Fostering animals for your local shelter is one of the nicest things you can do, but it can also be one of the most challenging. I say that having had about four hours sleep with a howling cat, a whimpering lost soul of a York and one of my own who has dementia and is up and down all night.

Not that it’s all like this. Some fosters are absolute dreams and fit in immediately. Some are so easy that it’s untrue. Some will become permanent members of your household.

I don’t like to think of myself as a fosterer. If you asked me what I do, I wouldn’t place it high on my list of ways I support our shelter. That said, I’ve had almost fifty dogs and puppies through my doors in the last three years, and almost twice as many kittens. But I know there are people who are much more involved in fostering for other rescues, and I’m sure they’d have plenty of support to offer too.

You aren’t reading this because you have easy fosters. You’re reading this to be prepared if you’re thinking about it and to find some resources if you’re a regular fosterer. In the vast majority of cases, the advice that follows is for the worst-case scenario for dogs who arrive with every single problem on the planet. In reality, very few dogs are like this or need all the precautions, but it’s vital to understand how to prepare for all eventualities.

If you’re thinking of fostering, make sure that you are prepared both practically and emotionally.

The guidance below isn’t an absolute, but you may want to notify the shelter about your own situation and they can do their best to find a dog who suits your own practical situation.

It helps if you’re a couple or you have good friends who live very near. If you’re a single fosterer like me, it can be really hard if you have a dog who has separation anxiety or who needs a permanent presence. It’s no fun having to enlist dogsitters and neighbours to help out, I promise. It’s also really hard if you have to work. If you have a sleepless night for one reason or another, getting up to work is seriously no fun. If you work from home, that is much more practical, since you can be present. If your hours are flexible, that’s also a bonus, as you can catnap if you need to. Believe me, this morning I’m feeling the need for a lie-in! If you have a partner, if you don’t work full-time or you work from home, fostering is much more likely to work for you with a wider range of dogs than if you are single and if you work.

You also find you need the right sort of house. A secure garden is a must. You just don’t know if your new foster is an escape artist or not. When dogs arrive, they can be really disorientated and may try to find shelter. Although you mean well, your new foster may see you as a huge threat. If your garden is not secure, you’ll run into problems. Whilst it may seem achieveable to put them on a lead, it really isn’t a practical or perfect solution. If you don’t have access to a garden or secure space, you are going to find that the number of dogs you may be able to take to be very limited indeed. Younger dogs need the space to let off steam and older dogs’ bladders don’t function as well as they once did. Believe me, it’s little fun to get up three or four times in the night – and less so if you have to get dressed to take the dog out on the lead.

Having sympathetic neighbours is a bonus for barking issues.

If you are very houseproud or garden-proud, being a fosterer may not work for you. Dogs dig, and you may find yourself frustrated if your new foster digs up your newly-planted roses.

Wipe-clean floors and walls will make a difference too, since not all dogs will arrive housetrained. They may well have been house-trained once, but just because they know not to pee in one house doesn’t mean they feel the same about all houses, especially if you have other dogs. You’d be amazed by how high up a dog can aim, believe me. Low-hanging curtains are itching to be marked. Leather couches and metal chair legs are much better to clean than fabric sofas and wood. The more your house has dogs through, the more likely accidents are to happen, I’m afraid. If this bothers you, then you may find there are a smaller number of fosters available coming in from surrenders and are ‘guaranteed’ house-trained. However, with any change in environment, there can be upsets.

If you have a house with stairs or you live in an apartment that is up a flight of stairs, this may also pose problems for dogs. Not all dogs know about stairs, and stairs can be very scary. If you foster youngsters of large breeds or oldies, stairs may not be possible at all. Steps can pose a similar problem. You may find that dogs don’t cope well when they are in one part of the building and they can hear you in another. Although this is something that dogs can learn to cope with, it is not so easy to teach them when they are with you for an indefinite period.

Having indoor doors is also helpful, especially if you have dogs yourself. A makeshift X-pen or puppy pen may help, but not if you foster St Bernards. Remember too that doors pose no obstacle for some dogs, like Flika who is here with me now. Luckily, she is not an escape artist, but having bolts and hooks can also help. Secure, lockable gates can help as well. There will be times you will need to separate your animals or when you will need to have a safe space if your foster dog is upset by arrivals and departures.

Think too about the handles on your doors if you have an escape artist or a jumper. Some handles can be sadly too easy for collars to get hooked on and I’ve known a number of dogs strangled this way. A breakaway collar with your number on it is vital, as is a microchip. Newly found dogs are more likely to be disorientated and wander off, so it’s helpful that people know how to get hold of you. All my fosters get a breakaway collar (which will release if snagged) and have my number on their collar (hoping they don’t lose it!) because if they do get out, your neighbours might not necessarily realise that the dog is staying with you.

If you have a dog who escapes, you may also need good kit to walk them (and maybe to leave on for 48 hours or so). I like the Ruffwear Webmaster harnesses for this, but they are expensive and you can’t always get one quickly. The six buckles and long bodice make it practically inescapable. Greyhound and whippet harnesses may also work. Put a lead on the collar and a lead on the harness and secure both with a carabiner if they pull. Nothing can be worse than a scared foster doing a runner. Do away with walks for a week if you are worried about this. You may also need a special, secure harness if you are fostering a dog-aggressive or person-aggressive dog, as well as a muzzle and the skill on how to train them to wear it. It goes without saying that my foster dogs don’t go off the lead – ever. Not even if I think they won’t toddle off. It doesn’t matter if they are well-balanced and follow you everywhere.

In the home, make sure you have a safe place to contain your dogs away from each other when they are unsupervised. This week brings yet another sad tale of a bigger dog killing a smaller one. 10kg is a big enough difference that a fight can end tragically, and whether it’s a case of predatory drift, where a larger dog attacks a smaller dog, or something completely different, it’s vital you can keep your biggies and your littlies apart. That is especially true in the garden.

Two of my fosters. Effel the Beauceron had some predatory drift, chased small things and nipped. No way I was letting him out in the garden at the same time as Dougie the Minpin. Sadly, Dougie had very severe separation anxiety and since a crate couldn’t contain him, it was not possible for him to stay longer than the few days he did. Sometimes, being a fosterer means admitting that there are problems you aren’t equipped to deal with. Don’t ever take your own dogs’ behaviour as an absolute. My old mali dude Tobby was the most dog-friendly non-aggressive dog there could be, and he still got a case of the chases with a young hound I had here to stay. Not so big a problem when the young hound could easily outrun an ancient old rickety arthritic malinois, but the last thing I wanted was a full-force, full-health 50kg beauceron catching a 4kg minpin.

Flika also has separation anxiety like Dougie did, but she is bigger, it’s less of a problem to leave her unsupervised with my other dogs. But know that it’s not the best of ideas to take a foster if you can’t guarantee they can be supervised a lot of the time. Being inside and dry is not the only reason to take them out of a shelter if they’ve got to spend 10 hours alone whilst you’re at work.

You also have to think about food times and sleep. It’s best to have a range of beds and not to take a dog if your own dogs have resource guarding issues that you can’t manage. Whilst your own dogs may steer clear of your grumpy cocker, your foster dogs have no idea that they’ll unleash seven circles of Hell if they so much as look at your dog. I usually feed fosters separately, and I put their food down first, because my dogs are well-trained and know how to wait. Don’t feed your foster last in some misguided ‘pack rank’ sequence as if they haven’t been trained to have manners around other dogs eating, you may unleash a very nasty fight. When I feel like my fosters are ready to join the ranks, I give them more (sometimes packed out with cooked vegetables) so that I know they aren’t going to finish first and go touring about the other dogs checking out their bowls as they finish. You’ll forget this from time to time – but with a semi-blind foster, a deaf dog, a grumpy cocker of my own who eats slowly and guards her food, a tiny York and a dog of my own who outweighs him ten times, I really don’t want the mother of all scraps in the kitchen.

Get more beds than you can possibly think you need and make sure you’re prepared for a little upheaval at night. The older the dog, the more likely they’ll have quite intractable sleeping patterns that you might need to live with for a while. You might not always know those sleeping patterns, but if they seem agitated at night, you can be sure you’ve not got it quite right. The way Dougie dived on the bed and wriggled down underneath the covers told me everything I needed to know about where he’d been sleeping – or, at least – where he preferred to sleep. I have to be honest, it’s one reason I like the oldies and the biggies – they usually are happy with a basket. Few people have giant dogs sleeping in their bed, and in general, you can go off breed in some way to help you decide. Don’t be surprised if your beagle foster is not used to being indoors, if your husky is hankering for the garden and if your minpin foster sneaks under the covers. I’d say to keep with the rules you intend to follow up on (no couches, no bedroom) or those that will make the dog adoptable (being crate-trained, sleeping quietly alone in the kitchen) but in reality, those first nights for a dog can be so unsettling that now is not the time to get into teaching plans about how you want the dog to be able to sleep. You are a vital stepping stone but there’s no point starting a crate-training programme if you don’t know you don’t have weeks to work it through.

For behavioural problems, you’re managing a triage station. That’s to say you’re there to assess and to manage rather than to treat. Whilst there will be many things that you might be able to teach, you have no idea if the dog will be with you for three days, three weeks or three months, so starting on a programme that may not suit their permanent owner is pointless. My aims are to keep distress to a minimum, not to teach the dog how to fit into my household.

You ask yourself three things: Can I manage the environment to prevent the behaviour? Can I quickly and effectively teach a different behaviour? Is this too big a problem for me to deal with and the dog needs to go to another foster home?

Sometimes you can manage. Sometimes you can treat. Sometimes it needs more help than you can physically provide. Knowing when to manage, when to intervene and when you need to pass is vital.

I think that’s the most important message about the practicalities of fostering: you have to be adaptable, flexible and ready to react. You have to fit around the dog, rather than help the dog adapt to you. Most dogs fit into your patterns very easily, but some will not. If it’s really clear that the dog needs more than you can offer, it’s vital that you get in touch with the rescue that you’re fostering for. It doesn’t preclude the dog from being fostered elsewhere or finding a home. Just because you can’t be there 24/7 for a dog with separation anxiety doesn’t mean the rescue won’t have homes where there is always someone in, or a neighbour to visit. Neither does it mean they won’t find a home. Forewarned is forearmed.

Hygiene is also a practicality I’m going to mention, because it is important. Vaccination of your own dogs is going to be important, but know that if your dog is coming from the pound, you need to be aware of things like kennel cough, dog gastro, giardia, conjunctivitis, canine influenza, skin mites, ear mites, leptospirosis and so on. These are not usually anything that would be a problem – it’s like the risk you take if you run a guest house. But… if you have sick, old or immunosuppressed dogs, you need to make it clear that you can only take surrenders or ones that have had a very thorough health check. If you have a dog with severe flea allergies, you need to make sure your new arrival is treated before they arrive. Keep up to date with wormer treatments, as tapeworm eggs are spread by fleas. Other things that are contagious and can be problematic include mange, ringworm and ear mites. You won’t even think of these things until they matter. One dog through with ear mites, could mean one ear infection for one of your own oldies, one vestibular attack and you’re severely risking the health of your own pets. A thorough check-up is more than enough, and if your dogs are young and robust, you will probably find that things pass them by. But if you have an oldie or a dog who is sick, it may be time to have a rest for a bit. Bear in mind that the risk of these is slightly higher if they have come from ill-kept pounds or have lived in communal conditions, but for a dog who has come from a clean pound or has been in isolation, the risk is no more than it would be in any social setting. If your dogs are healthy, infection may pass them by, but please check with your vet.

The emotional impact of fostering can be hard. You need to be aware of compassion fatigue. I was certainly aware of it this morning between the screaming cat and the whining dog! Sometimes you say yes when you should say no. The longer you have been fostering, the more likely it is you’ll get tired. Turnover is exhausting, for both you and your own pets. Sometimes you need a break, and that is absolutely essential. I needed a break when Effel went – I’d had almost two years of continuous fostering, with numbers ranging from between 4 dogs to 16 dogs. Sometimes it is just too much and you need to have a way to say so. Even if the dogs are really well-behaved, you need to have times when you can say no. The sheer number of kittens I’d had through was just emotionally and physically exhausting. There are times when you feel absolute despair about the way society treats its animals. I don’t need to tell you that I feel a bit like that at the moment, with an exhausted, aged Yorkshire terrier here, and a half-blind, wobbly old ex-guard dog who arrived with cystitis and no doubt had a stroke of some kind at the shelter. Doing it all the time is exhausting, even if it’s all you do. The adoptions and post-adoption stories will remind you often of the good you are doing, but it’s not always enough when you feel like you are fighting a rising tide.

You also need to be aware of the spectrum of emotions you’ll have for your foster. There will be some you will be attached to with your whole heart, who you will wish you could keep. I loved Effel, but it wasn’t practical to keep him. He and one of my own dogs didn’t get on particularly, and neither was truly happy. But I tortured myself over it. When they are easy, you may find yourself advertising them less or being less of a participant in moving them on, but that can have long-term implications for dogs who are then uprooted to go and live in another new home. When they are ‘tough’ adoptions, you may also find yourself feeling guilty for needing them to find their home, especially if they have had a tough life or if they are bonded to you. Sometimes your dogs will fall in love with them and you won’t!

Other times the foster may be really hard and you will be really glad to see them move on. Despite your feelings, you’ve got to be honest about their behaviour. Glossing over it to find them a home will only end up as a failed adoption and the dog possibly being returned. One of my fosters was a barker. Another had springs for legs. One played horribly with my own dog and had to be kept separate most of the time. For problems like these, you may find yourself needing to be honest about whether you can manage it, whether you can treat it or whether the dog requires a different foster home. Don’t feel guilty about those times you’ve felt relief that the dog has found a home.

To be successful at fostering, having a mentor to help can really help. Having someone there to help you through with the common niggles is important… what to do when they don’t eat, when they’re a bit unwell, when they won’t settle, when they’re not house-trained, when they bark for attention…

Being in regular contact with the shelter or rescue is vital too. You can neither be a primadonna nor a pushover. There are times you’ve got to say: “this animal needs a vet, now!” and know it will be taken seriously. You’ve also got to know their protocols and systems. Having a timeline in place is helpful too – in case you need to go on holiday, if you are needed for other activities. This is also useful in case the animal just doesn’t move on or find a home. You’ve got to know how long it is that you would be prepared to foster for. And you need to know who to ask to settle a bill, to cough up for washing powder or specialist food if necessary.

You’ll have to help out with advertising, too. The best fosterers are ones who make a concerted effort to keep photos, videos and information up to date. A dog who is not advertised and regularly updated is a dog who will be with you a long time. Nobody cares if your photos are poor – what matters is that there are lots of them. It matters too that dogs are accurately described.

What will also help is a basic understanding of the animal’s needs too. If you have puppies, a knowledge of canine development is essential. What point is there in ‘housing’ puppies only to turn out dogs who haven’t had the best start in life? It’s not enough to say ‘well, it’s better than they’d get in the shelter.’

Likewise with geriatric dogs. Having a good knowledge of how to cope with declining sight, hearing and bladder control is vital, but it’s also useful to know a bit about various degenerative conditions so you can keep an eye out for them. Having an understanding beyond ‘well, I had an old dog once’ is vital to understand a geriatric dog’s needs.

There are plenty of other things you will benefit from being a bit interested in: nutrition, health, development, life cycles, behaviour. You are in the scary position of acting as a surrogate shelter. Sometimes a dogsitter is more than enough (and there have been times when that is what I have been!) but there are also times when you need to know more than the average person about canine behaviour, training and health if you want to be able to take on more challenging cases. Some dogs are going to need nothing more than a roof over their heads, a bowl of food and a walk now and again. Some will need more than that.

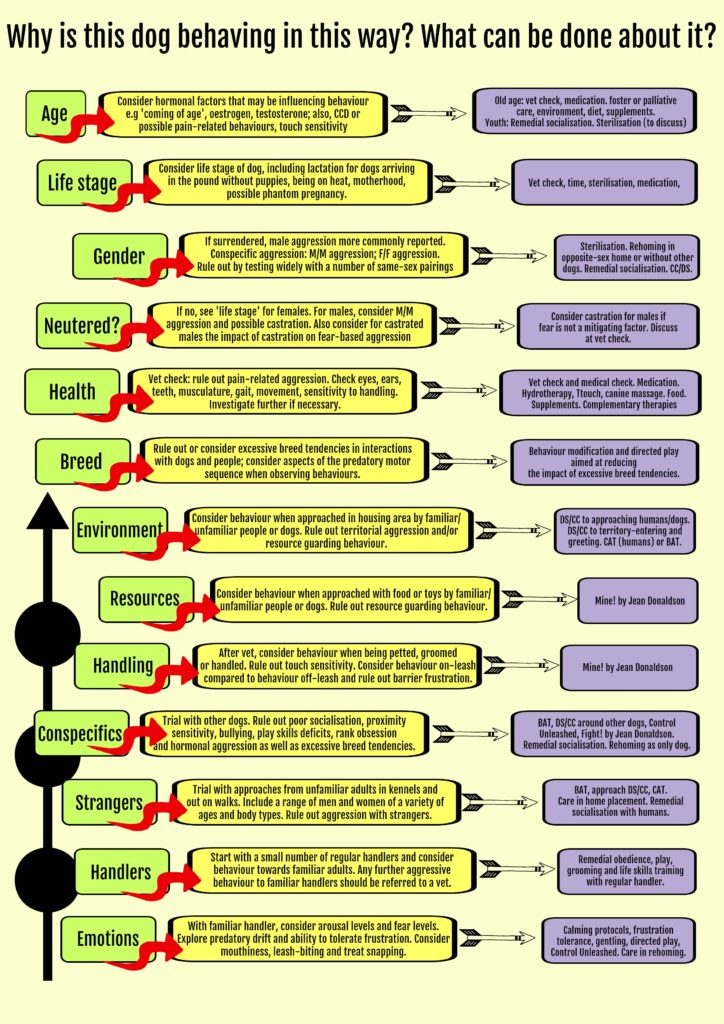

What follows are links to some other articles that you may find helpful. They are written for adopters but work equally well for fosters. For those tackling a behaviour, look for the ‘environmental management’ tips too.

- Kitten fostering

- Introducing a new dog

- The first few days

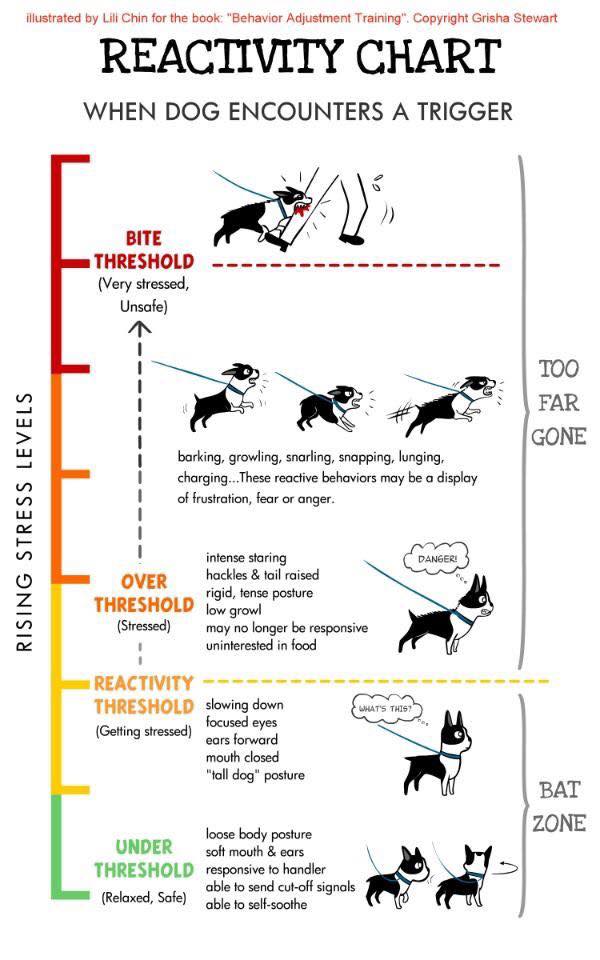

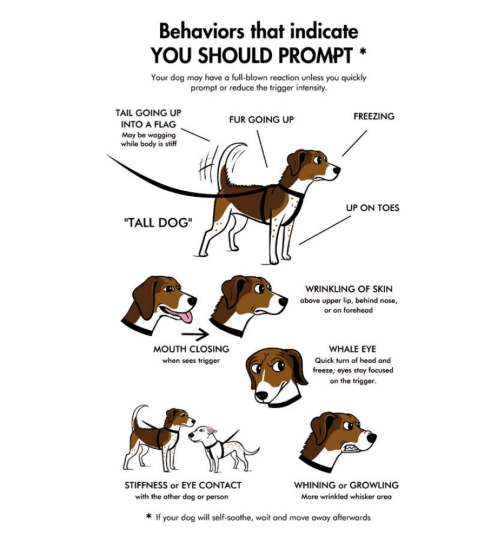

- Trigger stacking

- Introducing new dogs

- Introducing dogs and cats

- Dog proofing your home

- Puppies

- Fearful dogs

- Resource Guarding

- Advertising shelter animals

- How to take good photos of your foster dog

- How to manage a multi-dog household

Problem behaviours: