Mounting and masturbation… two words guaranteed to raise an embarrassed smile if you’ve got a humper. It’s a behaviour that can be completely innocuous and infrequent, or a behaviour that can cause an awful number of potential dog fights if you’ve got a dog who thinks that humping is an acceptable way to meet a new dog.

And you may be wondering about the two dogs above, who look like butter wouldn’t melt. The first is a doddery old deaf poodle with a heart condition and cataracts called Cachou. The second is a doddery old beagle cross with health issues of his own. Both of them have a dirty little secret… they love a bit of humping.

Humping is a behaviour that’s rewarding in itself. But why do dogs do it?

The reasons are often complex. Some call it a ‘fixed action pattern’, or FAP for short. Sorry, if you’re down with Internet slang, and I apologise in advance if you are not and I’ve now taught you a new word. It seems kind of appropriate that humping and masturbation would come under (sorry, again, for the inadvertent innuendo that is likely to pepper this piece) an acronym that represents the sound of masturbation. A fixed action pattern is a hard-wired, instinctive behaviour. In other words, your dog doesn’t need to learn to learn to fap, hump, masturbate or spank the old monkey: it’s one of those behaviours they just ‘know’. And once it’s reinforced, it’s a behaviour you’re likely to see again and again.

That’s to say, if it feels nice, they’re going to do it again and again. And the more they do it, the harder it is to stop.

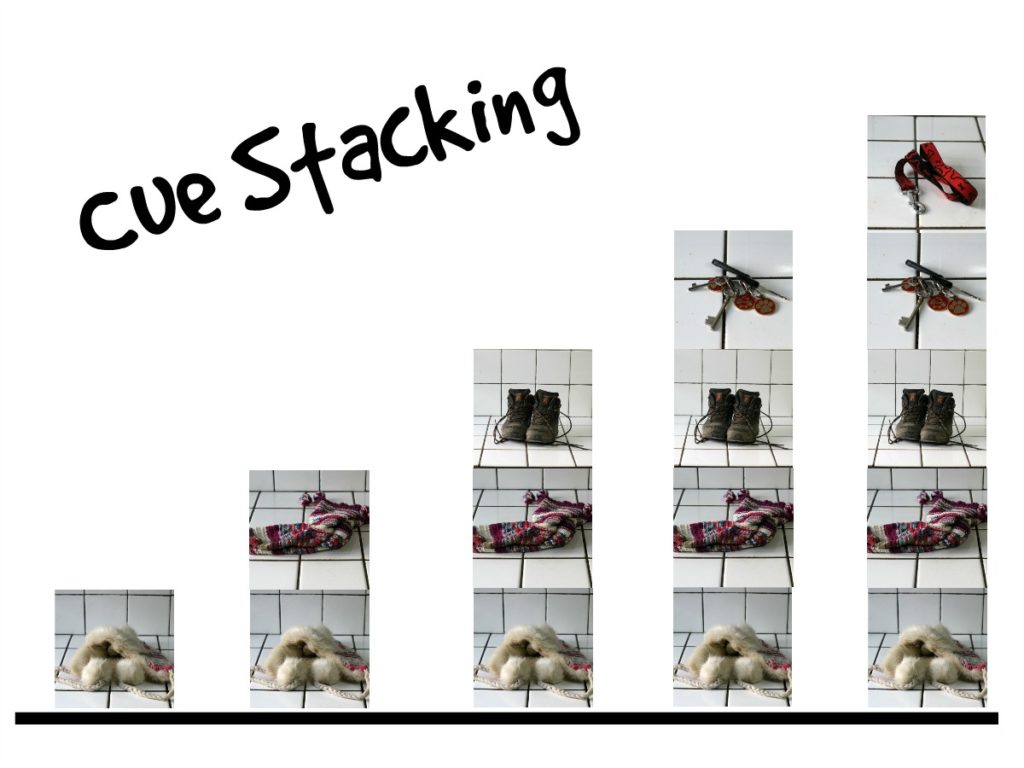

Some humping is part of play as dogs age. Boys hump boys. Girls hump girls. Boys hump girls and girls hump boys. So my dog Heston has been humped by his brother Charlton. Tilly was humped by her older friend Saffy. Heston humped the lovely Galaxy. And Hista humped Heston. Girls who like boys who like boys who like girls… Humping happens. Often it happens when dogs are excited or anxious, and I’ve seen dogs hump during introductions or the first couple of hours of play. Greetings are exciting and also create a lot of social anxiety. Excitement or anxiety both mean your dog is aroused. Arousal gets to the parts that other emotions don’t reach. Saffy used to hump Tilly before we went for a walk. Heston humped Galaxy when their play burst out from chasing and running.

Humping can be a sexual thing, of course. If you’ve got intact males around females in season, you might be used to a little self-pleasuring if they can’t get near to each other. Tobby, my old Mali, was always super-excited around unsterilised females, even if they weren’t in heat. He’d even air-hump if he couldn’t get to the girls, poor old dude. Some people think young dogs do it because they’re learning for future encounters. A lot of young dogs start doing it as they come to sexual maturity or even in play in preparation for that moment.

Humping can also be a positional thing too between dogs. I’ve seen intact males driven nuts (sorry!) by castrated males, and older intact males humping younger intact males. There’s no evidence dogs do this for status around humans though, and to be honest, I’m not sure what it means about any rank issues, and it is our human fallacy to read stuff into humping related to rank. Virtually every single time someone’s told me it’s about status or rank, it’s been excitement/arousal or social anxiety, and that’s as true for other interactive animals that dogs hump as it is for their relationship with other dogs. Dogs hump humans, but they hump cats too, and they will hump inanimate objects, often as a kind of surrogate.

Sometimes it’s just at greeting. I put this down to social excitement and anxiety. My old boy Ralf humped Heston when he arrived here. He never did it again after that. Tobby tried endlessly to hump Tilly when they met, but she never put up with his humpy ways. It’s no wonder she’s so fear-aggressive in new meetings with dogs. Her milkshake still brings all the boys to the yard (sterilised as she is) and who wants humpy boys in your face when you’re a demure older lady such as she is? She’ll accept other flirtatious behaviour, but no 11kg 11 year old sterilised cocker wants an ancient and arthritic 25kg malinois humping away at her.

I suspect sometimes that dogs smell hormonal or medical changes in other dogs… hence the occasional humping of young males in their prime by doddery old dogs. They never, ever humped each other and it was completely out of the blue at a time with no other arousal. Tilly, although sterilised, certainly has times when she smells good to the boys, and I’ll find Heston sticking a paw over her and pulling her in when he never shows interest at other times. Four days before Ralf died, Heston humped him. I never saw him do anything like that at any other time, but I suspect Heston sensed something that I couldn’t. As Tobby’s degenerative neurological condition worsened, he would often become aroused too – so humping can be a sign of something medical with either the humper or the humpee. If your dog suddenly starts humping more than they did before, or becomes a target for humping, it’s worth a vet check. There are medical reasons for humping, and it’s important to rule them out first, especially if the dog is known to you and there are changes in the frequency. Urinary issues, neurological issues and skin allergies can all be reasons a dog might really, really want to scratch that particular itch. We so often like to say it’s a psychological behaviour when it isn’t always.

Humping can have sexual origins, play origins, social origins or even be a response to stress or excitement then.

In short, it feels good. If the object of the humping doesn’t mind, they’ll do it again. And again. And even if the object of their humping does mind, well, it might be worth a shot anyway. Humping feels nice.

Not only that, we humans often giggle when our dog humps. Sometimes it gives us a right old laugh. If our dogs realise that we are giving it attention (either by laughing or by punishing – attention is attention whatever form it comes in) a dog can happily use it as a way to get a reaction from you. A dog being told off for humping is getting the same attention as a dog being laughed at for humping. Very often, dogs are rewarded intensely the first time they do it, either by their own feelings or the reaction/interaction they got, and that ‘jackpot’ learning experience is one they seek to emulate over and over.

So when does it become a problem we need to deal with?

Sometimes, despite our giggling and our blushes, it can be fairly innocuous between consenting dogs during play.

Heston seemed not even to notice the day he was humped by a fourteen-year-old arthritic, deaf miniature poodle with a heart condition. He just stood there, unbothered, while Cachou did his thing. He didn’t even look like he realised that he had a humping poodle behind him. It didn’t need me to intervene because Heston wasn’t bothered and Cachou, well, when you’re a poodle with a heart condition, you get your kicks where you can. Heston was perfectly able to walk off if he no longer wanted to consent. When Heston humped Galaxy, they were both having such an enormously fun time that it wasn’t going to spill over into aggression. In fact, she turned around and humped him.

That said, I will usually intervene if a dog of mine starts humping. It’s often a sign of over-arousal and it can end badly if one dog is unable to stop doing it. I’ve seen a lot of play spill over from humping, as well as dogs who are humping for a psychological ‘fix’. Two dogs at the shelter, Maestro and Mogano, humped each other fairly mercilessly for a few days. There was no fighting, there was a lot of reversal and the behaviour died out, so it wasn’t a time to intervene. That said, when Maestro met his new lady friend, I went out of my way to stop it starting…. it was all social anxieties and over-excitement, and it can really sour a relationship between adult dogs from the beginning, so I usually am very keen to make sure new arrivals don’t fall into the habit. I tend to think that if dogs never do it with each other, they don’t think to do it, and it can be a hard habit to break.

That ability to intervene is key here: if your dog cannot be stopped from humping, be it a leg, a cushion, a human, a cat or another dog, then it runs the risk of becoming a compulsion. If you can’t distract your dog and their recall disappears, then it’s time to intervene. If your dog isn’t noticing the distress of the human or the other animal they’re humping, then it’s also time to intervene.

So what can you do if you have a humper and you are worried about the humping?

First, get a second opinion about whether the humping is normal or not. Like I said, it’s part of a dog’s natural repertoire of behaviours, so a little from time to time is not anything I’d be concerned about either in multi-dog packs or with a surrogate. I’d also want to know about the object of the humping: an older dog being targeted, or one who is unwell is unlikely to find the humping fun. I am usually keen to stop humping of humans simply because we find it socially unacceptable despite embarrassed laughter, and it can point to underlying issues with arousal around a target human. You also need to think about the emotional function the humping is filling: a dog who craves attention and humps for this reason will need a different treatment plan than a dog who is humping at greetings with unfamiliar dogs. If you don’t address the underlying emotional need that humping fills, then you are unlikely to succeed long-term with any behavioural change.

One of the first things to do is manage the environment. If your dog has a favourite toy that they hump, only let them have it when supervised and when you can easily remove it (being mindful that if you take it away, you could see the emergence of some resource-guarding behaviour). But if your dog is over-aroused by other dogs, keep them on a leash. If your dog humps guests, put them in their crate or in another room when the guests are there so they can’t practise. If they’re targeting a specific individual in the house, this is an option as well whilst they break the habit. When taking a particularly prickly foster, it was vital Heston didn’t hump her and so I put him on a long umbilical line for 24 hours until they’d sussed each other out. Be mindful, though, that time outs as a punisher for humping can be very frustrating for your dog and you absolutely need something in place to divert that frustration. I’ve seen dogs get full-on obsessions through being removed, and the moment the control is ended (ie you put them back in the room with the target or you take their lead off), the humping is back with an absolute vengeance.

When a lady phoned me a couple of weeks ago about a new rescue who was humping the resident dog, I advised her to keep him on an umbilical leash connected to her for a couple of days, to make sure he was kept calm and that he was given plenty of mental stimulation. It’s always a good idea to manage a known humper’s interactions with other dogs so that they are prevented from humping in the first place. If the humping is happening because of social anxiety or the stress of a new environment, nipping the behaviour in the bud and preventing it from re-occurring is vital. Separate rooms or crates for humpers and their unhappy humpees, please, until you are absolutely sure you can leave them without any humping. As a new behaviour, it is easier to use environmental management to prevent this becoming a habit. At the same time, it is vital to have an output for that behaviour.

If you manage a humper’s environment, it’s worth bearing in mind that you are disrupting a behaviour to let off ‘arousal’ steam and that over-stimulation can present in other ways through displacement activities such as digging, barking, chewing or rubbing on other things. In order to avoid that, plenty of mental occupation is vital. Stuffed Kongs, fallow antlers, marrow bones, nosework and games that require your dog to work out puzzles can really help them burn off some mental energy. Think of it as spending a little time doing a crossword rather than getting giddy over a little light stimulation of the pleasure parts. Don’t forget that if you catch your dog in the act with a surrogate object such as a bit of soft furnishing or a toy, it could well be boredom, so it’s definitely worthwhile putting some more varied activities into your dog’s life. Video is useful if the dog is humping humans or surrogate objects. If they don’t hump on their own, you can rule out boredom. In this case, if they are only humping in company, it could be social anxiety or even a bit of a learned performance, especially if they don’t hump on their own. In this case, stopping rewarding the behaviour and managing the dog around people and/or dogs will be crucial.

If your dog humps new dogs at greeting, keeping them on a leash until their initial excitement burst can work, but it can also be frustrating for the dog and lead to barrier aggression over the leash. Far better to contact an expert who’ll help you work out those behavioural quirks without causing Fido to get frustrated. Tarzans need a bit of help to meet other animals, and it is one time I am most concerned about inter-dog humping. It can so easily spill over into a fight between unfamiliar dogs, or also grow into an obsession.

What you’re aiming for is the extinction of the behaviour. Since the behaviour is rewarding in itself (you don’t have to offer a dog a biscuit to get it to hump!) then the best way to do this is to interrupt the reward and make sure they never get the pleasue from humping. That means no pleasure from your reaction (either positive or negative) At the same time, once you’ve interrupted the humping, you want to ask for an alternative behaviour (anything will do, even if it’s just sit-stay-focus!) and reward that instead. Since humping happens often at times of over-stimulation and over-arousal, you’ve got to ask yourself whether it is better to do something to allow that arousal to manifest naturally (like playing a few games of tug) or whether in actual fact you’d be better to go for some calm behaviours. Personally, I prefer the calm behaviours. I think giving the dog plenty of appropriate mental and physical activity and building in periods of calm is vital. Often, we don’t teach dogs what to do when they’re not doing anything really. Sleep is all fine and good, and dogs need a lot more sleep than we do, but sometimes humping is just self-employment because a dog hasn’t been taught how to occupy themselves and they can’t settle. A behaviourist will be vital to help you set up a good plan to work towards extinction.

Reward cessation is also important if your dog is humping a person. When I got humped by Jack, I didn’t stand there politely and wait until he’d finished… I turned around, asked him to sit and rewarded the sit. Stop the behaviour by moving away. Laughing, smiling or telling the dog off… it’s all attention and it’s all a reward.

Disruption and refocusing can also work. These work if you have got a rock-solid recall and a rock-solid behaviour to ask for instead. Even if your dog’s recall is poor, a squeaker can be enough of a distraction. What you want to be really, really careful about is that your dog doesn’t think this is also worth humping for… the humping becomes a way to get YOU to get the squeaky toys out! Here, I’d be waiting for ‘the look’ – the behaviour preceding the humping. You know, where your dog gets that goofy face or starts playing about. To do this, you need to know your dog pretty well and be able to anticipate it. When Heston starts getting a bit too interested in Tilly, I call him away. No humping. Then I ask him to do something else. No lightbulb goes on in his head to say ‘I must do X to make her do Y’. But I can see it coming. I know very well when he’s going to do it. The earlier you intervene, the more chance you have of stopping the humping happening. What I absolutely do not want to happen with distraction is that the dog starts humping because they see their behaviour as a cue for a better distraction. If I only got out the squeaky toy when the humping started, Heston would very quickly learn that he needs to hump to get the toy. The toy or game must come first (which is why you need to recognise when the humping will happen) and must be used so frequently in a range of situations that the dog doesn’t pair the two events of humping = toy. Again, a behaviourist can explain a protocol for this better than I can here so that it doesn’t backfire with your specific dog.

Some people are no doubt going to recommend spaying and neutering if your dog is not already. That’s something to discuss with your vet. However, if you expect neutering your dog to stop it from humping, then neutering may not work on its own anyway. If your dog cannot be distracted easily from a humping situation, then the pleasure is already largely psychological rather than physical and it’ll need more than a physical approach to stop it. Early neutering is not the answer you are looking for. It’s still worth a vet check. Of course humping is a sexual behaviour: there’s a reason dogs will hump surrogates if another dog is in season around them, but unless it’s JUST a sexual behaviour, it’s unlikely neutering will make a difference. Like I said, my most prolific humpers was Saffy, and her target was Tilly, two spayed females.

And if you are in any doubt at all that your requests or attempts to intervene might end badly, contact a professional immediately to help you out. This is definitely not a behaviour to leave if there is an element of compulsion or habit: humpers rarely grow out of it, especially if they are a little nervous and socially awkward.

Next week, poor house-training and elimination in the home.