Or… perhaps I would be better to say inappropriate chewing since most of us would be pretty alarmed if our dogs gave up chewing altogether. I know my dogs sometimes seem to inhale their food, but there is a small degree of mastication involved in the eating process, depending on what and how you feed. A dog that never chewed anything would be as alarming as one who chewed everything.

Like other destructive behaviours such as digging and trashing, there are many reasons why dogs chew. Why they are chewing and what they are chewing has a lot to do with how you stop it, too. This post is also about dogs who eat stuff that they really shouldn’t. I dare not tell you the disgusting things that Tilly has unearthed from the trash. But inappropriate consumption of hot kitty turds… that’s Tilly. A litter box is just a hot food buffet for that pretty little monkey.

If you’re interested in stopping your dogs chewing things they shouldn’t, or avoiding costly trips to the vet to extract an army of plastic soldiers or a kilo of pebbles, it’s important to understand why dogs do this crazy stuff.

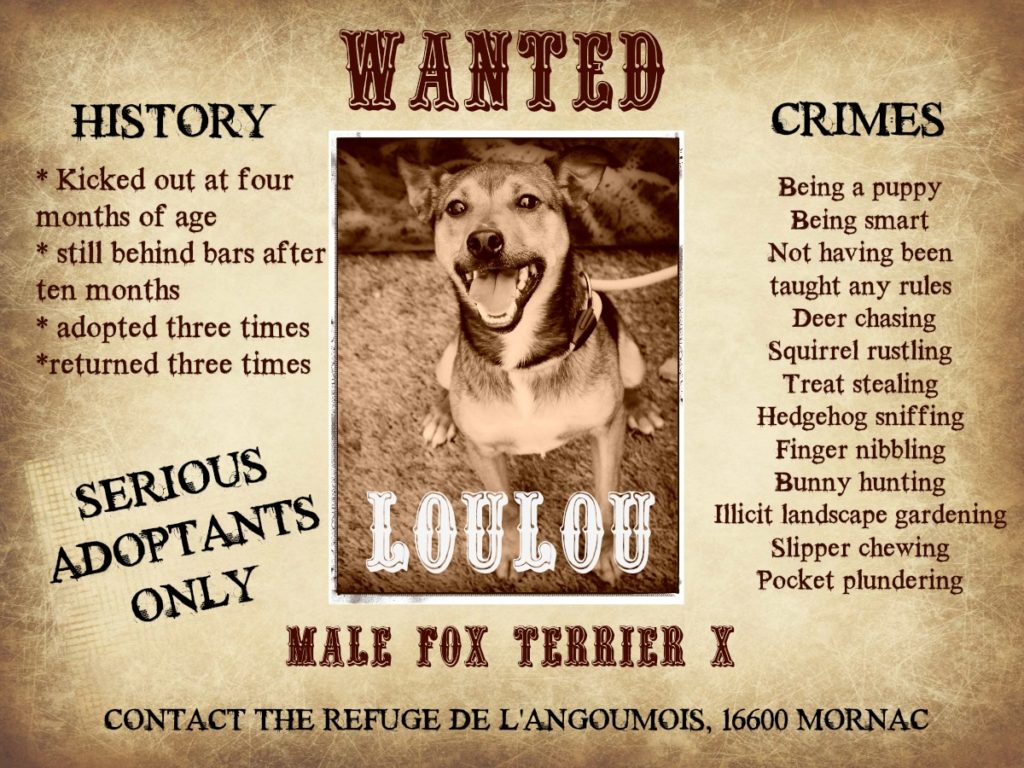

For a dog, chewing can be an age-related thing. Chewing is one way to explore the world. Where human babies want to touch and grab things, puppies want to chew it. A lot of that chewing is just pure investigation as to what is good to chew. Too hard stuff is not good to chew. Flat stuff that doesn’t have a corner or edge is not good to chew. It’s all a process of elimination to a puppy. To chew or not to chew, that is the question. At this age, many puppies can be little land sharks, running around and sinking their teeth into everything just, you know… because… well, why the hell not? They haven’t tasted your sofa cushions yet and they just might make an excellent chewtoy.

Chewing can also relieve toothache when teething, so you’ll see it when your puppy ages as well.

As your dog ages, you may find that youthful exuberance manifests in chewing. A young dog who doesn’t get enough stimulation and has too much access to the world around him will quickly work out that chewing is an effective way to while away the time. You might turn to Netflix or gaming to fill your hours, your dog might turn to chewing. For many dogs, dissection is a part of their predatory motor pattern. It’s an innate desire to shred, destroy and dismantle. For dogs with a strong desire to dissect, it’s going to be really important they have robust chews and that they do not have access to things with stuffing. Leave a terrier with a cushion and you may wonder what happened, but for dogs with strong urges to dissect, that cushion is a fabulous substitute for a small furry critter.

Chewing, like many other behaviours, is also reinforcing for a dog. It can release stress-busting endorphins too. Believe it or not, that’s also true of self-mutilating chewing. Tilly does this. She nibbles her feet compulsively. It doesn’t harm her and she can be stopped, but when she goes to bed, she nibbles her feet. I noticed her doing it when I did a video of my dogs home alone recently. A minute of self-grooming is not an issue, but for dogs like Diabolo and Lucky at the shelter, those tail-biting times have led to severe self-mutilation. It doesn’t seem logical that pain would release endorphins, but it’s as true for humans as it is for dogs. This is why you might notice your older dog starts chewing at their paws. Arthritis or old injuries can cause issues. For Gaven, who’d nibbled away a lot of his fur on one of his rear paws, an xray revealed an old fracture and some necrosis in the tissue, as well as arthritis. Antibiotics cured his chewing. Nibbling the undercarriage, tail or rear end can also be a sign of anal gland issues, particularly if your dog is a ‘scooter’, so a vet check will help rule out medical reasons for self-mutilation.

Self-mutilating chewing and another specific chewing behaviour can also be signs of psychological factors that you might need to check out. If your dog is chewing or destroying exit points when alone, you may want to explore further whether they have separation anxiety or isolation distress.

If your dog is self-mutilating, it’s really important you seek out the help of a trained behaviourist or veterinary behaviourist who can help you deal with these issues. Every programme will be adapted specifically to your dog.

Another reason your dog may be chewing is dependent on what they are chewing and whether they’re swallowing. Chewing is one thing and can be annoying or lead to damaged teeth and mouths, but swallowing is another ball game completely. Dogs are happy to self-medicate in some circumstances, and it is not unknown for dogs to develop pica. If your dog is eating turds (their own, other dogs or other animals) they could be following a happy pattern of many dogs of the past who may have survived from eating human waste – including our most personal and intimate physical waste. For females who’ve had a litter of puppies, they may find it hard to put aside their maternal instinct of cleaning up canine fecal matter. Puppies, in turn, can learn this behaviour from their mum. But if your dog is seeking out specific things to eat, like they’re mincemeat of the plasterboard, you may want to check out vitamin and mineral supplements. Parasites can also be a reason why a dog might consume things that it’s not supposed to. A vet check would be a good starting point.

Most destructive chewing when alone is not a sign of anxiety, however, but a sign of boredom and access to too much space or too many resources. If a dog is chewing when you’re present, remember that you telling them off is giving them attention. A dog doesn’t care much if your attention is positive or negative. If they chew and you say, “Ahhhhh, Nero, you bad dog!”, your dog will quickly learn that they have a magic way to get you to stop looking at the television or at your phone and look at them instead.

Once you’ve thought about why your dog is chewing, it makes it a lot easier to get them to stop. As always, rule out medical reasons first with an appointment with your vet.

For puppies, removing every single item you don’t want them to chew is vital. Managing the environment is key here. This is why pens and crates are great when you are not actively supervising your dog. By that, I mean your eyes must be on the puppy ready to intervene the moment before it starts looking at your computer wires. It also prepares them for adolescence when destructive chewing can reach epic proportions especially if you have a high-energy dog. Teaching your dog how to deal with your absence (and those ‘passive supervision’ times when you are present physically but occupied mentally) will stop them ever developing bad habits in the first place. If habits have developed already, it also stops your dog getting a fix of something that is very rewarding and reinforcing.

When you are actively supervising your dog, you can use the switch and trade method to teach them what you want them to chew. Have a range of really interesting toys in different materials and allow your puppy to decide whether it wants to chew on a chewable strip or whether it wants to suck on something softer. Making sure your dog understands what it is acceptable to chew and making sure they always have access to these things (and no access to your prized possessions) can help.

As your dog ages, it’s important to make sure they are occupied in your absence and that they have access to many chewable things. Kongs are a gift and you can make all sorts of wonderful chewable goodies that help your dog use up its chew-time wisely. At adolescence, it’s vital they don’t develop preferences for things. Counters and table tops should be clear so that your dog doesn’t learn to counter-surf to find contraband chewables. You can also help your dog out by providing lots of mental and physical stimulation, especially before absences from the home. If your dog has a strong innate desire to dissect, soft furnishings are nothing but fun substitutes for a rabbit or rat, so keep delicate toys and soft furnishings out of reach when you are absent. For power chewers, it’s going to be really important that you have a robust chew toy. Even my Ralf who could dissect a can of dog food if he felt like it didn’t manage to break a Kong Safestik. Be careful with chews and think of your dog’s teeth. Slab fractures are more common than they should be. The rule is that if it’s stronger than a tooth, it is too hard. Weight-bearing bones are not good, neither knuckle bones of bigger animals. Some soft horns may work along with softer uncooked bones, but these are things to discuss with your vet. Tendons often make good chews, where hooves and horns can be too hard for many dogs. Rawhide may seem like a good option, but often it is treated and you need to be careful about the chemicals that have been used in the process. Supervision is also important, which is why not all chews are things that a dog should be left with.

Don’t forget that if you have a persistent problem with a dog eating other dogs’ turds, or snaffling things on a walk, a muzzle can help. Muzzles are not a long-term solution but if it’s a very specific problem and a habit that is entrenched, a muzzle is certainly an option to consider, although not something that I would leave on an unsupervised dog. For a dog who self-mutilates or nibbles, see your vet and a behaviourist in tandem. For a foot or tail-nibbling habit, it’s vital you break this endorphin-producing habit and have plentiful access to more interesting chews can help stop the self-soothing and transfer it to a more appropriate chewable.

For dogs who chew or eat inappropriate things, managing their environment is crucial to preventing habits and breaking habits. Giving them lots of appropriate alternatives will help them refocus that energy. Muzzles, pens, supervision, leads and crates are your friends here. For dogs who can’t manage alone, this is especially vital. Rule out anxiety-based reasons and make sure your dog has been exercised before your absence as well as having zero access to contraband as well as bountiful access to the stuff you do want them to chew. When you’re present, a trade will help your dog understand what they should be chewing or eating.

In the next post, I’ll be looking at ways that you can deal with poor socialisation with other dogs