In a previous post, I explored barrier frustration and barrier aggression so that you could get to grips with why your dog becomes a barking furball of craziness whenever they see another dog if they’re unable to get to them. Today, I’m only focusing on dogs who’d like to greet (not eat) another animal, particularly those dogs who can’t seem to handle it when they can’t go running up to say hi. You know, like the black dog in the photo above.

You know these dogs. I’m sure one or two of you own them!

These are the dogs who go nuts when they see another dog. You know, you’re blithely walking along and suddenly your Bernese Mountain dog almost pulls you off your feet. Just as you grab the lead in time, they’re barking like maniacs, pulling, frenzied and drooling.

“Sorry!” you shout and you make a mental list of another place you just can’t take your dog.

Or you know that your dog is 99% friendly, but they’re big and strong, plus they look like Cujo on steroids when you’ve got the lead on them and they see another animal. So you just let them off lead because it’s easier than trying to hold on to them, it’s less embarrassing and most of the time it works out, even if the other dog (cat, horse, cow … add the animal of your choice!)

You know these dogs. I’m sure you’ve seen a car with a frantic maniac of fur barking in the back seat, practically eating the window to get out and say hi.

I’m not, by the way, talking about dogs who want to chase or attack other animals. They just want to say hi!

It always makes me laugh as I remember seeing another trainer’s video of her doing great work in a busy park with her spaniel, then along comes a huge German shepherd, off lead of course, followed by a plump Northern lady. “Don’t worry!” she says. “He’s friendly. He just wants to say hi!”

My worst nightmare.

You see, i know why that lady had her dog off lead… because he’ll have been too strong on it and too frustrated if he didn’t get to gallop up to every other dog in the whole wide world and “say hi!”

So instead, she lets him do what he wants, regardless of whether that’s acceptable to other dogs. For my three that’ll depend. Flika is whimsical. If she thinks you’re polite, she’s fine. Heston is a bit full on Tarzan but he’s a sticking plaster dog himself (rip it off and get it over with kind of greetings). Lidy will bite your dog in the face without even checking to see if he’s a real dog or not first. We’re working on it. Quite clearly, i am a responsible person and she’s muzzled in public and never off lead, but let’s be clear – in those situations, SHE’s not the one doing the bad stuff.

Greeting every single other dog is a bad habit. It’s false ‘dogness’. Dogs literally don’t do this in street groups or in village groups. They don’t do it when working. Guide dogs don’t do it. Search-and-Rescue dogs don’t clock off to say hi to a Pomeranian over the hill. Your trusty Grand Pyrenees doesn’t desert his sheep brethren to go say hi to the collie on the next farm. We encourage it, in my opinion, with puppy socialisation, where we teach young dogs that you get to meet 100% of the dogs you see and 100% of the time it’ll be super cool good fun. We encourage it with our ‘say hi!’ behaviour and our innate desire to socialise with other dog people (and more importantly, their dogs). We do it because we’re all Ricky Gervais at heart and we all think dogs in our community are as much ‘our’ dogs as their owners. We make a bee-line for dogs when we’re dog people because we’re all slightly nuts. I mean, if you’ve ever seen me with a strange Belgian shepherd you know I have to practically blindfold myself not to ogle them, go in for a massive cuddle and end up giving them a kiss on their great, bemused, nose. You know, that bit right above their great, bemused bitey old mouth.

Let’s face it. Dogs, like humans, are a social species. In fact, few species (any?) are more social than humans. Yet do we go down the street kissing everyone we meet? Saying hi to everyone? If a strange bloke said ‘hi’ to me in passing, I might get the Mace out. If he slipped me the tongue, you’d need to muzzle me, let alone my dog.

Yet this is what I think we’ve taught our dogs to do. We teach them “hey dude, you get to meet hundreds of dogs, stick your nose up their arse, maybe hump them a bit, chase them round and round, it’s going to be great.” We go on social walkies and we “socialise” them and we take them to our friends’ houses or dog parks.

And then we go to a park and WE know that our dogs won’t be welcome to do that so we try to put them on the lead and our dog goes bananas.

You see, THEY don’t understand the rules. They don’t know that in real life, you don’t get to say hi to 100% of dogs. In fact, you probably won’t say hi to any dogs. Sometimes, I’m going to take you to the vet, and I’m going to make a decision that the pointer in the corner might not like to say hi, so I’m going to sit with you and ask you not to engage with a dog 2m away. You might be in a room with 10 other dogs and not be allowed to say hi to any of them. Just like people on the morning train, you’re going to be sandwiched in and I’m going to expect you not to acknowledge any of them, especially the one who smells of pee and seems to be in the middle of some kind of mental breakdown.

And that goes for cats, horses and cows too, dude.

Teaching a dog who thinks it’s 100% respectable to say hi to every moving thing is not easy if they’ve not grasped that fundamental concept that most of the moving beings that we will see, we not only don’t have the right to say hi to, we don’t need to say hi to them either. A dog who feels the need to say hi to every other thing with a nose is a dog with a pathological behaviour that is going to spill out in frustration. Hence the low level whining that turns into a bark (reminds me of a time I was observing a lesson in school and one 16 year old lumpen teenage ne’er-do-well spent most of the lesson trying to attract the attention of his friend, a certain Mr Gibbons, by whispering “Gibbons… Gibbons… Gibbons…” in a crescendo, not understanding that Mr Gibbons could see I had my beady eye on the pair of them) Low level whispering that turned into coughs and other big behaviours to attract attention… just like our dogs do. The lumpen teenager knew full well it was inappropriate to have a conversation across the class with your mate but dogs don’t understand those strange social and cultural customs we do.

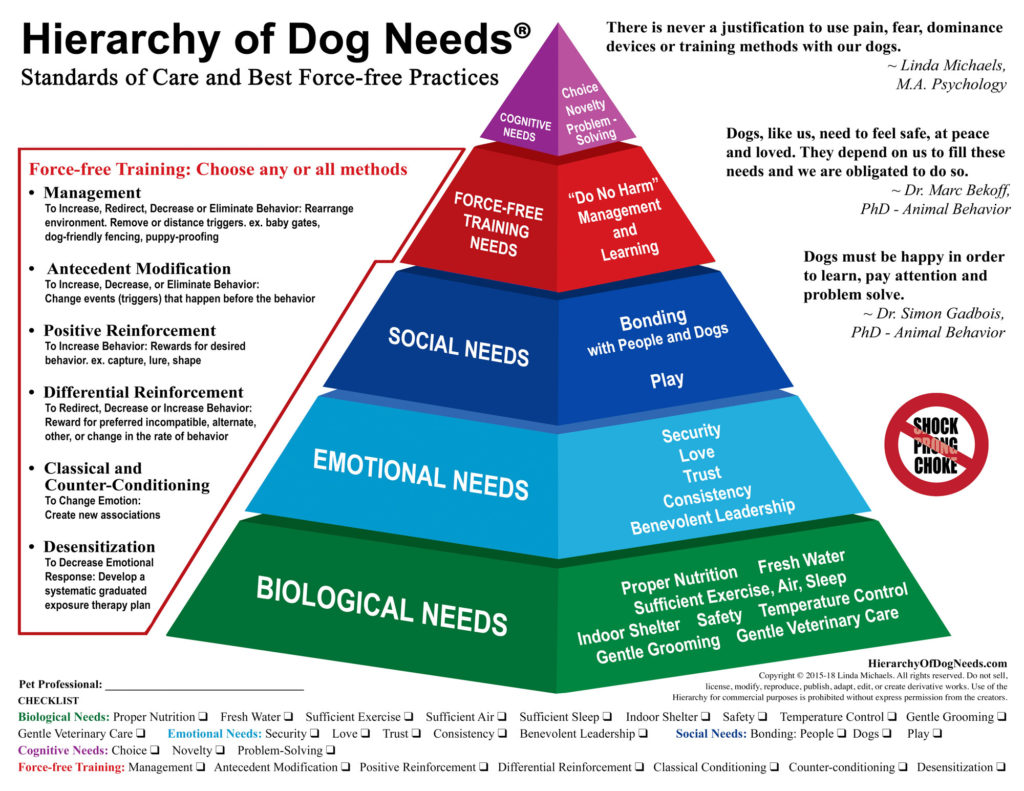

What you need is two-fold. The first is to teach your dog how to cope with frustration. Like toddlers, some dogs don’t understand how to cope with frustration. Teaching concepts like patience, disengagement and tenacity are really useful. Food toys, games like flirt poles, programmes like Leslie McDevitt’s Control Unleashed, Fenzi Academy focus games and all manner of other great programmes can help you with that.

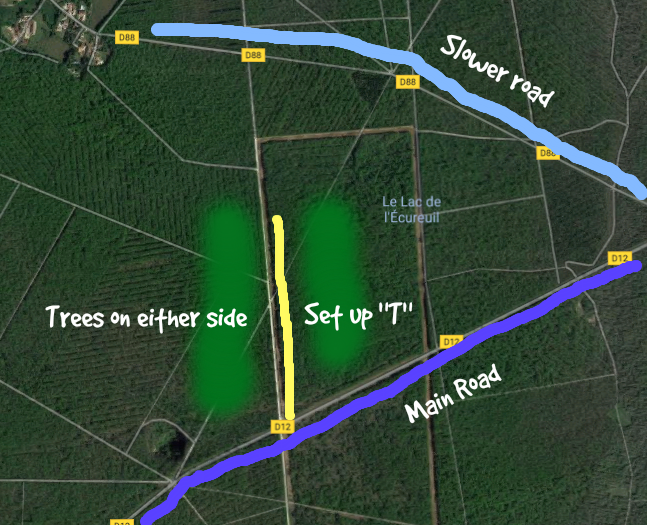

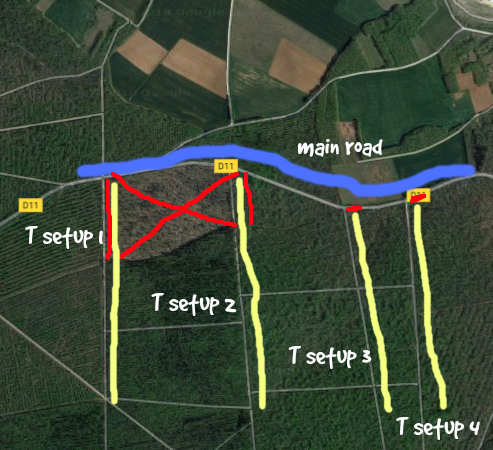

The second thing is a carefully planned habituation and gradual desensitisation programme. This is where you make a plan like the one I did here about chasing and you work through set-ups to prepare your dog to cope. In the meantime, no more dogs/cats/horses/goats until you’re ready.

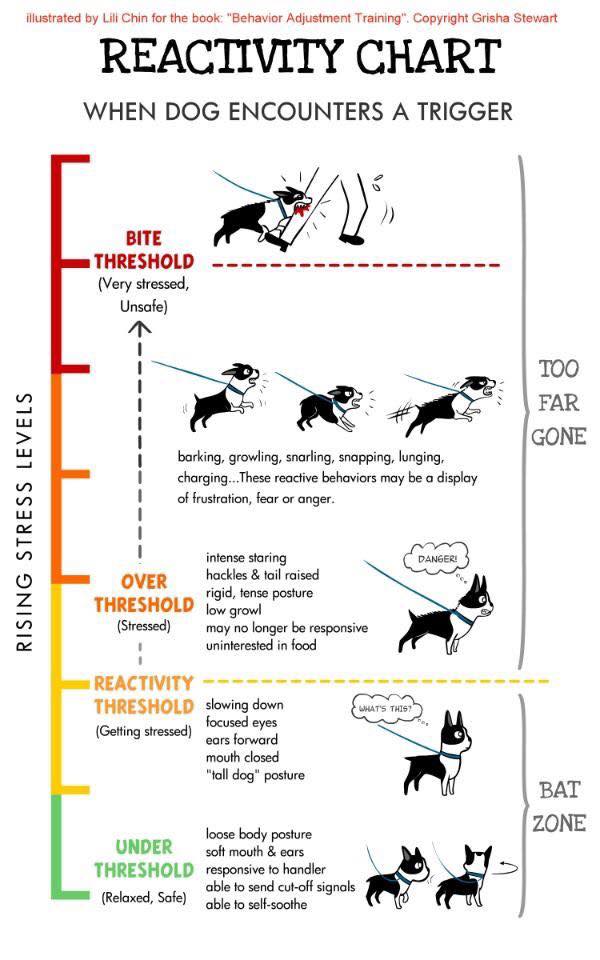

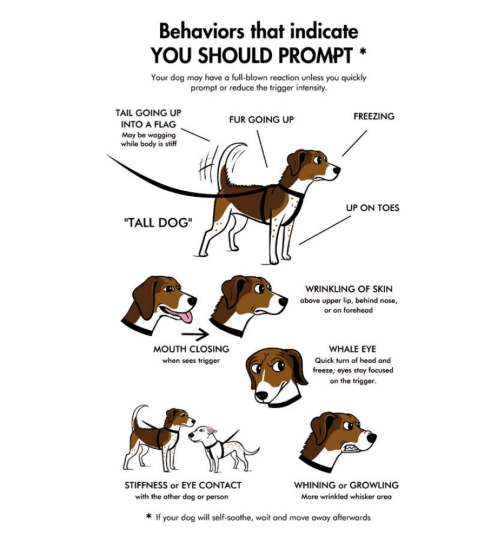

Like all things, you need to start at the most easy level. Dogs, we know, can see 400m away. Some even 900m. Plus they have a nose. They KNOW there are dogs, even if they can’t see them. That’s why you might need a behaviourist as a critical friend to help you read your dog so that you know when he’s alert but able to disengage.

You also need to make a plan. I usually use a 6-month SMART plan. That in 6 months, I expect my dog to be able to wait in the vet with 6 dogs and pay them no mind.

And then I work back from that goal. In 3 months, I think that’ll look like being in a Sports Hall sized room with one other boring dog over 50m away and pay them no mind.

In 12 weeks, that might look like being 100m away from three or four boring walking dogs when we’re outside and paying them no mind.

In 6 weeks, that might work back to being 200m away from a boring dog who’s in sight for 5 seconds and paying them no mind.

In 3 weeks, I want to be 400m away from a boring dog who’s in sight for 3 seconds and paying them no mind.

In 10 days, I want to be 600m away from a boring dog who’s in sight for 2 seconds and paying them no mind.

In 5 days, 800m from a boring dog who’s in sight for 1 second.

You can see there are lots of goals I’ve not put in there, like the length your dog will see the other dogs for, raising the excitement level and number of the dogs and so on and so on. I didn’t want to bore the pants off you with my over-zealous goal-mapping. Confession: former marathon runner. This is how I trained. Dullsville.

But be mindful of the 3Ds… Distance, duration and difficulty. When you decrease distance, make sure you decrease duration and difficulty too.

You’re going to need an irregular but fairly frequent supply of animals and you want them in view. I like to be able to control the sightlines, as you’ll see from my post about chasing stuff, so I think of that set up a lot. I’m a big fan of big box pet stores… big car parks, I can be right at the back and set up screens using parked cars if necessary. I’m also a fan of sitting outside vet surgeries at a distance if you can find that space. They have a steady stream of clientele. Groomers, doggie day cares, dog parks, people parks and shelters are also great places as long as you are far enough away and your dog is under threshold. Please get yourself a copy of Grisha Stewart’s BAT 2.0 if you haven’t already: this is essentially that.

When you have a clear plan, you need also a taught behaviour. Often, dogs start to fixate in the absence of other guidance from you.

I don’t mean “Stop that!”

That is not guidance from you. Guidance from you is a thing to do instead.

I mean a behaviour you want them to do instead. Some people play engage/disengage, or ask for a look at me! I play “Where’s the dog?” (I do this with dog-aggressive dogs too – a bit like Where’s Wally?) which is just my cute version of “Look at that!”

Lidy is a big fan of Where’s the Dog? and we do it with a U-turn as what’s reinforcing for her is to create distance between her and the dog. But if your dog’s problem is frustration, that’s not necessary. Really, you just want them to get used to dogs being about who they don’t have the right or the need to interact with – I want them to be able to walk through a dog show like I do – saying hi to if I know people but ignoring virtually everyone else.

Normally, I try and give the dog a replacement behaviour that has the same function and reinforcement. So Lidy wants space and is reinforced by security. You can’t do that with frustrated greeters. They want to decrease distance and be rewarded with a new dog friend. All I’m doing is teaching them, “sorry dude… not on lead!” or “not unless we say so!” – so what you are doing is inoculating them, little by little, against frustration. You’re using very small amounts of tolerable frustration to get them used to it.

Now some may say that this isn’t what they want for their dog. Their dog shouldn’t have to get used to frustration. They might even think that this is not “Force Free” or “Purely Positive” training. Frustration is an unpleasant state and our dogs should not have to feel it.

The trouble with this view is that it’s so massively ego-centric, and not even thinking of the dog’s welfare. Flika likes to chase cars. One day she will get biffed in the face by one and I will cry. I don’t let her chase cars. She also likes to chase cows. One day one will kick her i the head and I will cry. I don’t let her play with cows. I understand that it’s frustrating; I want her to feel as minimally frustrated as possible. But I have a responsibility to other beings, including those dogs like Lidy who find it an affront to their very being to have some great lummoxing dog race up to say hi, and to those cats, cows, horses and other creatures.

Life has its frustrations.

I do like to teach other behaviours too.

I do a “Let’s go!” as well. It’s lucky I did when Heston and Flika ran into a bunch of over-excited cani-cross dogs on Sunday.

I don’t use a clicker – just a word. Less to manage. You don’t need a clicker if you feel it’s cumbersome or if you haven’t used one before.

But the thing to remember is that practice makes perfect. Don’t expect your dog to control themselves if you haven’t trained them to. I was never so glad I’d done this stuff as the day someone brought their goat to the vet. Having the best behaved dog in the vet made me so proud, especially when I know how full on he can be. Most importantly, the goat didn’t have a dog whose intentions he had no idea about. Your dog isn’t just frustrated themselves: they make you embarrassed or upset or angry, and they turn other dogs into the Lidys of the world: over-reacting to any acknowledgement whatsoever by stabbing them in the stomach.

Set a time-table, sit down and write your goals. Plan your set-up zones, be prepared and remember, if it’s frustrating for you, it’s frustrating for your dog too. On the other hand, you don’t want to risk your dog becoming antisocial, so teach them how to greet nicely too. Jean Donaldson’s book Fight! has some excellent guidance on that. And yes, I mean on-lead greetings as well as off-lead ones. My dog needs to be versatile to cope with what life throws at them.

So don’t feel like you have nowhere to go with this, or don’t feel you need to use punishment (fastest way to turn frustration into fear and aggression). Use a harness and a long line, learn how to read your dog’s body language and keep an eye on their behaviours. Forgive yourself (and your dog) the occasional mistake or slip-up and remember that you can do it. Go back to basics and work up through your plan again. It’s boring, it’s meticulous. It’s Dullsville, but it works 100%.