There’s one thing I’m absolutely adamant about, and that’s not letting unknown people feed fearful dogs. So often, I hear from clients that they’ve got a dog who’s a little skittish around people and they’ve encouraged those people to give food to the dog in the hopes that this will help. These dogs are ‘Stranger Danger’ dogs. They’ve a heightened sense of suspicion over who’s friendly and who’s not. The kind of dogs people say, ‘Oh he’s lovely when he gets to know you.’

Let’s not be encouraging strangers to feed our Stranger Danger Dogs.

There are several flaws in the scenario where strangers hand over treats to your dog. The first being if the dog is genuinely fearful, then food won’t be the first thing on their mind. Imagine the well-meaning but kind of scary stranger as being a walker from The Walking Dead.

Do you feel like taking a cupcake off this guy?

Start imagining your dog sees strangers as zombies and you’ll understand why some dogs really don’t feel like taking a biscuit from him.

And you went better than cheap floury biscuits and asked the stranger to hand over some bits of ham or cheese? Maybe you’ve gone down the route of making it more tempting?

Ok.

If your dog is refusing, that’d be the same as me refusing a block of my very favourite chocolate. That tells you just how scared your dog is.

And if your dog won’t take food from you (let alone a zombie) when the scary humans are around, that tells you something too.

It tells you that your dog is in way over their head and eating is not the first thing on your mind when you’re in fight-or-flight mode.

The person may be the most well-meaning person in the whole wide world. We’ve seen Wicked. We know that Elphaba isn’t a wicked witch, not really. That makes no difference to your dog. No amount of reasoning with them will help them understand that the Wicked Witch Ain’t Really That Wicked.

Your dog is in charge of deciding who they trust or don’t. And if they say they don’t, we’ve got to respect that.

We don’t have to live with it, as you’ll see shortly.

But we’ve got to respect it.

So what if your dog IS taking food from the zombie? From the Wicked Witch? After all, some dogs do.

Sometimes, if the dog is able to, you might see the smash-and-grab.

They dash in quickly, grab the food, sometimes a finger or two in their haste, and only if the food is offered at arm’s length, and retreat to a safe place to eat it. They’re only likely to go in again if food is offered again.

The problem with this is both practical and ethical. On a practical level, your dog isn’t actually learning that the scary human is any less scary, just that they give out cheese from time to time. She’s still the Wicked Witch, just this time she’s got cheese.

On an ethical level, the use of food is forcing your dog into situations they wouldn’t choose to be in simply to get something they really, really want. And that’s coercion. Using food doesn’t make you into a great trainer, a great person or even someone who is innately kind or using force-free methods.

Other people use a lead, a tether or a small space to make sure their dog can’t smash, grab and retreat. This method is known as flooding. You can read more about flooding here and I encourage you to do so if you think it might work. Needs must, from time to time – I’m perfectly aware that when I take Lidy to the vet, I need to use two leads and a muzzle and take a whole pot of paté in with us and even though we manage it with a tucked tail, a few sideways glances and a little growl, I’m absolutely not under any illusion that without the muzzle, the leads and the paté, she’d turn into some kind of Hail-Fellow-Well-Met super-social setter. We’re working on it and I hope one day I won’t have to flood her so that she has no option than to just tolerate it, but inoculations and vet checks are different and they’re her zombie and Wicked Witch Final Boss level in this game called Life, I know that. Just because you’re alright with one zombie doesn’t mean you’re okay with a horde of them – even if they are behind a desk

I simply cannot tell you how many dogs I’ve worked with in the last five years who’ve bitten someone in these circumstances. First time bites – perhaps only-time bites. This well-meant scenario puts dogs’ lives in the balance and runs the risk of some serious medical interventions.

The dog is restrained or trapped. The dog has had to face a number of scary things all at the same time. The dog has thrown out a number of stress signals – lip licks, head turns, shoulder turns, indirect glances, yawns – and they’ve all gone unrecognised by the human approaching them (yes, that includes vets and vet staff!) and then the dog has bitten.

And yet we do exactly this when we put our dog on a lead and ask strangers to feed them. Put the dog up close and personal with their scary stuff and hope that food will be enough to make them feel better.

Now it’s well meant, I know. It’s not a criticism of people’s intentions. Food can change our feelings about things. My own feelings about my lovely grandmother are deeply enmeshed in the fact she is a feeder. Visiting her meant accepting a very large number of snacks, probably at least a pile of sandwiches that could feed twenty people, at least a bit of cake, if not two. Diets died on her doorstep. Willpower crumbled before her. She is cherry cake and lemon cake and salmon sandwiches and petits-fours and M&S crisps and pickled onions and pork pies and Branston pickle and huge chunks of cheese. Food is deeply enmeshed in everything I love about her.

But taking chocolate from zombies is not going to turn them into my grandmother. The Wicked Witch rocking up with a platter of pickled flying monkey brains does not turn her into Elphaba.

Besides the ethics of using food to do this and the practical issues of having a dog start refusing food, there are other issues. Not least the fact that food is a magnet that draws the dog into the space with the human. If you’ve got a smash-and-grabber, hooray. At least they can retreat. But if you’ve got a lingerer, all this means is a highly ambivalent dog is going to end up in the space of a person they don’t like very much for much longer than they would without the food – and when the food runs out and the dog realises they’re a lot closer to the person than they’re happy with, that’s when we can see some nasty bites too. I’ve already had to deal with the fallout of dogs whose food has run out three times this year. If your dog is new to your home, I cannot stress enough the risks of strangers handing food to your dog.

Refusing food from strangers, then, is really not the worst thing your dog can do.

Please do not flood this post with comments about how you’ve used food with hundreds of Stranger Danger adult rescue dogs and they’ve all been fine. I know. We use food liberally at the shelter. I use food liberally with dogs who don’t like me very much and think I’m a zombie. But I know when to do it and how to do it. There are ways and means. And I don’t do this with dogs who have guardians with them. If there is a guardian, it’s their job to dispense the food – not mine. Very occasionally, I might add a bit of food but I hate doing this. I’m very, very aware of all the fallout I’ve just taken you through and I do so with much reluctance – normally because needs must and the owner needs to go faster than I feel like we should. Life is not easy and sometimes needs must. The problem with proliferating liberal advice that strangers should give dogs food is that it is then implemented by people who aren’t aware of the fallout and it ends very badly.

Another part of the problem is that the people who often suggest this are actually not that dog-savvy. Do you know the best place I know of for a dog with a high level of Stranger Danger? People who work with dogs all day long and who know that dogs don’t want strangers waggling fat fingers in their face, who let the dog choose. People who don’t interact with the dog until the dog is okay, who don’t approach the dog, and who are really not that interested in the dog. I’d rather be in a crowd of people who aren’t that fussed about dogs than people who claim they love dogs or that ‘all dogs love them’ – they tend to be all kinds of crazy inappropriate. I know because I am that dog lover who has to consciously myself look at the human, not their dog. I’m crazy inappropriate and I battle it every day.

So what should you do?

The first is that YOU are there with the dog. YOU feed them.

If your dog won’t accept food because you’re too near to the scary zombie, back off to a point where they are able to accept food. Yes, that might be 500m. So be it. You may also need to read my next post about dogs who ‘aren’t treat oriented’ if you’ve got some other stumbling blocks.

You might also need to skill up where your training is concerned.

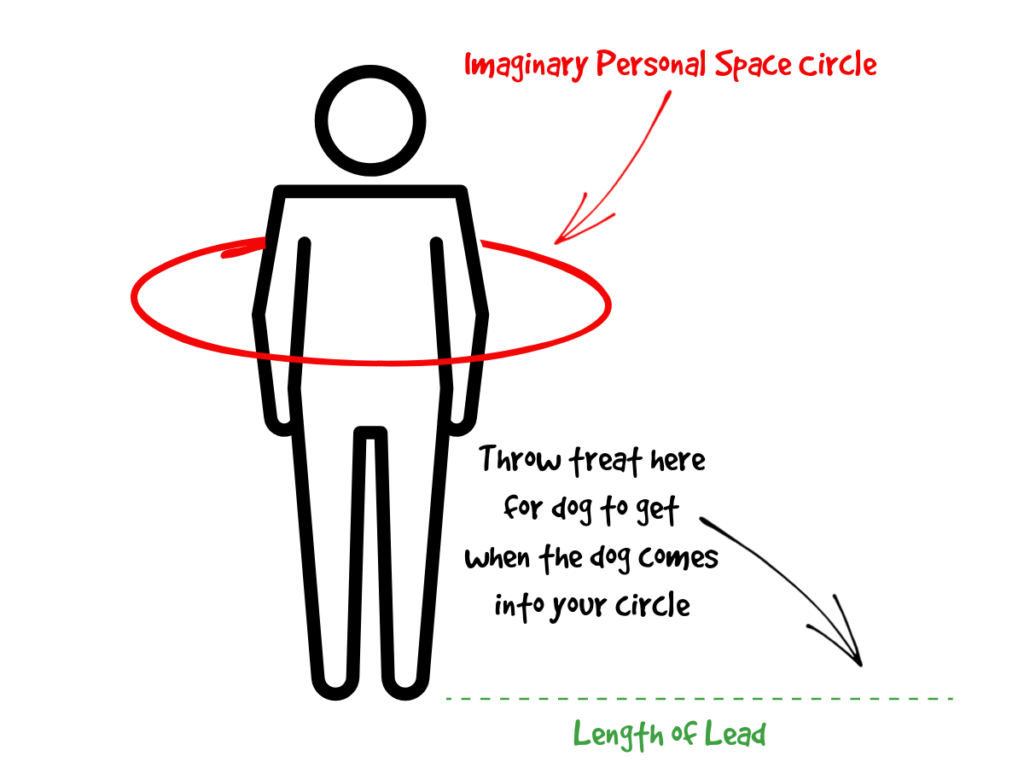

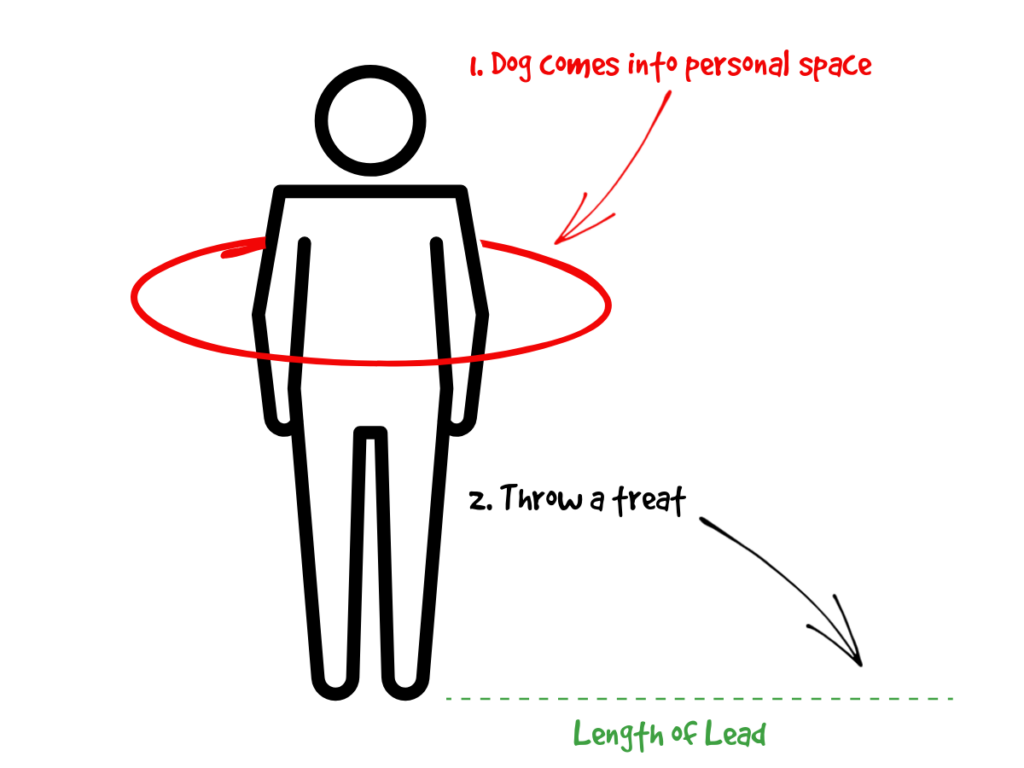

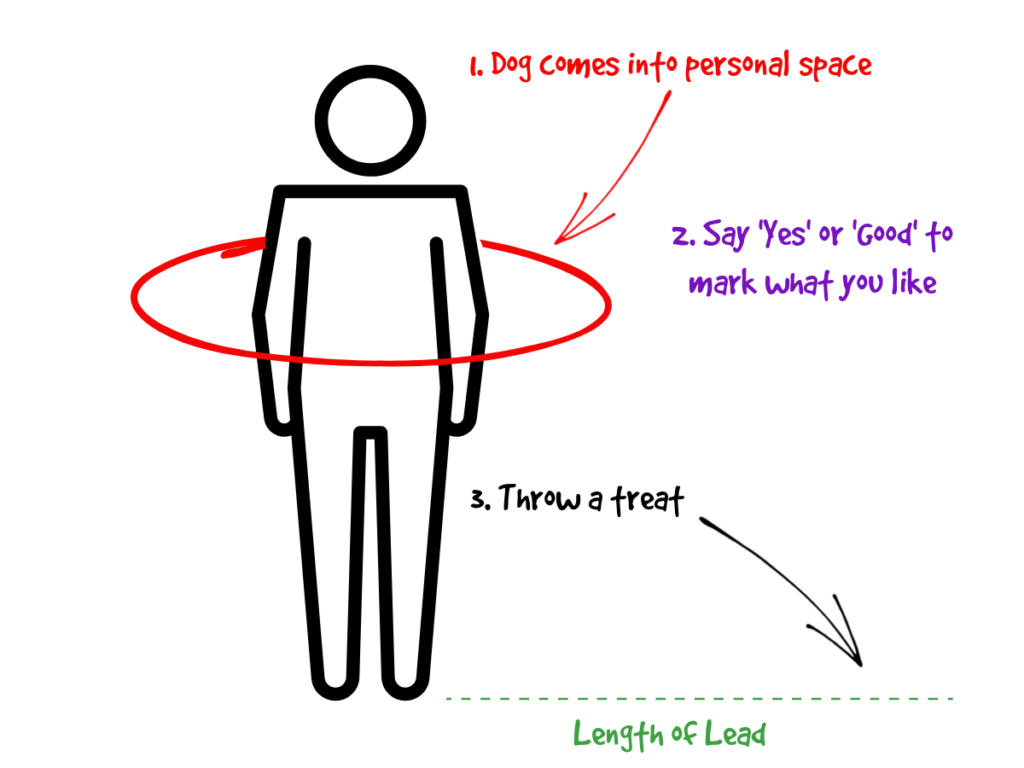

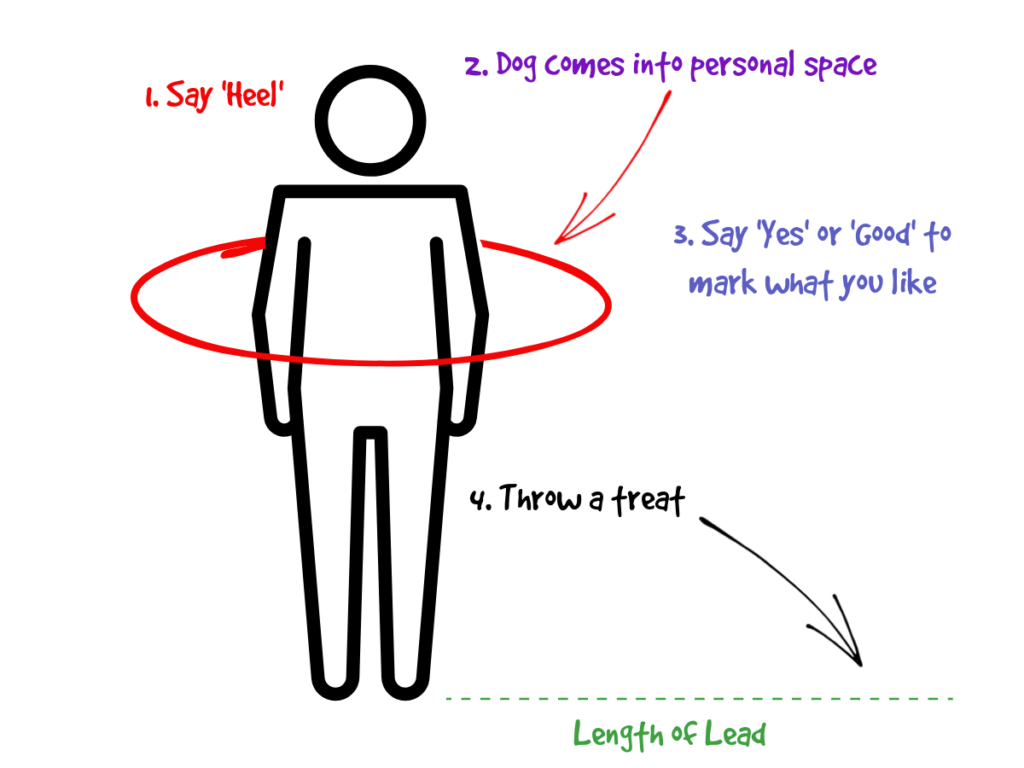

There is a marvellous protocol from Suzanne Clothier called ‘Treat-and-Retreat’ which uses food in ways that encourages dogs to be confident. Find a trainer who can show you how to do a treat-and-retreat protocol, and get good at it.

Or, drop the food altogether. Some trainers like Grisha Stewart use minimal food in their training programmes like Behaviour Adjustment Training (BAT 2.0) and allow the dog to desensitise to scary stuff without adding food into the mix. Other trainers like Sarah Stremming and Leslie McDevitt use food for training in ever-closer proximity to the scary stuff as if to say, “Yes, there are scary zombies just there, I know, but you and I are engaged in some predictable, fun and highly rewarding stuff and you don’t need to be bothered by them. They won’t hurt you and I won’t let them. We’re doing our own thing.”

And this works wonderfully too.

But the food and rewards come from you. Not the stranger.

So with my Stranger Danger boy Heston, what made the most difference?

Allowing him to go and investigate safe people and then come back to me. I don’t use food. He’s anxious, not hungry. I tell him he’s a good boy and I pet him. I tell him how brave he is. I reassure him and allow him to go at his own pace. When he’s ready, those safe people might pet him too. And he just loves that now. He does take biscuits from people but to be honest, I’d rather he approached them on their own merit. I say this with the heavy irony of being the kind of person who always has dog biscuits on her person and who hands them out liberally.

My other Stranger Danger Dog Lidy is different. She likes structure and predictability. She’s not the kind of dog to investigate. I use food with her as it helps me set up a very structured programme for her.

What your dog needs will be dependent on their needs and their past experiences and their past behaviour. There’s no one-size-fits-all treatment programme for them.

So can you use food with your dog who is afraid of strangers? Absolutely – if it comes from you. And it will depend. It will depend on your dog. It will depend on you. It will depend on the circumstances. It’s nuanced and individualised.

Stranger Danger Dogs need a programme that is right for them with exercises and approaches specifically designed for them. What they don’t need is blanket advice about strangers giving them food – or, worse – throwing the food to them. Unless they’ve got the softest underarm pitch and the most perfect placement, they’re unlikely to be able to throw food in a way that won’t resemble a zombie lobbing a grenade to your dog.

Can Stranger Danger Dogs get over it?

Sure. Heston was very happy to walk through a bunch of soldiers on manoeuvres in the forest yesterday. He didn’t even care they were there. They might as well have been very uninteresting trees. Lidy, not so much. I could pretend she didn’t go into stalk mode and that this didn’t alarm me. We did a few reps of our favourite games and we took our time. I listened to her until she was ready to move on without looking like an Apex Predator sourcing her lunch and she remembered we don’t eat people these days. But by the time we got to the soldiers and their lunches, we walked past as if they weren’t luncheon meat in camouflage at all. Heston said hi. Lidy did not say hi. She stood and glowered a little in the corner like Hannibal Lector in a hockey mask.

What didn’t happen, though, was I didn’t ask those soldiers to hand-feed sausages to my dogs, because even though Heston sees those zombies as people these days, he doesn’t need them to feed him sausages. I gave Lidy some snacks because she was a Very Good Girl to face her zombie foes and it was just another episode in our life-long training programme in which Lidy Encounters Zombies and the Zombies Are Not So Bad After All. No zombies looked at her like they might like to pet her. One day, scary zombies will be the exception rather than the rule, I hope, just as they are with Heston. One day, she’ll realise people are Elphaba not the Wicked Witch. Right now, only she decides when people are okay, and that’s fine. At the moment, we’re at that point in Walking Dead where we’re learning to walk among them without them wanting to grab us and without us needing to kill them. We’re getting good at that. And if any zombie tries to grab her or offer her cake, my job is to say, ‘Not today, thanks! We have cake of our own!’ and to step in rather than letting her have to cope with grabby, cake-offering zombies.

But we didn’t get here by strangers giving dogs treats, by flooding my dogs or by using food when my dogs are clearly telling me the scary stranger is just a zombie in a human disguise. Make sure you’re not setting your dog up to fail and don’t fall for this well-meant but ultimately unhelpful advice.