you so they need to hear you), turning your whole body to point away from the dogs and walking briskly in the opposite direction is the best signal that your dogs should stop the course they’re on and follow you. I can’t count the number of times this has worked. If I call them and run away from them, not only do I become a great game of ‘Chase!’ in myself, but it’s very clear to the dog that I’m going in the opposite direction. I can’t tell you what a life-saver this technique is when I see a deer appear out of nowhere, or another off-leash dog, and I don’t want my dogs to see it and give chase. Starting this in-house can help it become a really reliable device to get good recall at critical points. I’d also include a few collar-grabs in there, since outside many dogs end up getting their collar grabbed as a consequence of a recall (or having their leash put on!) and who’d come back if you’re going to have your collar grabbed? The ONLY consequence for recall should be positive. But as soon as my dogs come towards me, I can practise the collar touch and reward them for it too, so they are used to it – and they don’t end up being one of those dogs who dance just out of reach and abscond when you really need them not to.

I can’t stress one thing enough though. The ONLY consequence a dog should have for coming back to you is the most amazing love and fuss. Like you have been apart for months and months. But building in a collar grab practice can prevent a bite or any resentment that a dog might feel for coming to you rather than going off doing their own thing.

When you are absolutely sure that your dog’s recall in-house is rock solid, even with distractions and definitely without bribes, you are ready to level up!

You can move outside into a quiet, safe space. That might be your garden. But if you have a noisy garden or live in apartments, a quiet spot in a park can also work. I’d keep your dog on a long leash first and here’s where you really, really will need a sit-stay-focus-release cue. The leash here is acting as your walls, and only when you can get a reliable sit-stay-focus outside can you even think of moving up to testing with a longer leash and bigger distances. I use a 3m leash then a 10m, then a 20m. I’ll do a few positional requests, like ‘sit-focus-down-stand-sit-stand-down’ and build in the ‘stay’ before using my new (and proofed!) command, ‘doggies!’ or whatever it is I’m using as my cue word. Then when it’s good at 20m, I’ll take the dog off-leash to try it. And at this point, I am going to have some of the best, most wonderful, most stinky rewards. I want that first time off-leash to be THE BEST-EVER MOST WONDERFUL recall. I’ll do it when the place is completely and totally distraction-free. No cats. No squirrels. No squawky magpies. No passing traffic. No noisy neighbours. I’ll then increase the distance too.

After, I’m going to build in some distractions, too, just as I did in the house. From chews to toys to a game of Sprinkles, and I’m going to try recall there as well. And only when I have 98%-100% recall in the garden on and off-leash, with and without rewards am I going to take it beyond this safe, walled outside space.

My emergency garden recall, by the way, is to run away, off up the garden as fast as I can, shouting “Whooo! tea time!” and heading to the food cupboard. This worked perfectly with a guardy terrier who’d stolen my shoe and run off down the garden hoping for a good game of chase. I even got the shoe back. ‘Tea time!’ is my twice-a-day failsafe excitement word that always, but always gets 100% attention. It only works if you have a food cupboard to hand though.

The technique of turning away to encourage recall is a great one to inspire your dog to follow you. You can find more details and more tips in this article on the Whole Dog Journal website.

Once you’ve got good in-house and in-garden recall… time to level up.

You know how it goes. Out of the garden, no-distraction environment, on-leash. Sit-focus-down-focus-stand-stay repetitions out there in the big, old world. Fantastic treats, high-ratio of reward. Then a longer leash. Then one that’s longer still. Then build in distractions. If it gets too hard, take it back to the last known rock solid place and make the distractions or distance less difficult. If I can’t get good recall on a 20m leash in an open field, I’ll try with a 5m leash. If that’s too hard, I’m going to maybe take it back inside the gates, or wait until I’m on a walk and I can see my dog is paying attention, giving me lots of eye contact. I’m going to borrow my friend’s secure garden and try it there. Or a tennis-court. Basically, if it too hard to get reliable recall out in the world, I’ll try to manage the environment better so it’s less distracting. If I’m really going to struggle at this point, David Ryan’s “Stop!” programme that I mentioned before is a real life-saver.

When… and only when… I have reliable recall on a 20 or 50 metre leash, I’ll take the leash off. I’m going to do it in a really distraction-free area on a day when I have been practising on-leash recall and I’ve got an excellent response rate without rewards. I’ll bring out my best rewards and that dog is going to think he has won the lottery when he comes back to me. I’m not going to try more than one or two times that first day and I’m going to up the level of challenge so slowly that my dog is never going to have a Fenton moment. If he does… I’m not going to stress it. A Fenton is not coming back until he’s done what needs doing, believe me. My aim is to avoid Fenton Moment Potential.

In fact, if I am ever in Fenton Moment Potential situations, I am going to keep the leash on. Period. You know yourself what distractions are too much for your dog. You know better than anything what causes recall fail. You’re reading this post after all, and you know better than anyone if it’s rabbits or hare, boar or buffalo. I suggest you make a list of Fenton Situations for your dog and you never, ever let your dog off-leash in those situations if you want them to come back. For my dogs, that list is this:

Heston: swallows, crows (less than 20m), pheasant, squawking jays, magpies, hare (but not rabbit over 50m away) deer (within 2 hours and 20 metres of walking zone) other dogs, puddles, rivers, streams, lakes, boar, starey cows, people, walkers, cyclists, joggers, hunters, hunt dogs. Heston has great situational recall in very familiar empty spaces with no wildlife. He is reliable with cows, horses and rabbits.

Tilly: cowpats, other dogs, cyclists, joggers, hikers, rubbish bags, food waste, pheasant, stinky manure

Amigo: is deaf now. No recall at all, bless him. Used to be rabbits or boar and cow pats.

Effel: everything but Heston running or other dogs leaving the pack, which he likes to herd up and move on. Also has a roving eye for orienting towards moving objects when he’s over-stimulated.

You can, of course, build in recall-proofing with leashes and then without, gradually decreasing the distance between you and a cause of poor recall. I did this with cows, horses and rabbits for Heston and we’re working on him not racing off to dive in the water. But generally speaking, if your dog is unreliable around certain stimuli, keep the leash on and go right back to recall basics around that situation.

Remember that even the mildest aversion can be a massive deterrent. A bit of rain and my dogs think they’re made of sugar…

The day Effel’s rock solid recall fails is indeed the day that it is heaving it down. Remember, recall fails happen to everyone, and if you are in any doubt the recall will fail (I had no doubt at all that my dogs would not venture into the rain!) don’t expect your dog to follow you.

Recall, then, is only as good as your environment. Managing the environment for a dog with poor recall is absolutely vital. The predatory motor pattern sequence that comes part and parcel of your dog’s genes means that unless you have a dog with a genetically-inhibited sequence (so livestock guarding breeds) you are likely to have a living, breathing dog. If you have a hound or a terrier, you will no doubt have moments where the Call of the Wild will take over. That’s what leashes are for. Even if you have a rather jolly labrador, you might want to stick a leash on as well.

And… if you’re having problems walking your dog on leash, try this post from last week!

Next week… jumping up.